I had this project (of sort) for a very long time so I simply decided that I needed to start or it would be one of those things endlessly delayed.

One good reason for NOT doing it is that my knowledge of Philip K. Dick is rather poor, and the Exegesis is filled with interpretations of Dick’s own body of work. It’s a “meta” self-analysis of his life and everything he wrote. So the Exegesis should come AFTER you read and understood everything else, and are ready for Dick own further insight. It’s the last station. But reading all of his production, or even a meaningful portion, would be already a giant project that would be almost without end by itself (with my current realistic pacing, of course). So the Exegesis was just this long term goal that only kept moving further and further away.

The choice was simply to go straight to the deep end. A long time ago I read a number of short stories, some of which I still remember quite well. I also read Ubik but remember almost nothing about it. More recently I read “The Man in the High Castle”, and I thought it was especially good. It had a somewhat “literary” flavor, not pulpy at all, it might have been maybe a weird bias because I read it on a pristine copy of the Library of America collection.

My attention when reading the book was all on the language. I felt as if there was this other layer, separate from the story, where the lines of text had a more abstract and general meaning. Not quite there. By the end of the book it was like I was on a very private journey, as if I wasn’t sure that what I was reading was really what was expected. Now I just don’t know how accurate my experience of this book was. I was somewhat distracted, looking at other things, highlighting parts of the book and taking them out of context, to run off with concepts, away from the story and characters.

I probably understood very little of that book, in a “traditional” way.

This will inform my experience of the Exegesis. I’ve got a plan, I know what to do and how. You can take the Exegesis like the convoluted speculations of someone caught in a loop of mental illness, and that’s probably the most accurate conclusion. I don’t expect to find any sort of “revelation” in a transcendental sense, actually I’m absolutely certain of this. I’m not chasing after mystical influences. I’m not a believer and there’s zero chances of me becoming one, unless I end up losing my mind as well. I guess.

But at the same time I’m going to take the Exegesis SERIOUSLY. Because I take everything seriously. I’m not here to judge. I’m not here to “diagnose” Dick, I’m not a doctor, I know almost nothing of mental illness, so I’m not going to look for an “explanation” for what he was feeling and writing. I will treat this as a sort of mythology, and I’ll follow James Hillman’s idea of “sticking with the image” (speaking of dreams and interpretations). Taken straight form the wikipedia:

the moment you’ve defined the snake, interpreted it, you’ve lost the snake, you’ve stopped it and the person leaves the hour with a concept about my repressed sexuality or my cold black passions … and you’ve lost the snake. The task of analysis is to keep the snake there, the black snake…see, the black snake’s no longer necessary the moment it’s been interpreted, and you don’t need your dreams any more because they’ve been interpreted.

What I’ll try to do with the Exegesis is… dig deeper. I want to look for deeper patterns. The deep end of the madness, the potential. The symbols, the myths. It should be a journey, not a judgement. (and yet I’ll also have to understand, how I understand)

At the same time, how can I pretend of being able to dig deeper, with what knowledge? From what privileged position? Well, that’s why this is a deliberate “eisegesis”, meaning that, as I was doing for The Man in the High Castle, this is a personal journey where I will dig in the direction I choose. Eisegesis means I’ll read into the Exegesis whatever I want to find, whatever I think I see, but without any pretense of being faithful to Dick himself, without an objective goal or insight.

Then again, I CAN read the Exegesis. Because I’m not floatsam. My own philosophical and scientific concepts of the world, and metaphysics in general, are now very well grounded, very well structured. I come to this project with a well organized mind, with a solid framework that generally helps me a lot. A kind of reliable compass that I can use to orient myself in the most alien of terrains. And I am rational and sometimes cynical, so on one side I’m certainly not putting myself on a pedestal, but I won’t do this with Dick either.

I’m not coming to the Exegesis thinking it will be an extraordinary and revelatory work of a mad genius. But I expect it being food for the mind. The life of the mind.

I was forgetting the important part:

I’ve bought, years ago now, the hardcover edition of the published portion of the Exegesis but my project doesn’t stop there. I’ve also scoured the internet for all the material I could find, including the original scans and a good total amount of stuff that isn’t part of the published book. I made a rough count of all I got and it’s a grand total of 6500 pages. According to various estimates the original whole thing should be 8000+ pages, so it certainly isn’t complete. I’ve read estimates all over the place, like the published book being only 1/10 of the total. This doesn’t seem true. A page scribbled by Dick usually just takes half a page or so, of the published book. I know the published total is about 360k words. The book itself goes from page 1 to 900, so maybe it’s closer to 1/5 or 1/6 of the total. And then I have the rest of the material. So, maybe, closer to 3/4 of the total.

The quality of the material available is all over the place. It goes from typed pages:

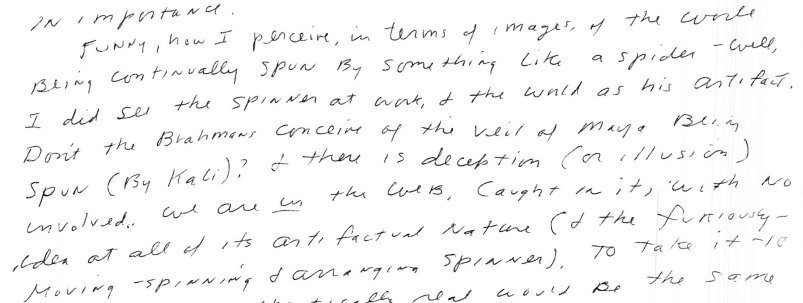

To somewhat readable handwriting:

To badly scanned and sketchy mess like this (and not the worst example):

Some of these have already been transcribed, but a lot of the material done overlaps with the book. I’m going to use everything, the book, the online transcriptions, and then even doing my best to extricate meaning from the handwritten pages, with variable levels of success, I guess. But I’ll try.