And now I fear that I am not unusual, not cursed into some special maze of my own making. I fear that we are all the same, eager to make strangers of the worst that is in each of us, and by this stance lift up the banners of good against some foreign evil.

But see how they rest against one another, and by opposition alone are left to stand. This is flimsy construction indeed. And so I make masks of the worst in me and fling them upon the faces of my enemies, and would commit slaughter on all that I despise in myself. Yet, with this blood soaking the ground before me, see my flaws thrive in this fertile soil.

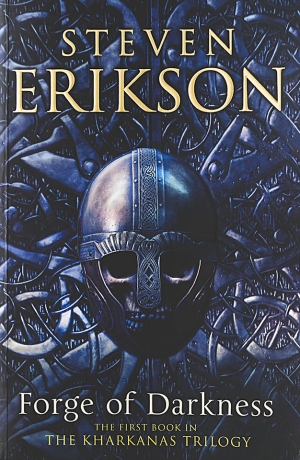

Reading this book was for me a stimulating experiment. “Forge of Darkness” is the first tome in a prequel trilogy, to a series that is ten books wide. Naturally it would be read by fans who went through all the ten, huge books building the Malazan series. I’m one of them, but I read at my own pace and I’m exactly halfway through that series, ready to pick up “The Bonehunters”, the 6th volume. I decided instead to read this one first. It was an occasion to read the book when it came out (or at least within a few months) and to make a contrast between books that shared themes but separated by some meaningful years. So that I could see more clearly how Erikson’s writing changed and if that direction was one I “approved”. About a year ago I read “This River Awakens” that, while not Malazan, I considered his best book, and it was written years before even the first volume in the Malazan series. It was not exactly an encouraging perspective. So I’m glad to say, bluntly, that in my personal Malazan ladder, this book comes first, above the other five in the main series that I’ve read (it goes like this, for those who recognize these codes: FoD > HoC > MoI > DG > MT > GotM).

I read the book holding some kind of three-way perspective, which was not forced. Usually when I try to write down a review my goal is to give a sense of that book, especially about why one should read it, instead of millions of other books out there. Like a sense of urgency. What sets it apart and gives it its uniqueness of flavor. In the case of long series there are three perspectives. First there’s my own, the very personal and emotional response that rises spontaneously and that one has then to struggle to rationalize in clear patterns, then there’s the perspective of readers who know well if not the book, at least the series, author and setting, and finally readers who are completely new. In the case of this book all three are particularly interesting since it’s a prequel, and so, already in the intentions of its writer, a possible starting point for brand new readers (as well veterans who still have not finished the main series).

Is “Forge of Darkness” a good starting point for readers who have yet to pick up the Malazan series? Initially I thought it was. The writing is measured and careful, so easy enough to follow without feeling lost. The problem is that from the middle point onward there are a number of mysterious scenes steeped in myth that were confusing even for me, who ravel in that kind of thing. So I would say that reading this book first is definitely possible, even recommended, but it comes with some conditions. It is not an easy book. It is extremely demanding. From one side it will make understand a reader what’s the (real) deal with the Malazan series, whereas “Gardens of the Moon” is nowhere as clear about what is that sets this series apart from everything else. But from the other it could discourage a reader even more than GotM because it’s a steep climb that demands a lot from the reader, and to engage with it deeply. The story has better hooks and it can be more seducing, it isn’t baffling, impersonal and confusedly crowded as GotM was, but it also lacks the lures one expects in epic fantasy: the journeys, visiting places, meet peoples, big setpieces. All these do exist, but are twisted in the unique Malazan way.

Erikson said that, as the Malazan series was conceived as an homage to Homer, the seed of epic fantasy, these prequels would be another homage, but to Shakespeare, the bard. Pretentious claim, everyone would say. Whether deserved or not, I recognized this particular air (and the setting is also particularly suited). The PoVs and scenes in this book have a perceivable theatrical quality. Sometimes I perceived that “enter” and “exit” lines that built a scene, characters coming on stage, facing each other. Erikson always used this style, this time slightly different because often the next scene follows logically the one before, and so reducing the jumps in context typical of Malazan, but this time it gives a sense of a play and contained space. These scenes remain intimate, usually not more than an handful of characters interacting. Malazan was more sweeping wide, panoramic and movie-like.

This time things are personal and stay lodged tightly with the characters even if events have a big import. “Worldbuilding” is interesting because built in a false way. This is not a typical fantasy backdrop, here less than Malazan proper, that objective world that is stated with certainty. The fantasy, secondary world built as an independent, whole thing. One of the lures of reading fantasy can be this escapism, the seduction of a different, fascinating world finely detailed and precisely described. Instead I call what Erikson does “false worldbuilding” because it stays on the characters. The world shifts and blurs, is shaped and defined by the characters who live within it and that observe it. Things either have subjective value and meaning, or do not appear. And it is only in the opposition of the many PoVs that you can perceive it as something whole.

It is in my nature to wear masks, and to speak in a multitude of voices through lips not my own. Even when I had sight, to see through a single pair of eyes was a kind of torture, for I knew – I could feel in my soul – that we with our single visions miss most of the world.

