all my life I had tried to turn life into fiction, to hold reality away; always I had acted as if a third person was watching and listening and giving me marks for good or bad behaviour – a god like a novelist, to whom I turned, like a character with the power to please, the sensitivity to feel slighted, the ability to adapt himself to whatever he believed the novelist-god wanted.

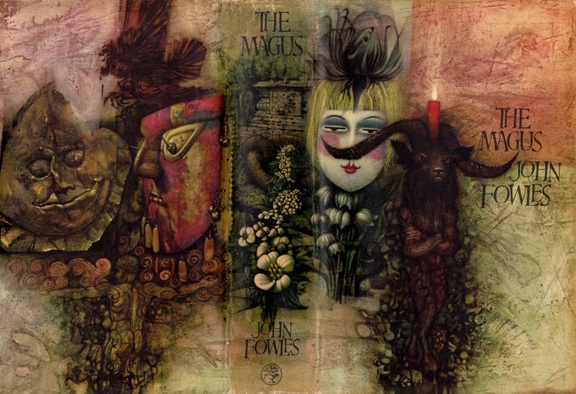

Slowly this blog has acquired a theme, and this book fits perfectly within it, or even frames it a ideal way. Story and structure make a perfect example of how it works, on many levels. I mentioned when I got the book that I specifically searched for the first, unrevised edition. There were readers’ reviews stating that the revised version had some of the original magic stripped out, in exchange for clarity, and of course I was more interested in the full power of that magic than clarity itself. But more importantly, for me, the existence of a revised version also meant that I would have something to fall back, in the case the book left me confused within the mystery. So if the magic was too impenetrable there was always another path to it available.

It may be I clamorously missed the point, but right now that I closed the book I’m of the opinion that it has a very clear, unambiguous conclusion. The book indeed has plenty of meaningful “magic”, but it did not leave me frustrated and wanting for answers. In fact it’s one of the most generous book among those I’ve read, everything is very clearly explained and not much is really left for the reader to figure out. The biggest mysteries are between lines of dialogue, in the gaps, but it’s a psychological, nuanced mystery, and not a matter of plot or unresolved parts left to the mists of reader’s interpretations. I guess one could see the few last pages as at least a bit ambiguous, but this is a case similar to Pynchon’s “The Crying of Lot 49”, the answer is there, laid rather explicitly. You just have to turn back a few pages, instead of staring blankly at the last one. But more importantly the protagonist doesn’t simply narrates the events, but constantly reflects about them, helping a lot the more naive reader to focus on the subtle points, instead of completely missing them. This is a book about true magic, but it is not a book for “initiates”. There’s enough of generous hand-holding to resemble Virgil in Dante’s Divine Comedy.

The smallest hope, a bare continuing to exist, is enough for the antihero’s future; leave him, says our age, leave him where mankind is in its history, at a crossroads, in a dilemma, with all to lose and only more of the same to win; let him survive, but give him no direction, no reward; because we too are waiting, in our solitary rooms where the telephone never rings, waiting for this girl, this truth, this crystal of humanity, this reality lost through imagination, to return; and to say she returns is a lie.

But the maze has no center. An ending is no more than a point in sequence, a snip of the cutting shears. Benedick kissed Beatrice at last; but ten years later? And Elsinore, that following spring?

This quote is the narrator telling the reader what to expect from a book’s ending, and this book too. True endings cannot exist, so the writer/narrator also surrenders here. But after stating the theoretical limits of every story, he also gives the book as much of an ending as it is possible, and as it is legitimate to ask. The maze has no center, in tone the ending of the book seems to wrap around to the beginning, but it’s not a true loop. The story reaches its ideal end, while the pattern instead goes on, repeats, becomes abstraction.

The only true lingering mystery is the one of the invisible hand shaping the pattern. Here intentions and motives seem more subtle and elusive, but the depth one perceives isn’t a false one or a trick. It becomes psychological complexity, and the rest is metaphor and power of narration. If you want to dig, you can.

Now I should clarify that the magic in this book is not of the kind of magical formulas, evil spirits or anything like that. We’re looking at the dark side of psychology, at the demons that hide in the soul and the mythological gods that give a metaphorical shape to every story. Magic is the hidden shaper of things, but the things are physical, and logical, and pretty much ordinary, I’d say. It’s “true” magic in the sense that it’s the magic that exists in this world, that is always there even if we don’t look at it, that we live in because we exist in consciousness. And consciousness is intrinsically magical and symbolic. It’s magical because of the gap between knowledge and experience, because we know the physical world is much weirder than everyday’s experience. But the truth is that we live in that world where the gods are real and shape our experiences, where metaphor is truer than truth, and so the metaphor itself is the only way to understand things at a deeper level (look up James Hillman, if you feel my words here are confusing). So this is a sophisticated, philosophical, psychological book, but with the merit of being accessible and engaging to read, no matter the type of reader. At the center there are excellent, vivid characters and a love story. But more to the point, it feels sincere and not hypocritical, as most love stories in books end up being.

