The poet’s eye, in a fine frenzy rolling,

Doth glance from heaven to earth, from earth to heaven;

And as imagination bodies forth

The forms of things unknown, the poet’s pen

Turns them to shapes, and gives to airy nothing

A local habitation and a name.

Don’t be fooled, the quote above may have a likeness to Malazan, in theme, but is not written by Erikson. It’s Shakespeare. Now, beside the brashness of putting these names together, I have a point. I mentioned in the blog that I’m reading “The Wayward Mind” by Guy Claxton, and it works like a handy manual to the Malazan world. That quote from Shakespeare also comes from this book, exploring the mystery of unconscious along the centuries, in philosophy, science and literature. This has been a key to Erikson’s series and its mythological forms I’ve held long before reading Claxton or Midnight Tides. “The forms of things unknown” is at the same time defining possible mythology, as well the hidden things that lurk in the darkness of the human soul. What stands well lit on the page, defined by consciousness, and what lies deeper, unseen. The outward, “explicit” projection of that darkness within is essentially the theme of human unconscious, as well the manifestation of a mythological world where gods are very real. That’s why I see “Midnight Tides”, the title of the book, as a suggestion to what hides below, a force unseen, lingering just below the calm level of consciousness. I’m not even sure I interpret this correctly, as I can’t grasp the whole of it, or what Erikson intended. In the past I’ve been right as much as I’ve been wrong. Yet this theme is powerful through the whole book, so I’m sure there’s at least some truth in the ways I intuitively see it. In particular there’s a page, right at the beginning of the book, but coming after the Prologue, so as part of the specific story and not of the larger arc, that is extremely evocative and hard to pinpoint (I quote only a fragment but all of it needs to be read). Making it fit perfectly with Claxton’s description of symbolic language as used by the Romantics and Shakespeare before them, the “multiple layers of resonance beyond explicit comprehension” and the “hint at buried complexities”.

Between the swish of the tides, we will speak of one such giant. Because the tale hides within his own.

The theme echoes through the rest of the book but it is especially strong in one of the last pages:

For such was the rhythm of these particular tides. Now, with the coming of night, when the shadows drew long, and what remained of the world turned away.

For that is what the Tiste Edur believe, is it not? Until midnight, all is turned away, silent and motionless. Awaiting the last tide.

And finally in the Epilogue:

And it is this moment, my friends,

When you must look away,

As the world unfurls anew

In shapes announced both bright

And sordid, in dark and light

And the sprawl of all existence

That lies between.

This lingering, shifty theme runs like an undercurrent, a midnight tide proper, since what “surfaces”, with light (attention) shining brightly on it is the central plot about the Lether empire, ever expanding, and on the move to conquer the Tiste Edur tribes in the North of the continent. An avid empire founded on the myths of money, progress as destiny, and dominance as an intrinsic vocation. Versus less “civilized” tribes that have still not resolved their relationship with their past history, bound to a more static and ancient vision of the world and way of living. One could very easily read this like a direct metaphor of modern times and western capitalism, but Erikson has clearly pointed out that he was more interested in catching the wider form of it, and its constant repetition through the whole of human history (he says: “one thing Midnight Tides taught me was that once a certain system of human behavior become entrenched, it acquires a power and will of its own, against which no single individual stands a chance”). So already two levels embedded in the whole arc of the book, to which another is added: the characters themselves, and especially two sets of three brothers. The Sengar and the Beddict, representing the two sides, the Edur and the Letherii. Each of these brothers quite different from the other, providing a different viewpoint. Six mirrors carefully placed to reflect each other and the world around, so let the game of light and shadows begin…

I won’t even try to attempt a careful analysis because it’s beyond my skill and what I’m supposed to do with a review. I’m just proceeding in general terms. This book is the fifth in a series of ten, whoever may read this review will likely know what it is about and maybe it’s more interesting for me to say of my personal reaction to it, and how it fits in the larger context of the series. I’ve said before that I considered each volume better than the previous, up to the fourth one, that I liked the most for a number of reasons. I know that Midnight Tides is ambivalent for many readers, either being the favorite or way down the scale of preference. This is mostly because the context of the story is momentarily separated from the rest. It’s set on a secluded continent away from the rest of the story of the previous four volumes and with an almost completely new set of characters. A relatively blank state that carries the obvious risks. The familiar characters and context abandoned to “linger” on something new, and so having to win once again the attention and willingness of the readers. In my personal ladder of preference I’d decidedly put MT behind the previous three volumes, and only above Gardens (the first). But not because of lack of familiarity or unease with new characters and stories.

My problem and criticism sits mostly in the execution. I’ve only admiration for how Erikson sets things up and the power of his vision at all the levels he engages with. What instead I found lacking and not quite fulfilling its task in this book is what goes on page by page. Something not quite reaching in the writing and execution of the single scenes. I’m not pretending to know better, but it is simply my reaction to the book, limited as it is. I found a certain legitimacy to the criticism leveled at Erikson, in particular about the characters. The problem is not that Erikson can’t do good characterization, but I believe he was here too brazen in the way these characters are made into “devices”, carrying a message. Erikson is honest to the message, he is not unsubtle and never facile, but he seems to reduce these characters to what they represent. What I’m trying to say is similar to a problem that Pynchon recognized in some of his own work: fist coming up with a theme or an idea, and then shaping a character around it, following with the plot and everything. Characterization well done, but coming after.

