I spotted a tiny recommendation for the Malazan series, on Twitter, and I got carried away adding some of my unsolicited thoughts to it.

I always said that Malazan is very hard to recommend to other readers. For example it’s a lot easier to recommend Sanderson, despite Sanderson not really needing any help to get known, since now he’s all over the place. But it’s accessible, and pretty good for a very wide range of reader types. You can read 100-200 pages and see by yourself where the qualities are. And know whether it’s your thing or not.

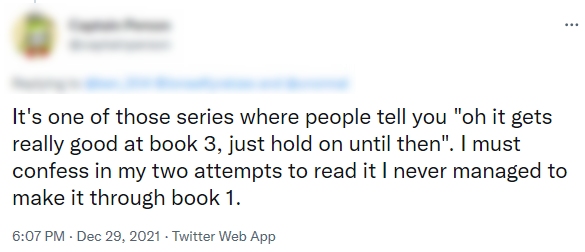

Malazan has this, instead:

To a certain extent, it’s true. But it’s still a narrow explanation. I ask often myself, why am I a Malazan/Erikson reader? What do I find there? Why it’s so important for me? Malazan is recommended a lot, often next to the more popular Martin and Sanderson, but I’m convinced it has a very low “success rate”. I mean readers who accept the recommendation, give it an honest try, but end up not enjoying the read at all. I always asked myself why.

For many, it’s all about a matter of taste and personal disposition. But that’s not a satisfying explanation for me. I always seek a reason, trying to find an objective motivation… that can describe what is that precisely works for me, and doesn’t for other readers. Many others.

I think I grasp at least some of the reasons why it happens. When I recommend Malazan I try to give objective, useful information. It doesn’t mean that I diminish the qualities there, but I do emphasize what the obstacles will be. And it depends on who’s on the other side of the recommendation. Because of the above, and because Malazan is huge, the main dilemma is that the reader doesn’t know if it’s worth committing. Therefore, the paradox: do I commit to read thousands of pages? Where is the threshold where one stops and decides if it’s worth continuing or better stop and read something else more satisfying?

That’s where I draw the line. Do you intend to commit to something huge, from the start? Fine, follow “the rules”. Start at the beginning. But if you are undecided, skeptical, and you want to know what’s there before fully committing, I’d suggest some …alternative, unconventional paths.

Garden of the Moon, the first book, is not a bad introduction to Malazan, but it is a bad introduction to Erikson. Its themes are buried very, very deep. Easy to miss. On the other hand you are buffeted by a million of things thrown in your face, constantly, vehemently. Scenes that seem inconsequential get lot of attention, scenes that are pivotal, or fundamental information end up being omitted only to be referenced offhandedly much later in casual conversation… or just vanish like a dead end. Sometimes things seem pointless, sometimes it all seems coming in the wrong order. Most readers feel confused, or detached from everything.

Eventually, through a lot of patience and a certain devotion, you read a few thousand pages and you have a map. You become the Malazan reader. Knowing where each piece fits, even appreciating the gaps, for they have an use too. You understand what, where, and why (a bit less when, but that’s not so important… Just to make a joke about the often criticized chronology that on occasions is a little wobbly).

Most successful writers use some proven “devices” to seize the reader. The book must have the reader in its center. The book is about Harry Potter, you identify with Harry Potter. The book is about you.

Me, me, me, me. I want the book to be about me.

The focus needs to be all about the reader, feeding this hole of attention. Malazan does some of this, but its greater part is the opposite. Kicks you out: fuck off, get out of the way. Take yourself out of focus, and maybe something worthwhile can be said. Stay quiet, observe. I’ll return to this…

Malazan is not lonely, but it is solitary, brooding, a bit forlorn. Especially now it represents the time. With lockdowns, being separate, and yet it’s now that we’re all connected, more than ever. And we can observe all, everything around us, collapsing. Governments that blindly repeat actions that have failed, imprisoned in a psychotic loop, rewriting and bending science to what’s more convenient. Over and over we know, with clarity, that measures are effective the more they are timely, focusing on prevention, and what we do is the opposite, we wait until too late, feeding onto a pervasive fatalism. We simply accept a number of deaths, making it a norm. Minimizing risks to make believe everything’s fine. Follow these five simple rules for a false sense of security. All because the world doesn’t want to change, and power needs to be preserved. And we can only observe, passively, this slow, progressive deterioration of reality itself. We just observe from our places. Solitary observers of something set into motion. Sorrowful but unable to act, like ghosts.

