The first 100 pages of the Thomas Covenant series were the very last thing in the fantasy genre I read almost 10 years ago. I enjoyed what I read, even if not particularly so, then I couldn’t find anymore the book for various reasons and I abandoned entirely the genre only to return to it in the last years. These days I had no particular interest in going back and read it (while Donaldson’s GAP series is part of my ever expanding reading queue) but it became a resolution when I read that Donaldson finished writing the first draft of “The Last Dark”, the fourth and last book in the third series.

I’ve started reading Thomas Covenant from the very beginning because I’m interested in what he’s doing right at the end. I’m ready to go through the first million of words in order to get there. If this third series never came out I’d have probably never had again the interest to go back and read what I missed, but knowing that he returned once again to it, more than twenty years later, makes me curious about what places he may go and what he’ll bring along of all these years. This series of 3 + 3 + 4 books was never planned as so. When he wrote the first trilogy it was “done”, nothing else required or planned. Then he found ideas and wrote a second trilogy, which probably exists also as a dialogue with the first, but it was again a thing on its own, closed. Now he returns. I have trust in him when he says that every time he returns the stakes and ambition rise, and I want to read this because I’m interested on where it all leads.

I’m almost halfway though the first book and should be able to write down more comments soon after I’m done with Midnight Tides. Curiously enough the controversial parts of “Lord Foul’s Bane” are the strongest. My interest is held entirely by what I usually see criticized, while the more traditional and fantastic part of the journey through the land feels dull and slow.

The rape scene is probably the most discussed and criticized part of the book and yet I had no problems with it. It’s a strong scene that is perfectly excused by the context, I don’t see anything in it that feels forced or indulgent. I’d rather say that it’s one of the sporadic points that make the book worthwhile. It’s not about being edgy and subverting some canons by shocking the reader, I don’t see a “writer’s intent” in it, as if in showing a purpose, a declaration of tones and themes so the reader knows what he’s going to find in the book. The scene is not there to set a bleak mood or warn the reader. It is there because there’s no way around. It’s the consequence of what is going on.

This leads to the other aspect about it: Thomas Covenant, the Unbeliever. From a side it’s kind of curious how the “unbelief” of the character seems carried over (or “in”) the context. Fantasy is not serious literature, you can’t believe it. So here’s a book about a guy who finds himself in a fantasy world and… does not believe it. Literally. The other side of this argument is that the “Unbeliever” is the leading theme, embedded with it is also the rape scene and why it fits with the rest. Thomas is convinced of going through a vivid and elaborate dream. He knows he was hit by a car and now he’s hallucinating and fighting to survive. In this dream he goes through a reawakening of spirit and senses, but it is painful because he is aware it’s all fake. The more beautiful the world, the most cruel it is, because it all shows him a beauty he knows he’ll lose as soon he wakes up from this terrible hallucination. Hence the rape. He rapes Lena because Lena, to his eyes, taunts him. She speaks and moves with cruelty (but this is partially concealed to the reader). Being part of HIS dream he has all the rights to react to all this with rage. One thing I noticed while reading is that Thomas goes through a lot of states internally but communicates little of it on the outside. More than “characterization” this is the result of awareness. He does not believe in the “world”, so talking to it is kind of stupid. Does it make sense talking to your own dreams? Aren’t the dream-shapes there just to mock and play with you? This is also mirrored by the reactions of some people to him. They believe he knows, but is faking his lack of knowledge of the world because he’s testing them.

So Thomas Covenant is character locked in. The introspection is the point since he doesn’t believe in the external world. The “rape” is an accusation toward the outside. It holds on many levels. It’s even a crime if you rape someone in a dream? It is a crime if the rape was not deliberate? Donaldson, the writer, plays with all this. And this is what interests me deeply, the bold links between internal/external, between writer and character, the fantasy and the Fantasy.

Obviously I can’t avoid now to interpret all this my own way. Probably most readers were in for the Fantasy, for The Land and its weird creatures. I’m in entirely to interpret it symbolically, and that’s where the book carries some value for me. Yesterday I read a part that felt like a reference to The Matrix. Thomas Covenant and The Matrix? What should they have in common?

This:

Foamfollower stood in the stern, facing upstream, with the high tiller under his left arm and his right held up to the river breezes; and he was chanting something, some plainsong ,in a language Covenant could not understand- a song with a wave-breaking, salty timbre like the taste of the sea. For a moment after Covenant’s question, he kept up his rolling chant. But soon its language changed, and Covenant heard him sing:

Stone and Sea are deep in life,

two unalterable symbols of the world:

permanence at rest, and permanence in motion;

participants in the Power that remains.

a song with a wave-breaking, salty timbre like the taste of the sea. Think about it, how can a song have a “salty” timbre? This made me think of a world (The Land) made of language (so words, numbers). This Foamfollower is a giant whose boat moves upriver. It’s a “spell”, something breaking the natural rules. And it comes from language he uses. I don’t know how far Donaldson consciously pushes this, but it’s there.