While the love story builds the plot, the real focus is more inward-looking, introspective and quite solipsistic, in an infuriating eccentric and egoist and narcissist way. For the protagonist has its head firmly embedded up his own ass, depicted as a complacent nonconformist. This was a character I deeply hated with a passion for the first 60 pages. Since he’s also the narrating voice, it felt as a detached, cold observer, unable even of the most basic form of empathy. A pathetic human being that inflicts pain on others and only reacts with something between a casual shrug and cold, analytical observation. So, by contrast, it might be surprising that I slowly started to identify with him the more I read, and this identification was almost total, by the end of the book (though the actual end left me baffled again, when it comes to the character). This is obviously a goal of the book, showing a very complex psychological growth, but I think a theme is that perfection can’t be achieved, and realistically this character never really grows out of his faults to become someone else. We only get possibility, and that’s a call for honesty. As the book points out:

Though one can accept, and still not forgive; and one can decide, and still not enact the decision.

The book stays honest to the impossibility of perfection, of full forgiveness and atonement. What remains is just the journey and an ephemeral sense of freedom that remains the true mystery in the story. I mentioned at the beginning that there are different levels, and what I meant is that the story is only an occasion to dig into much bigger and abstract themes. This life, in the sense of the story that we look into while reading the book, is just a mean to get into those bigger themes and give them a recognizable shape. Allegory.

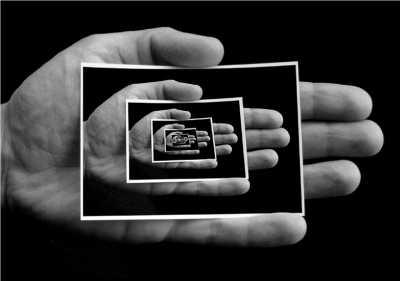

But here we come to what I care about, and why this book very clearly belongs to this blog. Like LOST and Donnie Darko, this is a story about manipulation. That’s also where the book escapes my interpretative grip (the theme of freedom). But there are aspects that I can see very clearly, as lighthouses, because it’s what I have my eyes set on, even before starting to read the book. This is another case of wheels within wheels, or more precisely of boxes within other boxes. Of mirror games and infinite reflections. At the end of the book, this thing is clearly defined: the godgame.

Now I saw Conchis as a sort of novelist sans novel, creating with people, not words.

The Godgame

– Imagine yourself a god, and lay down the laws of a universe. You then find yourself in the Divine Predicament: good governors must govern all equally, and all fairly. But no act of government can be fair to all, in all their different situations, except one.

– The Divine Solution is to govern by not governing in any sense that the governed can call being governed; that is to constitute a situation in which the governed must govern themselves.

– If there was a creator, his second act would have been to disappear.

– Put dice on the table and leave the room; but make it clear to the players that you were never there before you left the room.

The godgame is on one hand about hidden, or even explicit, manipulation, while on the other it is about observation. Life as performance, as if actors on a stage. You might or might not being observed. You can only speculate whether or not you’ll be judged positively or negatively, and you endlessly wonder about the meaning of it all, and the degree of freedom you have. In the book the godgame is played on various levels. There’s the story of the protagonist and his love affairs, there are also stories within stories, narrated by other characters, and there’s the “magus” playing the godgame on the protagonist, while the whole thing is still part of reality, and so the godgame that contains and shapes the whole of reality. There’s the godgame of a writer and the book he’s writing, and the reader subject to this godgame. Every godgame builds a cage around its “subject”, so that it is made possible, given definition. This is very much explicit in this book, and a delighted, playful interplay of different levels. Very well done, always stimulating and evocative and powerful. That’s the best part of the book, from my point of view.

There’s also an interesting perspective that is offered and that I found stimulating: what if at the end the subject meets his god, but the roles are reverted, and it’s now the subject that must judge the god. Will the subject forgive the god? Is forgiveness even possible? As you can see these questions mirror those I mentioned above, about the more tangible love story plot. And this because the different levels are meant to be transferred one on the other, seemingly the same but yet each offering something unique. The levels are the same, and yet far apart.

