“I wanted all things

To seem to make some sense,

So we all could be happy, yes,

Instead of tense.

And I made up lies

So that they all fit nice,

And I made this sad world

A par-a-dise.”Cat’s Cradle – Kurt Vonnegut

Yesterday I was looking into the Metaphysics of Quality (MOQ). I haven’t read the Zen book, nor the Lila book, so I mostly read reviews of them, wiki articles and so on. In the end I didn’t have the desire to get the books and look more into this. It seems every other guy has created his own metaphysical system and his own “Theory of Everything” in the hope of having won the Magical Belief Lottery, and so the hope that one’s own system of choice is the one that ends up being true. This obviously includes Bakker, myself and so on, maybe with the difference that I’m personally more interested about “framing” the truth, than knowing what it is. What actually annoys me is when someone has to build his own system and technical terms when the system described is essentially the same of another that already exists, with its own shapes, forms and names.

I noticed that at the core of the MOQ, what seems the central idea on which the rest is built, is essentially a Kabbalistic system. This is how the MOQ is simplified: “Phaedrus describes evolution as going through four phases: the inorganic; the biological; the social; and the intellectual.” Already this is almost perfectly identical to the Kabbalistic basic principle, look at the diagram here. It’s confusing but look at the line at the bottom: Still, Vegetative, Animate, Speaking. You can draw the lines where you want, but the “intent” is exactly the same: you establish a hierarchy. Inorganic is the same as Still, Vegetative is equal to Biological. There’s only a little bit of confusion in the way the MOQ divides between “social” and “intellectual”, while the Kabbalah uses “animate” and “speaking”, but certainly “speaking” is “intellectual”.

I noticed that at the core of the MOQ, what seems the central idea on which the rest is built, is essentially a Kabbalistic system. This is how the MOQ is simplified: “Phaedrus describes evolution as going through four phases: the inorganic; the biological; the social; and the intellectual.” Already this is almost perfectly identical to the Kabbalistic basic principle, look at the diagram here. It’s confusing but look at the line at the bottom: Still, Vegetative, Animate, Speaking. You can draw the lines where you want, but the “intent” is exactly the same: you establish a hierarchy. Inorganic is the same as Still, Vegetative is equal to Biological. There’s only a little bit of confusion in the way the MOQ divides between “social” and “intellectual”, while the Kabbalah uses “animate” and “speaking”, but certainly “speaking” is “intellectual”.

The next step in the MOQ is about imposing on the model already described a moral hierarchy. So it’s: inorganic -> biological -> social -> intellectual. Each following step marking a “progress”. The “faith” implied in this system is that we’re moving resolutely toward betterment, that there’s a “plan”. Evolution pushes us toward improvement. Morality is simply defined by that direction. Whenever something on one level is sacrificed for something on a lower level, you have amorality. Whenever instead something on the lower level is sacrificed for something higher, then you have a moral and laudable choice. The wiki gives some examples:

Pirsig describes evolution as the moral progression of these patterns of value. For example, a biological pattern overcoming an inorganic pattern (e.g. bird flight which overcomes gravity) is a moral thing because a biological pattern is a higher form of evolution. Likewise, an intellectual pattern of value overcoming a social one (e.g. Civil Rights) is a moral development because intellect is a higher form of evolution than society. Therefore, decisions about one’s conduct during any given day can be made using the Metaphysics of Quality.

This simplistic explanation isn’t exactly convincing and I’m sure the book gives a lot more valid arguments, it’s not that I consider this pattern “weak”. What instead makes me skeptical of this whole MOQ is that it seems an attempt to build a formal system only to justify the author’s opinions. The Lila, where the author drops the narrative to focus especially on the theory, seems mostly focused on offering personal (or personal filtered through a formal, so non-subjective, system) opinions about the most disparate arguments. I read of: anthropology, sexual behaviors, the free market, celebrities, movies based on books, religious fundamentalism, the hippies and free love and so on. It seems like a kitchen sink of opinions, and it’s even plausible because if you go building a system of value then you are supposed to build it so it’s actually useful, and not so that it just lays there in its amorphous, abstract form.

But the true point is that we should shed the formality of these systems, and instead rely on their core ideas. If there’s some “true” value it is there, since the formulation of the system itself can as well be varied depending on who decides to formalize it. The idea at the core needs to be universal, the more it “belongs” to someone specific, the more it’s just a personal vanity. That’s why I get annoyed when one doesn’t simply recognizes structures that already exist and build on top of them. I think it’s way more useful to RECOGNIZE ideas that are in common, finding analogies between religions, in the hope that this redundancy, a recurring aspect, is the hint of something “true”.

This is true even for the Theory of Everything. The bottom line is that the more general is a theory, the more useless it is. The more specific, the more useful. Which is why someone said the Theory of Everything is equal to the Theory of Nothing. It’s so wide and general that it says absolutely nothing useful. Yet again falling in the trap of determinism versus metaphysics, the dualism on which the Zen book is based (to disprove). Once again we have a system caught between two almost specular infinities, the infinitely wide and the infinitely small.