I just can’t avoid reading this book in a sort of Kabbalist way. The whole journey is “symbolic”. I don’t know how Donaldson resolves it, but at the moment I buy into the “hallucination”, so Thomas is moving through an internal landscape. This doesn’t even need to be a “suspect” of a writing intent, because it just can’t be avoided. Donaldson HAS TO write an internal landscape, because The Land does not exist. So whether you see it as a contradiction or proper form, it is brought in the book as it is in reality. You can’t escape it, and it is what makes the book strong.

Within this context it is particularly interesting to see how Donaldson deals with the “cosmology”. “The Celebration of Spring” is a chapter he said he dreamed and he wrote exactly as it came to him. It’s about a circular dance of some flame figures that kinda fits with a Kabbalist interpretation. In another scene the giant talks about a legend on the cosmology. Most of it is formulaic and not really addressing the interesting points (there’s always a Creator that creates, but somehow some kind of flaw slips through and acquires its own deliberateness, threatening the rest), but it is good for the mirror it creates.

Essentially the giant compares the creation of the world with the legendary history of his own race. Both stranded from home. Locked away from their proper place and unable to return. Taken from within, it is interesting because you wonder whether they built their creation myth on the basis of their own history (so projecting “outside” what happened to them for real, shaping gods in their forms) or if it’s the opposite, that they wrote their own legendary history shaped around a myth that they received (if you believe in-world holiness). Ambivalent. And it all again fits with certain Kabbalistic forms, since this idea of being separated and then cut from “home” is essentially the Kabbalistic structure of men stranded in the physical world. The barrier between the physical and the concealed spirituality.

All of it then brought in the book at another level, since Thomas Covenant is also stranded and cut away from home, being trapped in this fantasy world. This game of mirrors, where the same structure repeats at different levels, is one of the truly inspired parts of the book. Sometimes it slides back into fantasy conventions (for example I think the dialogue between Thomas and Lord Foul when the two of them meet at the very beginning is dreadful) but overall I’m enjoying what I’m reading and find now things that I’d likely have missed ten years ago.

I don’t read many mangas these days but I make exceptions for those masterpieces that set themselves apart. There are certain signature works in every medium and genre, Homunculus isn’t very much “signature” because it doesn’t seem to represent any canon, but it sets itself apart as one of those rare, significant works. It is a true masterpiece, of the kind you can count on your hands. I’m writing about it also because it’s finally complete. It’s 15 volumes, the last one came out in Japan in April 2011 and

I don’t read many mangas these days but I make exceptions for those masterpieces that set themselves apart. There are certain signature works in every medium and genre, Homunculus isn’t very much “signature” because it doesn’t seem to represent any canon, but it sets itself apart as one of those rare, significant works. It is a true masterpiece, of the kind you can count on your hands. I’m writing about it also because it’s finally complete. It’s 15 volumes, the last one came out in Japan in April 2011 and

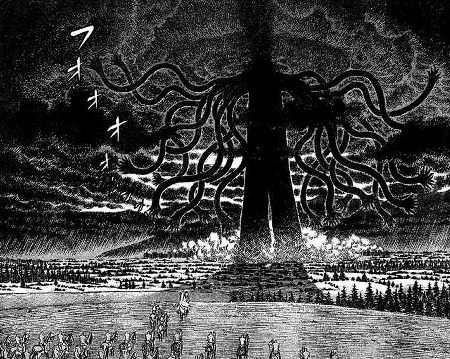

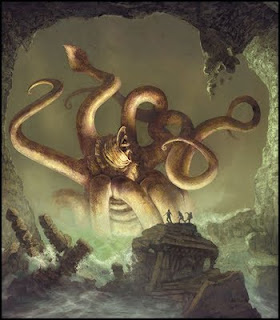

I’ve reached a point in the book where some big sea god makes its grand entrance. I was quite in awe and decided to write a bit about it, about how I perceived the whole scene and wanted it to be more than how it appears in the book. It has quite an evocative power but I feel that Erikson understated way too much such a grandiose event. It’s one awesome idea Erikson had, but that is dismissed in the multitude of other things. Other writers could have made this a dramatic pivot of a novel, but here it is somewhat resolved in three pages or so. 3-4 pages enough to introduce the threat posed by this unknown sea god, research its mystery, see it rise on the surface wrecking chaos, conclude the first battle and solve a first mystery. Too fast!

I’ve reached a point in the book where some big sea god makes its grand entrance. I was quite in awe and decided to write a bit about it, about how I perceived the whole scene and wanted it to be more than how it appears in the book. It has quite an evocative power but I feel that Erikson understated way too much such a grandiose event. It’s one awesome idea Erikson had, but that is dismissed in the multitude of other things. Other writers could have made this a dramatic pivot of a novel, but here it is somewhat resolved in three pages or so. 3-4 pages enough to introduce the threat posed by this unknown sea god, research its mystery, see it rise on the surface wrecking chaos, conclude the first battle and solve a first mystery. Too fast!