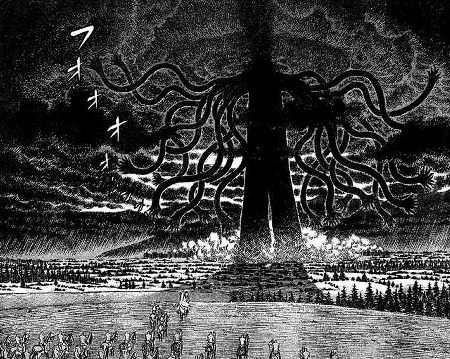

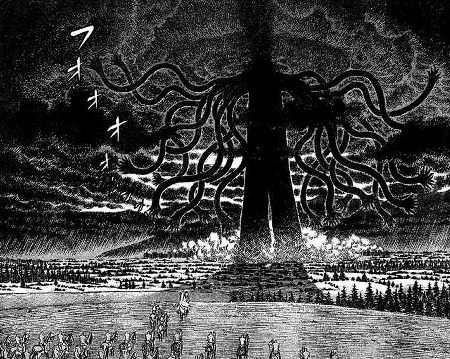

I’ve reached a point in the book where some big sea god makes its grand entrance. I was quite in awe and decided to write a bit about it, about how I perceived the whole scene and wanted it to be more than how it appears in the book. It has quite an evocative power but I feel that Erikson understated way too much such a grandiose event. It’s one awesome idea Erikson had, but that is dismissed in the multitude of other things. Other writers could have made this a dramatic pivot of a novel, but here it is somewhat resolved in three pages or so. 3-4 pages enough to introduce the threat posed by this unknown sea god, research its mystery, see it rise on the surface wrecking chaos, conclude the first battle and solve a first mystery. Too fast!

I’ve reached a point in the book where some big sea god makes its grand entrance. I was quite in awe and decided to write a bit about it, about how I perceived the whole scene and wanted it to be more than how it appears in the book. It has quite an evocative power but I feel that Erikson understated way too much such a grandiose event. It’s one awesome idea Erikson had, but that is dismissed in the multitude of other things. Other writers could have made this a dramatic pivot of a novel, but here it is somewhat resolved in three pages or so. 3-4 pages enough to introduce the threat posed by this unknown sea god, research its mystery, see it rise on the surface wrecking chaos, conclude the first battle and solve a first mystery. Too fast!

Embedded in those three pages there isn’t just that, but a treasure of fundamental ideas that go deep down. Even if so understated they still make a fulcrum of things. So I’m going to describe what I saw, in there, knowing it’s not going to be perfectly accurate, but not my own fancy either.

When I was a kid Lovecraft was my myth. I couldn’t get E. A. Poe because he was too psychological, but Lovecraft delivered fully what I wanted. He grasped the psychological side, but at the same time also going all the way with awe-inspiring imagery. Fantastic, otherworldly landscapes, truly alien creatures. He didn’t underplay the fantastic element. Today looking at Lovecraftian mythology it all seems quite thin. Lovecraft is about atmosphere, what it suggests. Under that surface there’s chaos and uncertainty that feed on the idea of “cosmic horror”. It’s a powerful feeling, part of the unconscious and dream world, but it is abstract and undifferentiated.

The implicit rule is that when you reveal a mystery, describe how it operates, how it works internally and externally, you defuse all its power. So if Lovecraft probed and replaced the void of the “cosmic horror” with something precise, then all the magic and evocative power would be lost. The magic is about not seeing completely, the horror of the unknown, something right out the corner of the eye. And so we get a tradition of Horror where we don’t quite see, something only suggested, vaguely hinted at, the monster is a shadow, an outline.

Erikson instead, striving for other goals, goes deep into the mystery, and instead of diminishing its power he manages to not “explaining it away”, but make it stronger and even more evocative and full of implications than ever! The danger down this path is evident if you for example watched LOST, the more the mystery was revealed the more it got broken, made no sense, felt more and more contrived and annoying. In less words: the answers to mysteries weren’t satisfying. They weren’t reaching as high as the expectations. Here instead we have an occasion to see how it can become satisfying.

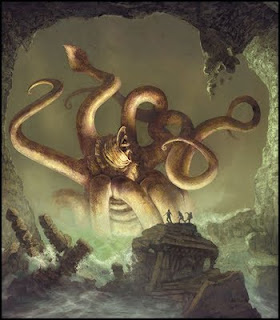

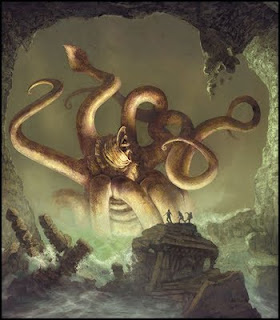

In the book a character starts to analyze the situation and the possible origin of this sea god that is looming and threatening his army. He comes out with three possibilities (two in the book, that’s one of the reasons why I say Erikson underplayed this too much). The first is that in this region, possibly thousands of years before, there was another population. It is explained that the land was made of limestone and, due to underground rivers and currents, the ground was eroded and shaped, and some deep, circular natural pits were formed. This population used one of these huge pits as a sacred place to their own deity. They threw into this pit bones, living sacrifices and other precious materials, till it filled up. So the sea god they are facing in current times is what this ancient population worshiped thousands of years before. The second hypothesis is that there was no original god that fed on that pit, but that another spirit or god was lured by the sacrifices, it disguised itself as their god, it became and replaced their god (and this is a pattern that returns in these books, gods that deceive and manipulate, preying onto the delusion of common people), and so its power grew and grew.