The value in what Erikson does, compared to other Fantasy writers who don’t always have it in focus, is in the “metaphor made real”. This could become just a tiresome trick on its own when simply repeated, but the strength is about knowing what you write about. The reason why it’s so important is that it builds a true resonance with what’s meaningful. A story grips a reader when it builds a bridge, between what happens on the fictional side and what’s deep in the reader (and that’s also the distinction with escapism, wish fulfillment and all that). You could fashion clever magic systems and cool looking demons, show epic battles, but those demons only have true power if they come deep from one’s true soul. In this book even more effectively than anything else I’ve read, Erikson turns the human being inside out. What is shown is the dark side of the human landscape. Those true demons. Those that truly scare you and won’t go away, ever, when you turn on the light or when you grow up. It is done without rhetoric and embellishment. Without spectacle and complacency. From my point of view, this is Erikson at his apex.

Erikson at his best, excellent prose. Filled to the brim with beautiful and meaningful lines. It is a pleasure to read, but it also rather dense and can discourage readers who do not engage on this level and prefer something that has a brisk, lighter pacing. Or something that doesn’t take itself so seriously. Erikson is known and often criticized for heavy-laden introspection and one either has interest in it, or this book can be incredibly daunting and tiresome (especially with it moves toward the cosmogony of myth, which is a theme of this book I simply love and find, oh, so incredibly interesting). I’d also say that this is the one that the most gets close to the work of Gene Wolfe (without any of that artificial affection that I see in Wolfe), also admired for beautiful, meaningful prose and criticized for lack of ease of access and flow of plot. Lots of interesting, pivotal things happen, but as I said this is colored by what the characters see and their thoughts. The landscape has a dream-like flavor and also gives it an haunted atmosphere.

Many times Rise Herat had seen a face stripped back by the onslaught of loss, and each time he wondered if suffering but waited under the skin, shielded by a mask donned in hope, or with that superstitious desperation that imagined a smile to be a worthy shield against the world’s travails. These things, worn daily in an array of practised expressions insisting on civility, ever proved poor defenders of the soul, and to be witness to their cracking, their pathetic surrender to a barrage of emotion, was both humbling and terrible.

It is not an easy book because it’s often, always, a punch in the gut. It is not simply bleak to the point of being mono-tone. As usual Erikson shows the full range of emotion and there is humor and lighter scenes. But that human warmth and friendship is always a very narrow ledge that opens on a Abyss of miasmatic chaos, always eroded. A frightful thing. Like a candle light in a forest of darkness. There isn’t (anymore) any conceit about what Erikson does with his writing, and no attempt to reassure the reader after an hard experience. Those decorative curtains are torn away. Reading this book is like drinking wine on a empty stomach. There’s is lots of beauty, but it’s also mean and bewildering. This is thick and heady wine, the kind that takes quite a toll.

I’m still answering that question, the answer is: read it if you dare. Expect an exhausting book. The reward is an unique one because I’m simply not aware of another writer who achieves as much. Simply. You think it’s “hype”, for me it’s being honest. What Erikson writes contains the breadth of the world. Any world. And as far as I know no one has ever attempted to do the same. What Tolkien did was incredible, especially in the latter part, post-LotR, and Erikson indeed sits on the shoulder of giants, but he sees further away and describes that he sees better than anyone else. This book is a distillation of all the qualities the Malazan series possesses (and none of the flaws and growing pains I recognize in it), by a writer who’s now probably at the very top of his skills and is no more struggling to find his voice as he was in “Gardens of the Moon”. If you want to know right from the start what Malazan is about, then this book is ideal, but if you want to take it easy without being plunged on the very deep end, then start from the beginning of the series.

P.S.

I also believe, contrary to what everyone would say, that this book is perfectly self-contained and doesn’t necessarily need the two upcoming books that will complete the trilogy. Some (most?) PoVs are left hanging, but but not in a frustrating or dissatisfying way, and the book has its cohesion.

Suggested reading:

– Larry’s review of the book, because he did this time a so much better work than me, whereas I always try to be spoiler free that my own end up being so generic and bland.

– This on Tor site, because it’s a newcomer perspective (even if plagued by way excessive retconning to familiar canons, which doesn’t help at all understanding Malazan) and because I like “The Silmarillion as told in the style of A Song of Ice and Fire”, only that Erikson ends up writing better than both of those writers ;)

An illness that entirely gets to represents his only identity (left), and the truth of the impossibility of hope. In that condition he viscerally knows his harsh reality, and he knows that delusions come in the form of fantastic narratives. Fantasy landscapes where all illnesses can be healed, a natural world manifesting itself as pure beauty. With his feet in these two radically different and opposite worlds, he is lacerated. Torn from the inside. And he leashes out with pure anger because he’s painfully aware of how these delusions of hope and health are mocking his true condition. If you, the reader, go into the story, then it’s the fantasy world coming alive and being real. But if you instead take this story out and make it true, then you feel how powerful it is, and how much unsustainable pain it delivers.

An illness that entirely gets to represents his only identity (left), and the truth of the impossibility of hope. In that condition he viscerally knows his harsh reality, and he knows that delusions come in the form of fantastic narratives. Fantasy landscapes where all illnesses can be healed, a natural world manifesting itself as pure beauty. With his feet in these two radically different and opposite worlds, he is lacerated. Torn from the inside. And he leashes out with pure anger because he’s painfully aware of how these delusions of hope and health are mocking his true condition. If you, the reader, go into the story, then it’s the fantasy world coming alive and being real. But if you instead take this story out and make it true, then you feel how powerful it is, and how much unsustainable pain it delivers.