Here we are again.

Ted Chiang has recently released a new short stories collection, and within it he has repackaged and repurposed the exact same faulty concept of time and free will. The difference is that it has been pared down to just ONE page, so it’s all the more easy to handle (and debunk).

I’m referring to the story with the title “What’s Expected of Us”. I haven’t read more than that, and I’m also discouraged for doing so.

I’m sorry but I can’t take Chiang seriously anymore, and I can’t take seriously anyone who considers him a decent writer, either. You cannot drag an idea for so long without noticing how deeply faulty it is, and keep preaching as if it’s gospel. Okay that you dressed it up nicely in “Story of Your Life”, but here it’s stark naked, and I’m astonished that you have no shame showing it.

I’ve written a few comments recently about Dark and its bootstrap paradox. And even this short story by Chiang is a variation on the same theme, and generally amounts to a simplification of the more interesting and articulated Newcomb’s Paradox. This just to reiterate there’s nothing new under the sun, just another coat of obfuscation by Chiang, that for some inexplicable reason people seem to mistake for insight and great sci-fi.

The concept here is a “Predictor”, that is just a basic box with a button and a light. The premise is that free will doesn’t exist, and the predictor works by flashing the light one second before someone will press the button. The device being of course infallible.

Let’s start here: I absolutely accept the premise. The premise no free will exists, and human behavior can be deterministically predicted with absolute accuracy by this device.

The real problem isn’t determinism and free will, the problem is that Chiang makes this device operate in a completely dishonest way, in order to HIDE and dissemble the magical trick it is based on. This is what he writes to describe the practical use of the device:

But when you try to break the rules, you find that you can’t. If you try to press the button without having seen a flash, the flash immediately appears, and no matter how fast you move, you never push the button until a second has elapsed. If you wait for the flash, intending to keep from pressing the button afterward, the flash never appears. No matter what you do, the light always precedes the button press. There’s no way to fool a Predictor.

The first example doesn’t seem very plausible. The idea is you’re trying to press the button as fast as possible, but “the flash immediately appears”. It still takes a whole second, so the thesis is that you cannot press a single button faster than a whole second. And that’s already hubris, but let’s move on.

The second example is more interesting because it actually describes what it would REALLY happen if such device existed: you want to fool the device, so you wait for the light just so you WON’T press the button. And the consequence of this “deliberate choice” is, correctly, that the flash never appears.

This example is more interesting because it reveals something hidden. If the predictor never makes a prediction, then it can never been proven wrong. The device correctly functions by avoiding the one state that would compromise its function, by proving the prediction wrong. Without a prediction there’s no possible confutation. This is just like saying you cannot disprove something that doesn’t exist (argument from ignorance or variations).

The solution to this is to avoid this dishonest way of shaping the conundrum that Chiang uses, and instead see what happens if the prediction is FORCED (instead of evaded), so that it can be appropriately tested.

“Most people agree these arguments are irrefutable, but no one ever really accepts the conclusion. What it takes is a demonstration, and that’s what a Predictor provides.”

And that’s exactly what I’ll do: demonstrate that Chiang’s concept is logically faulty and produced by misleading premises. To do this I’ll create an experiment, just like what Chiang did in the story, with a few variations so that I can properly test the predictor with the sensible data.

As I said, this has nothing to do with free will and determinism, so I can prove the fallacy by removing even more variables. Instead of predicting human behavior I just need the predictor to be connected to a computer, and still prove that it will fail. The predictor simply has to predict whether on a screen the letter A or the letter B will be shown. The basic function of the predictor is the same as in the story (“it sends a signal back in time”). So the predictor sees which letter is shown on screen, in the future, and sends it back in time the result for the prediction.

The new trick in this experiment is that the computer that executes the process that will show either the letter A or the letter B on screen, takes the predictor’s prediction as INPUT. So that if the predictor predicts that the letter A will be shown, then the computer will display the letter B on screen, effectively contradicting the prediction. No matter what the predictor predicts, the process is built to contradict it.

In every single case possible the prediction is going to be invalidated. Hence, the logical fallacy that is at the core of Chiang’s concept. There isn’t even a single case to make this work, and the reason is exactly because of the logical fallacy.

Explanation: what happens in this example/experiment is that the moment when the prediction is sent back in time, that information is new information that alters the global state of the system, and so shifting it to a new, different state. It’s not that the predictor “doesn’t work”, it’s that every hypothetical prediction that is made triggers a change of state of the system.

For a better comprehension: the problem here isn’t again about the plausibility of determinism, and so the possibility of prediction. Predicting the behavior of a deterministic system is of course logically possible. The real problem we have here isn’t about determinism and it isn’t about prediction either. It’s INSTEAD about a process built on self-reference and recursion. The prediction here informs the system it tries to predict, and doing so recursively alters itself. We can imagine to ideally get to the end of this process, as if hammering down these time loops in their ultimate state, when all it’s done. But the point is that the process we are observing is one of infinite regression. So that it never closes, and so that, without a closure, can’t be predicted. Unless the prediction is itself separated from the system, without informing it directly and without triggering the self-reference.

