How to fit a large box into a smaller one?

In this issue we reach a cosmology so wide that it eventually fits down to a single character: Moira once again. I enjoyed this inversion.

Overall, this closes the sequences, but it doesn’t resolve much. The trick was quite simple, but it was unexpected, at least for me. The only problem is that it leaves the whole structure wobbly and unconvincing, but we’ll get to that point (maybe).

The only aspect resolved is the mystery of Moira’s 6th life, and the surprise (plot twist!) finding out that what we believed was the future was instead in the past. It works. Hickman trained us to think that these pieces of story, in time and space, were segments belonging to the same block. The trick was showing the last segment from a previous block, without saying what it was. Sleight of hands.

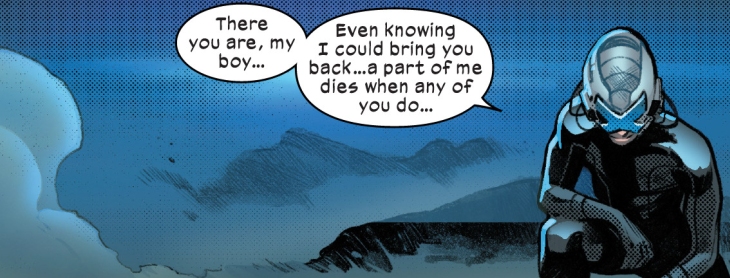

This time it is interesting because the plot twist isn’t an end to itself, but it opens a view… The key to everything is the dialogue between the High Evolutionary, uhm sorry, the Librarian, with Moira and Wolverine of the future (but the 6th future). There are signs everywhere hinting things are not as they seem. A few pages after, Wolverine kills the Librarian, but if you go at the beginning you see that this is the second attempt, and the first was easily deflected. Now, it’s not very clear if that first attempt was also made by Wolverine or some other mutant, but the scene wants to be ambiguous and tell us that the Librarian isn’t taking any risks. Wolverine might be good at what he does, but he doesn’t seem to be outside the “scope” of the Librarian. This is just one of the hints.

More importantly, the Librarian is speaking to Moira in the way silly villains sometimes do. Giving our heroes plenty of hints on how to better defeat their enemy. He is “slyly” suggesting Moira and Wolverine to kill him before he gets to the hive mind, or then it would be too late to do anything about it, since the hive mind exists outside time and space, so on a hierarchy that should be superior to Moira’s time travel quirks. Once he gets there, game over. And in fact the moment when Wolverine makes his move is the moment the Librarian is… talking over his shoulder, conspicuously offering his back.

The simplest, most straightforward interpretation is that the Librarian planned his death. It’s a deliberate move, that works quite well with the overall idea. Although this leads to wider problems outside the scope of the story and plot. But let’s stay inside, for now.

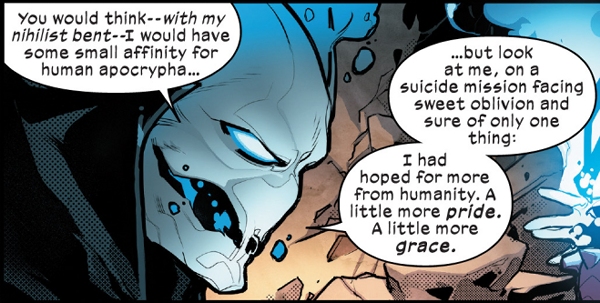

There’s a nice bit of Blind Brain Theory-like concepts here. Concepts of blindness. The first offered right away by the Librarian: “How could anyone want something they don’t know exists.” It’s the anosognosia of knowledge. You need information on the missing information to know information is missing. Same as we didn’t expect that this future segment belonged to the past.

That’s why the actual plan of the Librarian doesn’t seem to be to let Moira ad Wolverine free of preventing that future, but simply to let them BELIEVE they can. To let them believe they are ahead, they are still in control because if they kill the Librarian before he gets to the hive mind, then they both are HIDDEN to the hive mind sight (knowledge). They are the blind spot.

This seems and feels logical, because the Librarian explains why he’s full of doubts about joining the hive mind, and this is the only way to prevent a move that cannot be undone. But the position of one who’s doubtful isn’t the position of one ready for sacrifice. That’s more generally the position of one who waits.

To me, this paints a more plausible scenario where the Librarian merely persuaded Moira and Wolverine of their freedom, to be more responsible of their acts. Something like the usual trick of free will. What’s important is the illusion of it, not the actual existence. And for someone who’s about to exit the material plane, this seems quite linear. It would be instead absurd to believe Wolverine somehow surprised the Librarian, and still not quite convincing that this was merely a deliberately sacrifice without hidden layers attached.

It’s all about perception, not truth.

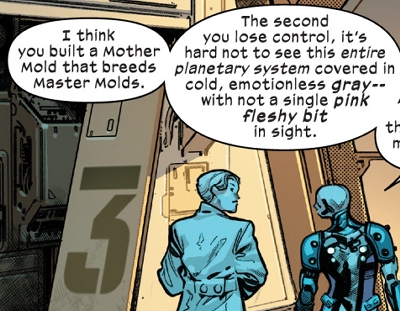

This is where the overall structure is in doubt. The post-human future species is all about shifting consciousness between different kind of shells. That was also their master plan with the Phalanx. Then they have this garden of Eden with a few mutants in it. The mutants inside have no knowledge of the outside, with the exception of Moira and Wolverine, who come from the outside. This is a game of hierarchies of knowledge. Moira and Wolverine are on a higher level, compared to the other mutants in the “cage” with them, but on the other hand they are on a lower level compared to the Librarian.

