– Who watches the watchmen?

– How to avoid what’s unavoidable?

– How to kill a god? (not everything that shines, shines)

These are three notes I scribbled down after re-reading Watchmen and watching the TV series. It takes me some effort to go back and remember what I meant at the time… The first is straightforward, the second comes from the comics, the third is from the TV show (third or fourth episode?). All three represent a similar kind of self-referential loop.

The second one is framed by the plot in the comics: there’s a crisis that’s brewing and reaching the tipping point. As in a simple causal system, humanity is driving toward its annihilation. How to avoid this, how to avoid the inevitable? That’s Veidt’s plan.

The third comes from a weird metaphysical story told by Laurie in a phone booth. You can interpret the story narratively, since each character in that story is meant to represent those classic Watchmen characters and their moral conundrums, but I was interested in the metaphysical workings. The grinding cogs that made it move. We’ll return to this later in this twisted commentary…

I could have probably written something wiser about this, at the time, but I forgot. The point is, at that third episode I thought that maybe Lindelof came up with something good, after all. Some good answers to tricky metaphysical problems. The potential was tangible, because of that one scene.

…Sadly this wasn’t the case.

I’ve only seen the show once, haven’t dug anything from the internet as I use to do, and when I watched it wasn’t even in the best of environments for undivided attention. This to say I might as well miss the big picture. It also applies to the comics, that I read many years ago. After a recent re-read I do think it’s impressive quality, and very, very complex, with many layers that can go entirely ignored (and it’s also a rather heavy read, not particularly enjoyable as a form of entertainment). I certainly missed a lot in it, and these days my mind goes for its own sidetracks that I only can see, but I lose track of main avenues. One that I found recently through another tangent is that Rorschach was conceived as a satire of objectivism, this also being conformed by Moore in interviews. I couldn’t even make the connection after I read it because it doesn’t make any sense, but now I understand better the angle. I did see the right-leaning extremism and absurdity. This is not the place for me to explain how I see Rorschach (not positively, for sure, but not uniquely bad either), I just wanted to point out I missed something BIG, like this link to objectivism, I’m guilty, and I might miss other stuff too.

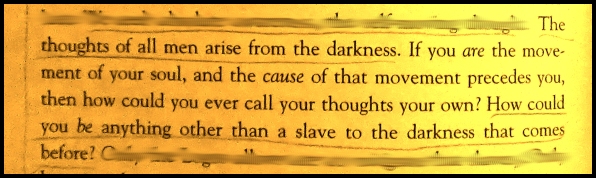

Watchmen defies a simple treatment, it soars above. And so it can be read at different levels. Even if you pick little from it, it’s still quite significant and satisfying. There’s just one aspect that doesn’t work well, and that is also inelegant, and that’s what I wanted to write about because it’s a recurring theme here, linked to previous things I wrote about Ted Chiang and Arrival. It’s related to Alan Moore’s metaphysical (or physical) position that I think he calls Eternalism, and that imagines reality as a solid where time is experienced linearly by humans, but that is all already fixed, like strong determinism. This concept is also what links his recent monster of a book that is Jerusalem, to Watchmen.

Now… The TV show is so devout to the source material that everything it does is already in the comics, including mistakes. This means that what I see as “wrong” in the TV show was already present in the comics. And unless I’m missing some elephant in the room, it’s also conspicuously wrong. Not a tiny detail you can gloss over. I haven’t checked, but I cannot be the only one writing about it, it’s gigantly macroscopic.

I’ve written before that I don’t have any problem with the proposition of eternalism, as long some rules are followed. Moore doesn’t follow them, though. One important rule is that you can, in theory, observe time as a solid, and so perceive it in one immediate instant as Dr. Manhattan supposedly does… but only if this observer remains PASSIVE. Dr. Manhattan in the comics is NOT passive in multiple occasions, including scenes where he describes to others facts that are going to happen in the future (often just dialogues about to happen… to the dumbest character in the comics, this is quite convenient as I’ll show later). This interference creates logical holes and makes the narrative frame fall apart. Moore somewhat goes around this problem, at least at the crucial point. At the climax of the story Dr. Manhattan is confused and his ability to perceive the future is unreliable, because the teleportation of the squid monster to New York created some sort of interference (the tachyons that intrigued also Philip Dick, see one of the “recent” posts).