“Are you absolutely sure our actions have been nothing but evil?”

The “masque” in the book is similar to the Beatles’ Magical Mystery Tour. Story that becomes experience. A sort of adult “let’s pretend”. A god putting his subject through some dream-like journey of discovery and revelation. Characters in the book become actors, wearing masks, and you can never be sure of their true identities. From one story to the next, you can only let them lead you, play along. Unable to escape or affirm yourself. Caged, chained by the manipulation. Humiliated. Is this a tyrannical god or it’s all necessary and unavoidable, and we should be grateful for it? Is god a sadist? But in the end this is a book, the writer is the god, the protagonist of the book is who the reader identifies with. The relation between the magus and the protagonist is a mask for the relation between writer and reader. So you are part of the godgame, reproducing the pattern in all its meaningful parts. You are asked for empathy so that you can bridge the gap between reality and fiction. The disguise, that is literal in the book, also represents the writer’s tools.

The interplay is obviously deliciously post-modern, a game of mirrors, of pretense, of blurred identities. The godgame also reminded me in some ways “the entertainment” that James Incandenza prepares for his son in Infinite Jest. A kind of fictional device (again, a Magical Mystery Tour) that is meant to force its subject (Hal Incandenza) out of his shell. This too can be interpreted as a process of initiation and revelation, and it seems it’s rarely consensual (o you might think that consent defuses its efficacy). Once again, it’s judged as necessary, and you might or might not forgive your god, when it’s over. This happens all the same in a completely different, but still post-modern product: Evangelion. Where the father figure puts the son into a giant robot to fight aliens, just so that he faces his metaphorical fears and becomes a better human being. Even in this case the journey is explicitly allegorical, and again it’s efficacy is determined by the unification of various levels. The writer/god transposing himself in the book as a main character, and the identification through empathy of the reader/spectator with that character. Being him, sharing experience. A magical transference of parts and roles, through the power of fiction, and a transcendence too, because themes start from a particular story to become universal.

So you can put these different things so very close together: LOST, Donnie Darko, Infinite Jest, Evangelion. And The Magus. The first two maybe just for the interplay of levels, more than their “purpose”, but the last three have a much better overlapping identity and I can only wonder how they started from so far apart, only to converge on very similar points.

The ending of the book might be considered controversial, not much because of lack of answers or ambiguity but because it seems to wane in its magic power. In a way this is intentional, the book is structured in three different parts and the first and the last ones are very short and very different, and so they frame the real bulk of the book, where the magic takes place and the story is “elevated”. The writing also remains absolutely astonishing and excellent till the last page, so this waning of intensity is not directly a fault of a book, or a slip of author control, as I see it exactly as something necessary in the economy of this story. Though I admit I had a similar reaction to the one I’ve just read from Jo Walton on Tor:

it twists at just the wrong moment and sends it away from metaphysics into triviality and romance.

I had this EXACT same reaction, a building feel of disappointment that started somewhere at 200 pages from the end. But then it was defused the more I went on reading. As I said the biggest factor is that the writing stays consistent, and the writing itself is so magical and gripping that it can sustain even a weak story simply through nuance. But there’s also the aspect of the true nature of magic and transcendence, of the god’s play. In the end the magical is metaphorical sublimation of the ordinary, and so the “metaphysics” also need to return to the ordinary, at some point. The journey is not in one direction, but, as reflected by the mirror structure of the book, it returns. It takes flight toward magic, in Fowles own words “projecting a very different world from the one that is”, then it comes back down and returns to the ordinary. But in between something was obtained. This is the central theme even if you don’t pinpoint it on “love”. The lesson can be any lesson, and that’s why the metaphysical power is preserved. The initiation produced some change, even if it left you in the same place from where you started, now you are different and in some way renewed. You see the same things, but you see them in a new light.

It was like walking through a door, going all around the world, and then walking through the same door but a different door.

The penultimate paragraph is actually a full return to metaphysics without alienating completely the reader. I read it in the context of free will and human agency. “They [the gods] have absconded.” And then: “Fragments of freedom, an anagram made flesh.” And this matches with what Fowles writes in the introduction to the revision of the book:

God and freedom are totally antipathetic concepts; and men believe in their imaginary gods most often because they are afraid to believe in the other thing. I am old enough now to realize they do sometimes with good reason. But I stick by the general principle, and that is what I meant to be at the heart of my story: that true freedom lies between each two, never in one alone, and therefore it can never be absolute freedom.