Malazan is the pain of the world, when it is spoken through a living or unliving mouth. You are meant as the vessel, Itkovian.

That’s why I sometimes I suggest a new reader to start with “Forge of Darkness”. If you are uncertain, whether or not to commit. You could start from the proper beginning, but you’ll have to dig, probably for a long time before you find those themes. Forge of Darkness is not an introduction, but it can be read on its own without prior knowledge. It might feel that you’re missing pieces you’re meant to know about, but you have to trust the text. The book is confusing even for veteran Malazan readers, in some cases even more because it plays around by scattering some expectations. You can go in blind, but read slowly, give it thought. Malazan is not a page turner, even if it has page turning scenes. Mull on the paragraph you’ve just read, not thinking about it only after you’re done. Dig for meaning.

Forge of Darkness is a brooding, mysterious book, but it has its themes on the front, explicit. Impossible to miss. You want to know what it’s all about without reading a million of pages, then it’s all here, wrapped up and well presented. One book, even if part of a trilogy it’s sufficiently self contained. Not an easy read, but it’s there, and you’ll see it.

But I wanted to go further. Condense more, to a point. What is Malazan about?

“Secret… to show… now.”

https://loopingworld.com/misc/erikson-test.zip

(This link includes two scenes, one from book 2 Prologue, one from book 7 Prologue. Six pages in total. No spoilers. You can read these without knowing anything else. The images are taken from Amazon previews.)

I read this prologue and this scene many months ago, but I immediately realized… This is Malazan, right here. Just three pages. It’s everything.

A woman walks up to this cliff. For the reader this is a blank page. You get the description of strong winds, the ocean beyond. Agitated waters. You get a mention of a Meckros City that sunk there. If you are new to the series you know nothing about it, but me, Malazan reader, don’t know all much more beside that these people built floating cities on the sea. So they knew how to be out in the ocean, and the fact they sunk here leaves an ominous feel about the place.

Like a painting, a white canvas, you add detail. Brush strokes. This vast open space in the ocean. You follow with your mind a small fisher boat, blown off course to these treacherous waters. Miraculously surviving the experience and reaching the shore. But something is missing from the picture. Something like a shadow, looming on the scene. Depending on what you use, there’s always an exclusive, irreplaceable quality. For example, in a movie you can use some tricks, but you show what you have to. The attention goes where it has to. But in a book, you control everything. You decide what is or isn’t there. Here you believe what you’re told. You have an ocean dominating the canvas, and then your attention is drawn to a tiny boat, thinking it’s the center, when it is instead pushed to the margin. There’s a giant shadow that dominates the canvas… but no perception of it. Just… A sense of urgency. A secret… to show.

The wind pushes her away, she endures. Drawn to this shadow. Some more details seep in, but the scene is interrupted by “a presence at her side”. A distraction. A merchant she completely ignores. He makes his presence known, loudly. He’s ignored again. The shadow is there, like a tear in reality. The wind rushing out of it, from a different world (a warren).

“Preda?”

“What?”

He tries to shake her as if she’s asleep or in a trance. She didn’t turn to him, she didn’t acknowledge his presence. It’s the shadow that draws her. And bit by bit, it is revealed. Half a million people that just vanished.

It’s already all here for me. The way a mystery is shaped, the choice of what is and isn’t shown, the momentum leading to the revelation. The contemplation, and an environment that takes shape to become a character. Telling its story, piece by piece. The sense of urgency that builds up… for something already happened, already over. The scene, beside the wind, is quiet. You don’t need to read 500 pages for the solution, in two/three pages you get both the set up and the pay off. A book of 900 pages, in a series of 10 book, and you get the pay off in three fucking pages. The mystery isn’t inflated and built by pretense, it’s there. Immediate. Fully delivering its awe. And when the answer comes, to fully deliver its promise (what is she seeing, why does the sight chill her?) you get an opening for more. It’s just an introduction.

And, why not? We see a woman, commanding the military, ignoring and then bossing around a rich, probably powerful merchant. There is no emphasis about any of this. It just is.

(imo, this scene already has too much dialogue, too many asides. It could have used less. Erikson, who’s never generous, already gives too much. Erikson works better the more he’s entrenched. Going the opposite way. Say less.)