There is so much, many levels embedded in this book, that Erikson plays with (or could have played, since I always find so much in his novels that is untapped). But there’s also a feeling of scarcity. In the prose especially, but carrying over to characters, plot and setting. In the greater arc this is almost a blank state, so requiring more attention than usual to shape up things again. Pour life into this continent and the people living on it. It needs to be made “true”, to feel true. Become visceral and, so tangible. Linger with the characters and their lives, so that they acquire that true life, in the eyes of the reader. But Erikson steams on and only indulges in deep, solitary introspection, that doesn’t help shaping up these characters. It carves them inside, like tunnels down their personality and feelings, but lacking a certain “outward” development (see how I described it here). Too much bone, not enough flesh. It’s too pared down to the essential, to characters playing their complex thematic roles, in a complex thematic plot. Carrying along meaning heavy with implications but lacking the simplicity of a life and external relationships. I even felt a lack in descriptions, something quite rare in this genre. I’m used to Erikson’s style, but maybe I felt like he needed to shape things more fully, more all around, in this brand new context. Instead he only, selectively shaped what was immediately meaningful and relevant, without offering the illusion of this world existing and continuing just off the page. It felt so surgically precise and deliberate and purpose-full that it was cut off. Barebone, all too naked and dismaying in the way it seemed to carry little import.

At other times I narrowed down this problem to the blatant lack of “slice of life” type of narration in the Malazan series. Every character is a major player, or becomes one. Normalcy seems almost completely banished. And so characters sit more as plot devices, or thematic devices, or viewpoint warping, than some real people whose life you start believing in. That, for that reason, I’m able to follow and appreciate, but from the distance (the opposite of my reaction to This River Awakens). Another, shallower, problem is also born of something I started noticing in previous books, especially in the writing of the action scenes. It’s in these cases where I need the power of descriptions the most. The need to visualize and make tangible so that I can believe (I guess I’m also describing a failing of my imagination here, by voicing this). Erikson can write some powerful and evocative descriptions, but he always does this in very broad strokes, plus a tendency to “accelerate” the prose to match the action, so that the lines get shorter and just indicative. I find this counterproductive, as it achieves (for me) the opposite effect. Dramatic intensity is lost, because stuff happens without “weight” in the text. Being so succinctly described it is trivialized, quickly outpaced, moved off the page, so losing the staying power it requires (I’m also thinking at how modern movies tend today to do all action scenes in slow motion). And then I also get very easily confused by what is going on that quite often I have to read a scene two or three times to be really sure I understood what happened. So the whole point is defeated (acceleration of prose, I guess, to drive momentum, and dramatic intensity). Whenever I felt that the prose had to step up in the execution, Erikson instead seemed to withdraw even more. Become even more stingy with the prose, making it more perfunctory.

That’s mainly the nature of my criticism on this book. Descriptions are about the “action”, as much having in common that “lack” I lament about the characters and “life” around them. At some point there’s a scene, I think from Seren’s PoV, where she overhears some men talking about Hull in a tavern. I was almost surprised at the odd feeling of characters (Hull in this case) actually existing, written in the world. Because I usually get this feeling of them being so secluded in their own dimensions, like independent pockets. And I have a similar feeling about the rest of the book and the story. As if made of chunky bits, ably aligned, but not smoothly flowing and feeling connected.

Once again I should point out that, yes, Erikson is my favorite writer in Fantasy, but I am nitpicking. Being far less indulgent in writing a review of his book than how I’d be with any other writer. It’s because Erikson is my favorite writer in the genre that I expect the most, and more. And maybe the silly desire to see Erikson legitimately seen by other readers above other writers (or in as high regard), and so my implicit attempt to “flatten” his personal style to certain set of expectations I project on him (which would mean that all I wrote here is bullshit, a realistic possibility).

Putting all this aside, there’s still so much to admire in this book but that goes unmentioned because it is implicit in Erikson’s work and part of his specific set of expectations. I have admiration for his recklessness, as he always sets impossible high goals and then gets measured on those, even if the attempt itself is of mythical proportions. I was surprised that Theol and Bugg being so well received by readers in general, because it’s a kind of quirky humor based on wordplay and nonsense that is not a so safe bet. Their scenes work rather well and help to balance the other side of the novel, with the Sengar brothers, that is instead more moody and serious. I’m instead more doubtful at the end, where these two sides join to deliver the convergence and conclusion, the two different tones, humorous and bleak, clashing a bit together and giving me a sense of unbalance (that may as well be deliberate). The scenes at the Azath, through the book and especially at the end, never seem to come out of comic parody. The introspection, that I briefly discussed above and that is sometimes criticized by readers for burdening the text too much, is actually what I enjoyed the most, and considered the most inspired in the writing. It’s true that maybe it could have been spread more uniformly across the book, especially if there was an equally developed outward aspect. A character I was dissatisfied with was Ruhlad, because I felt his possession disfigured him too quickly, one moment going through unbelievable horror, the next already fixed on his task. He was misshaped, but not broken as I expected him to be. A too sudden transition where the character almost completely disappears into his functional role. Some characters, like Mayen, have a meaningful arc, but it’s so selective and surfacing only at times that it is quite hard to follow as a whole. You are forced to piece it together off the book, on your own. Sometimes these transitions are lost and feel sudden or disconnected. As if a lot of the quality of those characters stayed too submerged in the text, failing to surface and being fully appreciated.