The third hypothesis is that there was… nothing. This is the most fascinating one because it took me a while to come to terms with it in these books. (opening necessary parenthesis here) One usually assumes that a god either exists or not. We either believe or we don’t. In a Fantasy novel, where gods are “tangible” and real, you assume there are no problems of faith. Gods exist, and that’s all. Yet, Erikson’s mythology is “protean”. Meaning that it is “fluid”. It’s a bit counter intuitive but let’s say that there could be some people that have their own pantheon. These gods exist and are real. Yet it’s entirely possible that on another continent there’s a different population with a completely different belief system and pantheon. They believe in different things and so their gods are different, but STILL very real. Belief, in our real world, is also protean, because it is created and is transformed. What a Christian believes is not what a Native American believes. In the Malazan world the “conceit” is that the mechanics are the same as our real world, but the gods come into being. Are made. So, going back to this third hypothesis, this means that a god may have come out of some, let’s say, “emotive or symbolic power”. The accumulation of lives sacrificed to some conceptual deity, the value of the symbols (the precious materials also thrown in the pit), all coalesced over time into something. “A creature came into being, and was taught the nature of hunger, of desire. Made into an addict of blood and grief and terror.”

Now take all these three possibilities and you’ll see that all three have significant implications. In the context the characters are preparing to fight this god in battle, so they need to learn as much as they can about it. What it is, what it can do. In the first case (a native, ancient god) the mystery becomes about what kind of god the ancient population worshiped. What its nature may be. In the second case (a spirit or a god that was attracted by sacrifices) the mystery deepens, because the ancient god is a mask and anything could have taken that position, hidden within, with its own motives and goals. What kind of creature was it? Was it maybe some other god or ancient creature? Where does it come from? What’s its true origin? Then the third case (a god was “fashioned”, from nothing), how do you fight something that is not there?

See, the mystery GROWS. It becomes filled with interesting implications, and consequences because in the context there’s a war ahead and this god is being used in it. Among all this, Erikson deepens the “import”. This is where I love what he does. It’s a fantasy story, but it has no power, no weight, if it doesn’t try to reach deep and say something that isn’t merely a clever “invention”. Take this quote:

Shorelines were places of worship the world over. The earliest records surviving from the First Empire made note of that again and again among peoples encountered during the explorations. The verge between sea and land marked the manifestation of the symbolic transition between the known and the unknown. Between life and death, spirit and mind, between an unlimited host of elements and forces contrary yet locked together. Lives were given to the seas, treasures were flung into their depths. And, upon the waters themselves, ships and their crews were dragged into the deep time and again.

Here Erikson, in a few lines, evokes a whole breadth of literature. Man and sea. All contained within that idea, then developed and shaped, “fashioned” in a myriad of stories. Thousands of books, movies, poetry, music. Ancient and modern. A theme that runs through this book, Midnight Tides, confirming that what I see in the title (the undercurrent, the subconscious, what’s hidden and unseen below the sea level) was not an illusion, but something that Erikson grasped fully (see also this and the quote about erosion).

The mythological work done in these three pages (btw, I already surpassed the wordcount of the whole scene I’m writing about, which also includes the battle itself, just saying) is not complete. The analysis continues speculating on the fact that this god should be dead.

The spirit was doomed, and should have eventually died. Had not the seas risen to swallow the land, had not its world’s walls suddenly vanished, releasing it to all that lay beyond.

The ancient population that filled the pit with gifts and sacrifices vanished at some point. Maybe they migrated somewhere else, or managed to destroy themselves (it wouldn’t be the first time in this setting). In both cases the god would be still bound to the pit, and, with the population feeding it gone, it would weaken and eventually die. Yet this was not a weakened creature, quite the contrary. What happened? That the whole land, including this pit, was in origin dry. At some point the level of the ocean rose (and this is likely as consequence of another cataclysmic event part of the mythology, opening new questions, possibly answers) and the land was submerged. Symbolically (see the quote above) and concretely, this means that the god was unbound, passed through the threshold between land and sea, known and unknown. It got unleashed onto possibilities. And unbound from the tie with its worshipers, it also got a sort of freedom. Out in the ocean ships sailed, more wars, more deaths, more to feed on. But outside of its pit survival wasn’t easy.