I’m not commenting the other prologue scene because there’s a lot, and most of it is quite explicit, even if open ended. But it’s ironic that I could write a lot about those first three lines: “What see you in the horizon’s bruised smear, that cannot be blotted out by your raised hand?” What other witty commentary is possible when it’s all so straightforward?

Well, for me Malazan is always about a sense of scale. Big books, each one, ten of them. A sense of history, a large cast of characters, a big world, creatures, dragons. And yet it thrives on the small, intimate. Introspection. Often duos on their solitary journeys, like Mappo and Icarium. The human, more intimate scale (hand) is always the view on the world, on things much bigger, the gods, alien worlds (the horizon). A sense of reality that has to go through the filter of human perception. The world through, or into your hand. Animated. A construct. Maybe even a pretense of control, that is always mocked. Gods that are dragged, taken down. Heboric again. Erikson always plays with scale, and knows what he’s doing.

(btw, Paran – Felisin – Laseen, make an important pillar for the first FOUR books. And it’s omitted. Nothing about it is shown. Imagine reading Game of Thrones… and there’s no chapter on the Starks. The story is the same, you just don’t get any direct view of them.)

Malazan can be summarized in a word, a concept. Malazan is… “contemplative.”

It is all about the voice. If you take Lord of the Rings and you know Tolkien was a linguist, you’ll realize that everything that makes LotR what it is, to its core, is language. Language is the filter for everything, something that Bakker understood really, really well. It’s not one possible angle on that book. It is everything. It’s a dimension. Even the metaphysical/religious aspects are all about language (the elves who represent art, immortality, the god-like power of creation, and the world that begins shaped by music, all is a form of language).

Something similar happens in Malazan. Erikson was an archaeologist. This well known fact is often used to explain why the worldbuilding is so good. Because that knowledge gives Erikson a way to look at things, make them more realistic. But I think that worldbuilding in Malazan is extremely overrated. Even Sanderson that I mentioned above does worldbuilding better and more meticulously. What Erikson does is something else, and it is pervasive in the same way language is pervasive in LotR. An archeologist is someone who walks onto a site. He looks around, observes. Contemplates. He reads the place. In his mind he interprets the signs he sees, connects them. He imagines the people there, the culture, the life and blood. He walks though a place that is no more, and yet still there. Like a ghost, walking through an alien world. Or the reverse: a shaman haunted by ghosts.

Being an archaeologist, an observer of human culture, isn’t an angle, a point of view. It is an enclosure of the world. A receptacle, a symbol. An almost religious experience. Like Heboric before the Jade Giants.

How to observe the world, species, your people, your life?

How to understand things, how to give them meaning?

The same as Heboric in front of the Priest of Hood, there is a sense of urgency. But it’s about the world, not you. The observer is Felisin, not Heboric. It is not you. Felisin that came from a different world:

“The same city, but a different world.”

Passivity is her theme through the book. The flies crawling on her thighs are the least terrible thing that is going to happen to her, nothing is normal anymore. Her world collapsed, leaving her not even scared. Just numb.

This flow of human events that seems nonsensical, vain, empty.

Like Heboric watching the Jade giants, Heboric and the ghosts of a world that is no more: I observe my time as if I’m outside, but I am in it. And yet outside, observing with an external god-like quality… of inaction (powerlessness). There’s nothing to judge, because it’s like a river. It goes downhill. It’s not its merit, it’s not its fault. You get to understand it only when you aren’t anymore part of it. Because when you are in it, you are swimming for your life. The world is about you. You cannot understand the world until you surrender yourself to it. Until you stop pretending to decide its course.

Silence your ego, lets the world speak with its own voice. You stop deciding, you start understanding.

The secret of Malazan is transforming its readers in… Ascendants. From reader to witness. We are the witnesses, from this outside. Given sight.

The writer is a jade giant, the reader is a jade giant. We are all jade giants. We watch. Erikson teaches how to tune in. To the hum of the world. We give voice to these otherworldly giants. We are receptacles. We are vessels of the world. We do not find answers, we must answer.

(The buzzing of Hood’s files, they speak. The buffeting wind, it speaks. “The world is very, very old.”)

(In Game of Thrones Martin transforms Bran into a tree. He can do it. In Malazan, he cannot do it, Erikson transforms the reader.)