After finishing Dune, my review will be up on the sites within a few hours (or tomorrow, I didn’t have the time), I can now move on some interesting things.

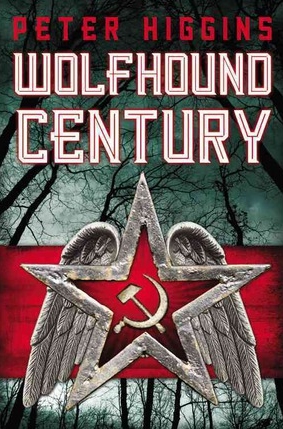

Queued next are the return to Bakker’s series, The Warrior Prophet, and, for once, a newly released book that at 300 pages is relatively short, and so I can hope to review it within 2-3 months from release: Wolfhound Century by Peter Higgins (the page with the book covers listing the books that have influenced the writing is particularly interesting).

This book got my attention when Gollancz announced it almost a year and half ago. That press-release had an inordinate amount of “hype” (which isn’t always a good thing) but also lots of things that tickled my curiosity:

After a hotly fought auction, Gollancz Deputy Publishing Director Simon Spanton has snapped up a stunning debut spy thriller set in an ‘other’ Russia.

Spanton acquired world rights in 3 novels by Peter Higgins, from Ian Drury at Sheil Land Associates, after a fierce auction between several publishers. The first book in the deal is Wolfhound Century, due for publication in 2013.

The novel is set in a grimly authentic totalitarian state, an alternative Stalinist Russia where timelines and alternate histories intersect.

But beyond the state, is a land of endless forest and antique folk lore.

Forest and folk lore are of no concern to Inspector Vissarion Lom, summoned to the capital in order to catch a terrorist – and ordered to report directly to the head of the secret police. A totalitarian state, worn down by an endless war, must be seen to crush home-grown terrorism with an iron fist. But Lom discovers Mirgorod to be more corrupted than he imagined: a murky world of secret police and revolutionaries, cabaret clubs and doomed artists. Lom has been chosen because he is an outsider, not involved in the struggle for power within the party. And because of the sliver of angel stone implanted in his head at the children’s home.

Secret Police chief Lavrentina Chazia sends Lom in pursuit of notorious revolutionary Joseph Kantor. She conceals a great deal from Lom, but cannot disguise the hard patches on her palms as her hands are turning to stone.

Lom’s investigation reveals a conspiracy that extends to the top echelons of the party. When he exposes who – are rather what – is the controlling intelligence behind this, it is time for the detective to change sides. Pursued by rogue police agents and their man-crushing mudjhik, Lom must protect Kantor’s step-daughter Maroussia, who has discovered what is hidden beneath police headquarters: a secret so ancient that only the forest remembers. As they try to escape the capital and flee down river, elemental forces are gathering. The earth itself is on the move.

For, a thousand miles east of Mirgorod, the great capital city of the Vlast, deep in the ancient forest, lies the most recent fallen angel, its vast stone form half-buried and fused into the rock by the violence of impact. As its dark energy leeches into the crash site, so a circle of death expands around it, slowly – inexorably – killing everything it touches. Alone in the wilderness, it reaches out with its mind.

‘We found ourselves in a fierce auction but as it went on the book kept reminding me why I didn’t want to lose it. We’re delighted to be able to welcome Peter Higgins to Gollancz.’

So now the book is out and I ordered it, thought it will probably take a couple of weeks to get here. There are hints about huge complexity, mythology and lots of imaginative power. I don’t know how the author is able to fit all that into 300 pages but I really hope this will be a great book.

After I read that press-release I decided not to bookmark it since I thought that if it was a big thing I wouldn’t miss it anyway. And so a year later I started to search in frustration about this book that I vaguely remembered and that I couldn’t find anymore. The things is that I also confused it with another novel: Ice by Jacek Dukaj, that is also worth mentioning. From a reader:

Reading Lód (Ice) by Jacek Dukaj.

It’s an epic (1100 pages or so, dense) tale taking place sometime (I think) last century in a world where history was stopped by a mysterious event in Tunguska; among other things, Russia is still an empire that owns a large part of Europe. This event has caused the appearance of Ice, a strange form of matter (aliens? other dimension? not sure) that is slowly spreading outward, altering the shape of the world, from philosophy to industry to physics.

I have no idea where it’s going, but it’s a great read so far. It has Tesla in it, which is always good.

This is a Polish novel untranslated in English. It’s the one book I’d really like to read the MOST. It’s 1000 pages doorstopper that got raving reviews. All the themes in the book are “my stuff”, so it’s really something I WANT. Now. Like a kid who can’t wait. But the problem in this case is that, despite what the wikipedia says, nope, there’s no translation in the works. Read his TVtropes page. I WANT THIS STUFF.

His protagonists often struggle with their identity, typically (but not universally) starting as weak or broken, but slowly gaining strength and rising as powerful leaders, sometimes reaching “A God Am I” status. Many of them are or become Transhuman of technological kind.

The first line of this book is already memorable:

“It was on the eve of my Siberian Odyssey that I first began to believe that I don’t exist.”

Come on, publishers. With all the useless mediocrity published every day, why can’t I have nice things? I want this novel in a language that is readable. Then, after you’ve published this one, go on and publish everything else he wrote too.

Fuck The Witcher, bring me Jacek Dukaj.