Where I want to go with this? First, I simply want to show that the MOQ is a Kabbalistic system at its core. The fundamental ideas building both are essentially the same. You can draw the lines of the four categories in different places, or you can define six categories instead of four, but they describe the same overall pattern. The struggle for “improvement” that drives evolution in the MOQ is the same of the Kabbalistic “desire” that drives one realm to the next. The difference is that in the Kabbalistic system “desire” also drives from the speaking/intellectual level to seek for spirituality, or to seek answer to the meaning of life and so on (you can also refer to this).

My opinion, so, is that the totality of the MOQ is “encapsulated” within the Kabbalistic system of hierarchies. And I actually do think that the Kabbalistic one is more complete, more convincing and way better articulated than the other. So, as long you want to buy/have faith in this idea of progress driving everything, a “direction” imposed on the world, I’d rather follow the Kabbalistic system since it seems more powerful and have more to say and explain. The MOQ is essentially an important part, but still a small block within the much bigger system that is the Kabbalah. A first step on that ladder.

This was the premise of what I was moving toward. Which is the “isomorphism”. Essentially, the way the MOQ exists within the Kabbalah is something like an “isomorphism” between the MOQ and the Kabbalah (I did something similar when I recognized another isomorphism again between the Kabbalah and its reincarnation myth, and Pythagoras’ beliefs that I read about in “The Wayward Mind”). It is not important to look at the MOQ, and look at the Kabbalah. What IS IMPORTANT is to recognize the isomorphism. I said above that I’m looking for these kinds of equivalences, because they hold the hint of “Truth”. What are isomorphisms, and why I say they are so important?

It’s not me to say this. I was actually reading Gödel, Escher, Bach before I was reading about the MOQ. This time the real book, not wiki articles. It’s an incredible experience reading this book. From time to time it opens cracks into the Truth, and make you feel like you’re seeing what’s beyond. Sometimes there are lines that are oddly phrased to have a strange resonance, and what drew my attention, and what I now believe is the very foundation of REALITY, is this subtle yet very bold line:

I claim that the perception of isomorphisms is what creates meaning in the human mind.

When you read this in the book it seems almost insane, because at that point you’re just analyzing some mathematical/logic systems. He just gives you some games to play with, extremely simple and that could be tackled by a kid. And then at some point he comes out saying that something you’ve just “witnessed” (a result of one of these games), is actually the key to Reality. He says this candidly. This interplay at different levels is what makes this book so grandiose (and by the way, all of this I’m making my argument on, is contained within the first 60 pages of said book).

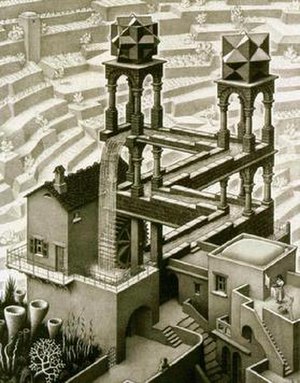

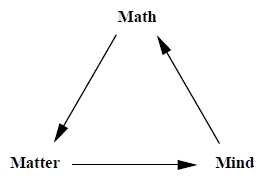

What he was doing is essentially this: he gave a simple game where you started from a string of characters (MI) and, through a number of rules, you could transform this string, some rules making the string longer, some shorter. The purpose of the game is deciding whether or not a particular string (MU) can be created accordingly to those rules. His argument was to show that a computer would start creating all possible strings, applying all rules one by one (as in the diagram above). But this would only produce exponentially more strings. The computer, hence, would go on forever trying all combinations, but without ever being able to “decide” whether or not the given string was possible in the system. What’s different, then, between an Artificial, deterministic, Intelligence and a human mind? The difference is the self-reference. The possibility of (or rather the impossibility of not) self-observing. This creates an impossible loop that creates an infinite hierarchy, a paradox. Gödel, Escher, Bach, in the title of the book, are “isomorphic” between each other because a “Strange Loop” is Gödel’s paradox (that can be simplified outside mathematics as the liar paradox), a Strange Loop is Escher’s Waterfall that you can see on this post (also, if you read DFW’s Infinite Jest, pay attention to that last line in the wiki entry, because IJ is ALL made of Strange Loops), a Strange Loop is Bach’s “Canon per Tonos”, that Hofstadter describes as “Endlessly Rising Canon”, “As the modulation rises, so may the King’s Glory.” “The “Strange Loop” phenomenon occurs whenever, by moving upwards (or downwards) through the levels of some hierarchical system, we unexpectedly find ourselves right back where we started.”