This works EXACTLY like the liar’s paradox. In this well known example we have a phrase that alternates between two states, true and false, that recursively feed on themselves, with self-reference, so that they endlessly shift between those two positions. Until human beings observe and heuristically classify this as a “paradox”. It’s not, accurately, a paradox, it’s just a recursive, self-referential system without closure, and so we make up our own human simplification by assuming that a system without a closure “doesn’t make sense”, and so it’s a paradox. Something that cannot be hammered down logically in a fixed position, since it’s built to shift endlessly.

So, you can predict the evolution of a deterministic system where the prediction itself is separated from the system being predicted. But you CANNOT create a self-reference within the system without facing the consequences. That self-reference recursively altering the behavior, triggering an infinite regression that, by avoiding closure, makes the prediction impossible too, since the idea of a prediction implies that the system being predicted assumes some fixed final state that can be mapped.

This is also the reason why what Chiang writes next is even more absurd and ill informed:

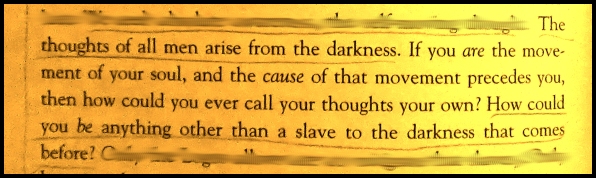

“People used to speculate about a thought that destroys the thinker, some unspeakable Lovecraftian horror, or a Gödel sentence that crashes the human logical system. It turns out that the disabling thought is one that we’ve all encountered: the idea that free will doesn’t exist. It just wasn’t harmful until you believed it.”

This is just magical thinking: the idea that a “belief” can trigger some special, unprecedented effect. This happens just as consequence of the logical fallacy at the foundation of the whole concept. What actually DOES happen is that a logical system “cannot crash”. Because it’s built on logic, it observes and operates on logic, and whatever hypothesis of something non-logical would be simply unseen by such a system. And if something is unseen and unperceived, it doesn’t exist. It never becomes experience. It never enters or even interacts with the environment (hence we pass the threshold and step into pure metaphysics, that Chiang obviously can’t deal with, being blind to what he’s observing).

The idea that “free will doesn’t exist” is locked off, out of experience. Because you cannot become aware of something embedded. The awareness of lack of free will doesn’t bestow free will, so it produces no change at all. No emancipation.

Chiang continues tripping on this, since he started from a faulty proposition:

“My message to you is this: Pretend that you have free will. It’s essential that you behave as if your decisions matter, even though you know they don’t. The reality isn’t important; what’s important is your belief, and believing the lie is the only way to avoid a waking coma.”

The truth is the exact opposite of what he says here. Nothing is “essential”, and especially “your belief” is completely irrelevant. The truth is that there’s no escape from this system, so no matter what you believe, the result is immutable.

He partially admits it in the following paragraph:

“There’s nothing anyone can do about it”

So, logically, it’s really not important what you “believe”, because beliefs aren’t magical, they aren’t transcendental, and so they cannot help in any way out of this process. What you believe is irrelevant.

The opposite is true: you have no freedom to exit the belief in free will, because you cannot act on the premise of the absence of it. You cannot be exempted from what we can generally call the “human condition”, and the human condition is built around the *perception* of free will. Whether this perception is fundamentally and truthfully “free” or just an illusion, is irrelevant, because we are chained to this state, and its truth-ness or false-ness are both unverifiable and with no consequence. Hence they do not exist (we can assume “as if” they don’t, since it’s indifferent relative to our present state, as good epistemology would dictate).

Human beings are structurally chained to free will, because the nature of human beings is perspectival, partial. Caged within the system that builds them. In a similar way, you cannot predict determinism from within the system you’re trying to predict. Free will, like determinism, can only be factually proven by exiting the system (of reality). Until we remain caged within, we continue to submit to (perception of) free will, and the nature of self reference that doesn’t allow closure and so accurate, complete prediction (as to say: the Laplacian demon can only exist outside the system it is observing, otherwise it’s also bound to self-refence and incompleteness/non-closure).

That said, not all bootstrap paradoxes are logically faulty. I always thought that Wittgenstein’s Tractatus is a form of metaphorical, and logically valid, bootstrap paradox. There are ways to hide the origin, that’s the trick. Not so much, as in Dark, that origins don’t exist. But there can be patterns where origins could be “missed”, or unperceived. Unseen. There are ways for the world to “fall off” from its root, and so appear as if suspended. Independent. Just like consciousness.

It’s all about perception… and truth. Because so, if we value truth, we cannot value Ted Chiang, whose work is like that of an illusionist who tries to obfuscate so much more than reveal. Appearing to be smart and deep through the use of misleading intuition pumps.

EDIT: After writing this I searched online for other comments about this specific story and found one in particular that matches mine but that more directly ties with the example of the story:

“Consider the Free Will Device, put next to the predictor. Free Will Device is actually entirely deterministic, and doesn’t have any free will of its own. It consist of photocell which watches the LED on predictor, timer, which gets reset to 0 every time light hits photocell, and actuator which pushes the button when timer reaches 2 seconds. If predictor blinks within those 2 seconds, there won’t be a button press, and if predictor doesn’t blink, there will be a button press.”

EDIT2: I noticed later that the story here is from 2005, so I now have no idea if it pre-dates Arrival or whatever. But maybe Ted Chiang could be forgiven for dredging up some faulty old story. Still, this is Ron Hubbard type of quality, and so it’s fairly condemnable for its poor philosophy, regardless of when it was written.