For all that, the spirit had known… competition. And, Nekal Bara suspected, had fared poorly. Weakened, suffering, it had returned to its hole, there beneath the deluge. Returned to die.

There was no way of knowing how the Tiste Edur warlocks had found it, or came to understand its nature and the potential within it. But they had bound it, fed it blood until its strength returned, and it had grown, and with that growth, a burgeoning hunger.

And so it rises again and is used as a tool in a war. Again and again in this series the past returns, sometime as it was, sometime disguised, manipulating and manipulated. Erikson already dealt with this sort of Lovecraftian mythology in Memories of Ice (I’m referring to the Matron buried under the plain), where he made real a line by Lovecraft I only remember in Italian, that retranslated sounds like this: It is not dead what forever can wait.

Erikson goes deep into the myth by not treating it merely as a self-serving invention. It feeds on its core, which is the anthropomorphic vision of the world and its coming to terms with reality. As the cover blurb by Glen Cook goes, I also stand slack-jawed in awe of what Erikson is doing. Yet I’ll leave a tiny, little disappointment because I sometimes feel that he doesn’t run all the way with his ideas. As if he didn’t completely believe in their strength. So much and more was contained in those three pages, that ultimately is understated as a small scene buried within a chapter. I haven’t gone further so I don’t know what this creature truly is, but I feel that too much potential was dismissed in a short run-through of hypothesis and even shorter confrontation. Which by the way was confusedly described (has the wizard somewhat shot himself into the creature? how could he see and describe what happens to his partner if one was on top of a lighthouse and the other far at the end of the docks?). I always have a problem of scale with Erikson’s descriptions, sometime he can evoke some huge setpieces filled with sense of wonder, but sometime one doesn’t “feel” this and it seems instead cramped, or not as vast as it could. Visually, it should be given some more “punch”, and it’s again something that doesn’t satisfies me fully. Give me some great imagery when you have motivations and means to do it (and what I wrote here is the foundation to make it happen, having earned it). Erikson’s creatures are sometime lost in the trivial, big dog, big wolf, green eyes. Give me something awe inspiring, huge, that also looks cool. You don’t have a budget on special effects. Ramp up the scale, make something truly grand.

I’m saying this because that’s as far I’ve read and the scene leaves me with that kind of disappointment (after having achieved and deserved all that awe). I don’t know what this creature looks like since it wasn’t shown yet. I don’t know how truly big it is. But from one side it all happened too fast, the prose not giving it enough emphasis and space compared to the rest of the novel. And from another its grandiose visual potential is somewhat lost on a minor PoV, minor battle, minor scene. On a creature that is “big”, but big as a ship or BIG, as a mountain-spanning behemoth of a beast? The writing, for how good it is and how much it packs in the economy of words, runs contrary to what the scene needed, imho.

He disappoints me on the easy parts. Yes Steve, you are too conservative and not enough EPIC.

I don’t read many mangas these days but I make exceptions for those masterpieces that set themselves apart. There are certain signature works in every medium and genre, Homunculus isn’t very much “signature” because it doesn’t seem to represent any canon, but it sets itself apart as one of those rare, significant works. It is a true masterpiece, of the kind you can count on your hands. I’m writing about it also because it’s finally complete. It’s 15 volumes, the last one came out in Japan in April 2011 and

I don’t read many mangas these days but I make exceptions for those masterpieces that set themselves apart. There are certain signature works in every medium and genre, Homunculus isn’t very much “signature” because it doesn’t seem to represent any canon, but it sets itself apart as one of those rare, significant works. It is a true masterpiece, of the kind you can count on your hands. I’m writing about it also because it’s finally complete. It’s 15 volumes, the last one came out in Japan in April 2011 and

I’ve reached a point in the book where some big sea god makes its grand entrance. I was quite in awe and decided to write a bit about it, about how I perceived the whole scene and wanted it to be more than how it appears in the book. It has quite an evocative power but I feel that Erikson understated way too much such a grandiose event. It’s one awesome idea Erikson had, but that is dismissed in the multitude of other things. Other writers could have made this a dramatic pivot of a novel, but here it is somewhat resolved in three pages or so. 3-4 pages enough to introduce the threat posed by this unknown sea god, research its mystery, see it rise on the surface wrecking chaos, conclude the first battle and solve a first mystery. Too fast!

I’ve reached a point in the book where some big sea god makes its grand entrance. I was quite in awe and decided to write a bit about it, about how I perceived the whole scene and wanted it to be more than how it appears in the book. It has quite an evocative power but I feel that Erikson understated way too much such a grandiose event. It’s one awesome idea Erikson had, but that is dismissed in the multitude of other things. Other writers could have made this a dramatic pivot of a novel, but here it is somewhat resolved in three pages or so. 3-4 pages enough to introduce the threat posed by this unknown sea god, research its mystery, see it rise on the surface wrecking chaos, conclude the first battle and solve a first mystery. Too fast!