After the MU game described above, Hofstadter offers another similar one he calls “p q -” and it is soon revealed/shown that this system and its rules essentially mimic additions. “p” essentially represents the “+” sign, “q” the “=” and “-“, repeated symbolizes the numbers. He says that when you figure this out you give the system an “interpretation”. Then, he explains the difference between meaningful and meaningless interpretations. In this case the interpretation of the “p q -” formal system as additions is “meaningful” because it “reflects some portion of reality”. Ideally, if we believe in determinism, it should be possible to develop a formal system that reproduces the whole of reality.

What is the process that puts together the “p q -” formal system and additions, and so interprets it?

My answer would be that we have perceived an isomorphism between pq-theorems and additions. In the Introduction, the word “isomorphism” was defined as an information-preserving transformation.

Now look back at the quote above this last one. Could what just occurred in a simple game reveal the process behind the construction of all Reality? We find meaning by making associations. Recognizing this into that. I believe that the more you generalize this idea, the more powerful and revelatory it is. Don’t stay within the specific example. Make it universal. Make it the whole of reality. The perception of isomorphisms as the “canon” of the construction of reality. The implicit rule that defines every possible permutation (as within a formal system, producing all its “theorems”).

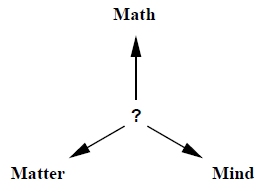

The idea of the isomorphism was also at the foundation of my objections to Bakker’s Blind Brain Theory (roughly: we are trapped within misconceptions, but what if our “picture” is wrong, yet still roughly “functional”? Faith may as well be faith in this purpose-driven possibility. That we are utterly wrong, but, after being spun, ended up being correctly oriented). In this long blog post I (probably) misused the idea of isomorphism, recognizing one between the Kabbalistic system and the MOQ. I also believe there’s a possible isomorphism between very complex science and metaphysics: the world is so perfectly ordered that whatever set it into motion is equivalent to god. In Kabbalah, god won’t and can’t intervene on “reality”, since reality is already so “perfect” that the need to “intervene” to adjust it would contradict its perfection. So the “hands-off” Kabbalistic god is essentially equivalent to what most scientists believe (or open to consider).

And finally, it may as well be possible that there’s an isomorphism between consciousness and Reality. This is the idea I explained in all the recent posts I wrote. That we face a mirror and that it represents the limit of our sight. We see outside, reality, the way we are inside. The world itself a self-description. The “isomorphism” may not be a process, but the “frame” that contains us and the whole of Reality (that we perceive). Our sense and meaning are just the retracing of our own patterns. The Strange Loops we see everywhere, we see because consciousness itself is Strange Loop-shaped.

I mention him here, this blog, because he was inspired by a similar sets of ideas, or beliefs. At some point he worked closely with

I mention him here, this blog, because he was inspired by a similar sets of ideas, or beliefs. At some point he worked closely with

I enjoy these kinds of meta levels, but in those cases where they are not a self-serving gimmick, like a thread that ties together all the works of an author. A message embedded in a certain worldview. I perceive an intriguing level of mythology in this, with a curious idea of time. Kurt Vonnegut has been defined humanist, which makes this level of metafiction and metaphysics quite interesting because it’s obviously not the proclamation of a “belief”. It’s instead the search for meaning where there can be none.

I enjoy these kinds of meta levels, but in those cases where they are not a self-serving gimmick, like a thread that ties together all the works of an author. A message embedded in a certain worldview. I perceive an intriguing level of mythology in this, with a curious idea of time. Kurt Vonnegut has been defined humanist, which makes this level of metafiction and metaphysics quite interesting because it’s obviously not the proclamation of a “belief”. It’s instead the search for meaning where there can be none. It’s curious that in the context of the purely agnostic (“we lack tools to understand what is really going on”) there are two opposite possibilities that seem quite popular these days. In one you could put Scott Bakker and a certain nihilism: the more we know, the more we realize we’re nothing. We decide nothing. Consciousness is not the center of the world, but the true fabric of the lie we cling to. We’re just trapped in a number of consolatory, vulnerable narratives that get constantly crushed under the heel of reality. The more you know the more you fail, because success is that vulnerable, erratic lie you tell yourself. It can only work as long you’re gullible, and quick on the self-deceit.

It’s curious that in the context of the purely agnostic (“we lack tools to understand what is really going on”) there are two opposite possibilities that seem quite popular these days. In one you could put Scott Bakker and a certain nihilism: the more we know, the more we realize we’re nothing. We decide nothing. Consciousness is not the center of the world, but the true fabric of the lie we cling to. We’re just trapped in a number of consolatory, vulnerable narratives that get constantly crushed under the heel of reality. The more you know the more you fail, because success is that vulnerable, erratic lie you tell yourself. It can only work as long you’re gullible, and quick on the self-deceit.  But returning to the idea of the “reality creator”, what got my attention was the idea of responsibility. There’s some of this even in Von Foerster’s Constructivism. The

But returning to the idea of the “reality creator”, what got my attention was the idea of responsibility. There’s some of this even in Von Foerster’s Constructivism. The