I’ve said that the conclusion has an odd mix of tones, but it also carried a problem of being so sudden. As if you’re 50 pages from the end knowing it’s absolutely impossible that there are enough to make sense of all that is going on. As if the momentum that the plot gained would punch right through the back cover. When it comes to this Erikson is rather good at tying so many loose ends and give a number of character some kind of wrap up. In fact the ending definitely gives a sense of closure pretty much to everything. Satisfying. But it’s in going through the book again in my own mind that I wondered about a million of little things that seemed to go off stage without a mention. I thought there were in this book a number of Chekhov’s guns that did not fire, or misfired, completely subverting the expectations on which they seemed to be built. While in many cases the answers are explicit and right in the book, only requiring me to be more mindful and perceptive than how I was able to be (hence rereads being recommended). And others again being deliberate loose ties because intended to latch on following and previous books, to the greater arc of the Malazan series. I closed the book and more questions popped up at that moment than while I was reading it, but at least without undermining the experience (bad would be the opposite scenario: that the book provides all possible answers while still feeling unsatisfactory).

This also being the last of the “short” books in this series, at 270k (wordcount). From Bonehunters onward it will be about veritable doorstoppers, and I’m curious about the reaction I’ll have about the rest of the series, since I’m the one absurdly complaining that Erikson’s prose is too parsimonious. It took me an unbelievable amount of time to read this book, even if not because of its quality or enjoyment. But maybe this extremely drawn out experience I got of it also affected my opinion and the criticism I wrote here.

I wanted to conclude quoting a poem in the middle of the book whose message comes out with a particular clarity, so a nice contrast with those more heavily symbolic and hard to pinpoint. It also describes well a theme of the book, bringing it down to the most direct and explicit level.

The man who never smiles

Drags his nets through the deep

And we are gathered

To gape in the drowning air

Beneath the buffeting sound

Of his dreaded voice

Speaking of salvation

In the repast of justice done

And fed well on the laden table

Heaped with noble desires

He tells us all this to hone the edge

Of his eternal mercy

Slicing our bellies open

One by one.

In the Kingdom of Meaning Well

Fisher kel Tath

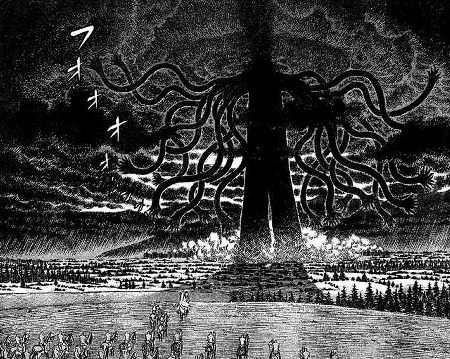

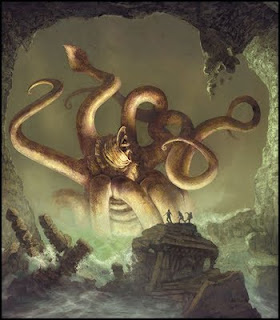

I’ve reached a point in the book where some big sea god makes its grand entrance. I was quite in awe and decided to write a bit about it, about how I perceived the whole scene and wanted it to be more than how it appears in the book. It has quite an evocative power but I feel that Erikson understated way too much such a grandiose event. It’s one awesome idea Erikson had, but that is dismissed in the multitude of other things. Other writers could have made this a dramatic pivot of a novel, but here it is somewhat resolved in three pages or so. 3-4 pages enough to introduce the threat posed by this unknown sea god, research its mystery, see it rise on the surface wrecking chaos, conclude the first battle and solve a first mystery. Too fast!

I’ve reached a point in the book where some big sea god makes its grand entrance. I was quite in awe and decided to write a bit about it, about how I perceived the whole scene and wanted it to be more than how it appears in the book. It has quite an evocative power but I feel that Erikson understated way too much such a grandiose event. It’s one awesome idea Erikson had, but that is dismissed in the multitude of other things. Other writers could have made this a dramatic pivot of a novel, but here it is somewhat resolved in three pages or so. 3-4 pages enough to introduce the threat posed by this unknown sea god, research its mystery, see it rise on the surface wrecking chaos, conclude the first battle and solve a first mystery. Too fast!