The Librarian is like the High Evolutionary in the sense he seems to have these “theme parks” (yes, Westworld). Why not more than one? The moment you can meddle with perception, is the moment you can meddle with reality. A game of simulations. If you are uncertain about the future, then the best option is to observe it. To observe future outcomes. And of course it works much better if those observed aren’t aware that they are being observed.

The Librarian essentially says: “We don’t want you to know we know.” Creating the premise for freedom, or agency, the perception of freedom.

But there’s also another way to interpret this, that is also quite intriguing. There’s a lot of talk about mutants being a “natural occurrence.” Or, “an evolutionary response to an environment.” As if saying that, given an environment, the mutant genes represent the most effective adaptation.

So… This goes back to what I just said about the Librarian. In that case, imagine about observing a problem without any necessary prejudice or bias. Who should win a vote, Trump or Clinton? Instead of choosing, you simply set up a simulation and observe the outcomes. There’s going to be no bias outside of the choice of the more preferable between the two ends.

But what happens instead with mutants, even within the reference given by the Librarian? The main trait of mutants is that they are oppressed. That, as Moira repeats again and again afterwards, they always lose. As an evolutionary response… it seems quite bad.

What if instead Moira’s special case isn’t about a “random” mutant power that pops up, but a specifically selected kind of power to achieve the best performance? From the evolutionary perspective that’s exactly what Moira is. A power whose specific function is to accelerate the path. Moira can essentially sample and cycle through timelines, so that she never really loses time. Mutants are oppressed and fail? Then the evolutionary response is to accelerate the process, rebooting timelines until the proper recipe is found. If Mutants faced a block, an hostile environment, the mutant power eventually finds a way. And the way was to “accelerate” by making Moira progress and reset through various cycles. It’s the perfect, ultimate adaptation so that mutants eventually break through.

Moira is the perfect mutant algorithm, the one that keeps endlessly cycling until a solution is found. It is either successful, or endless. It never accepts failure as an answer.

If humans evolved to merely extend their possibilities, through the use and integration of machines, the mutant gene was more incisive in the sense it is aimed at the mechanism itself.

But what if instead Moira was created? Because it all leads there. These evolutionary overlords pretending their hand is hidden. Playing with puppets behind the scenes.

The Librarian does his best to persuade Moira the world is all about her. There was a lingering question: what happens when Moira dies and goes back? What happens to that old timeline? It keeps going, or what? Does the world end if Moira dies? Or we’re looking at “many worlds” kind of interpretation? The Librarian explicitly states (or wants Moira to believe) that Moira “annihilates” time. She’s special in the sense she’s really an instrument of evolution. A way to endlessly cycle solutions until one is found.

So if we want to believe this, then it’s all about knowledge. If the Librarian is killed by Wolverine, and if he’s the only one aware of what Moira can do (why is he, anyway? he says he knows because he observed, but how can he observe the annihilation of time and the death of Moira…?), then no information about that will ever reach the hive mind, because there’s no parallel world where that knowledge reached its destination. Moira instead brings knowledge of the hive mind with her. So she knows something the hive mind does not: she sits higher on the hierarchy.

What’s then interesting is to notice that Moira’s answer to all this isn’t about directly going to House of X. If what we saw is her sixth life, we can go check what happens right after, and see that her attempts are rather aimless. In the seventh she goes on her own against the sentinels, but doesn’t make much progress. In the eighth she tries with Magneto, in the ninth with Apocalypse, and only in the tenth we have what we know. She tries with everyone (and Xavier again). It’s odd because the tenth life all pivots around Krakoa, and it is hinted that it was again the Librarian to suggest something about the flowers.

The Librarian pointed at the path. He played the Godgame.

That scene with Wolverine killing the Librarian looks a lot like the ending of the first season of Westworld.

At the end not much is resolved. Now they go straight into a series of #1s, and I suppose they’ll normalize the story. I doubt we’ll get relevant answers soon.

To see where it’s all going requires looking back. We now know the far future was the past, but what about the rest? In Powers of X #3 we’ve seen how Moira dies in her ninth life, the one leading to House of X. This death was required to obtain data on Nimrod’s origin. So, if we go back to Powers of X #1 we can reinterpret the time blocks so that (X0) should be essentially the tenth life of Moira, before House of X, (X1) is certainly the “current” time, and again 10th Moira. But then we know that (X2), 100 years in the future, is Moira’s 9th. Ending with Wolverine sending Moira to her 10th with information on how to prevent Nimrod (there’s a nice touch if you go back to that scene, as Moira anticipates what Wolverine is going to say, since for her it’s the second time it happens…). And now we know that (X3), 1.000 years in the future, was actually Moira’s 6th.

(but then isn’t it kind of weird that the flowers were already being used during Moira’s 9th? So Krakoa definitely isn’t something new that only comes up in 10th… so also not Xavier’s idea. Moira’s 9th is the alliance with Apocalypse that… makes sense considering his connection to the island…)

Meaning we’ve seen a whole lot of nothing about the future. Those future days came from the past.