This idea was readily adopted in the TV show too. The reason why Dr. Manhattan can live a normal life, at least for that segment, is that he was able to create a “blind spot.” A portion of time unknown to him, unseen. Yet, as the TV show explained, he was still able to fully perceive what came before and after. He knew that story would end in tragedy, and he says as much at the beginning (to Angela, he even tells her how long it will last, the blind spot).

All this was well done because nothing in the TV show was “baseless,” all the most weird ideas were simply taken from the comics and used faithfully in a very creative way. Competent sleight of hand. Good.

The problem is that along with the cleverness they also inherited the stupidity… and then made it WORSE. That one spot where it all falls apart. Unraveling with just one tug.

Let’s move closer to this critical point. In the TV series when Dr. Manhattan meets Angela he repeats one of the tricks he showed often in the comics: he tells her that she’s the one who is going to tell him, in the future, information he shouldn’t know yet. And then she does, somewhat proving that his powers are real, after all. This is… fine. The trick is delivered through distraction, essentially. The claim is made, then the conversation goes on a while, and by the time the crucial point is reached Angela has forgotten the initial point. Nothing that happens here contradicts the thesis, the thesis being that Dr. Manhattan sees what will happen, and so none of the participants gets to “act freely”, especially in relation to the ultimate vision. When you deal with something like this it is quite convenient to write the scene so it doesn’t contradict your thesis. The problem is: a thesis is valid when it works logically, not when you sidesteps the contradictions conveniently. It means that I can easily propose, instead, a number of logical experiments that would PROVE, unambiguously, that Dr. Manhattan’s power just cannot work the way it works. These experiments are valid because there’s no logical way around them. The only way is AVOIDING them, writing scenes that do not engage with scenarios that present contradictions. But again, it’s just a convenient trick to avoid facing the fact that the thesis just doesn’t work and isn’t coherent with the premises it itself set.

In a controlled scenario, with no convenient distraction, Angela could easily contradict Dr. Manhattan’s predictions.

Yet, this isn’t totally airtight: you could still assume that Dr. Manhattan uses sleight of hand to introduce his predictions only in those limited cases where the information on the prediction doesn’t end up screwing the prediction. So, he can only tell Angela when he knows Angela will be tricked into the same behavior, and will avoid other cases where a contradiction would be triggered. This way around is still imperfect, to a very close examination, but it’s fine. Within the context of a TV series it is an acceptable compromise.

The problem is that Dr. Manhattan is conspicuously NOT PASSIVE. In the comics there’s the fact he’s confused and, in the end, he cannot do anything to prevent the main event, but in the TV series Dr. Manhattan is the main vector, not a passive observer. He’s the one who sends Veidt, Laurie and Wade away, to perform what they will perform. He is active in the timeline, acting on the basis of what he knows, manipulating events.

The real contradiction isn’t this one, but another that is quite macroscopic. On twitter, before the last episode aired, I asked Jeff Jensen: “I wonder, does Watchmen blindly embrace time paradoxes and contradictions within, as tropes and homages, or will it have something to say of its own?” He didn’t reply.

I was honestly curious because I still thought maybe they had figured out something to find an answer to this problematic core. It turned out they didn’t, and even the final scene was only a retread of The Leftovers: just tickle the audience with an ambiguous finale, open to interpretation. I’ve already seen that. On twitter I commented: “Watchmen ends the same as The Leftovers. With Lindelof still looking for answers.”

In this case “the question” isn’t whether Angela got the powers or not, that’s misdirection. The question is about the contradiction. The giant, gaping logical hole at the CORE of the whole TV series. Again, this hole was already in the comics, but in THAT case it wasn’t the pivotal point, it wasn’t the main vector. Morally, in the comics Dr. Manhattan might be worse even than Rorschach, and he does kill him. All his aloofness is a fraud and Moore certainly painted him very negatively. He’s inhuman and selfish, he gets a treatment (from the writer) that’s very similar to Rorschach himself. No one in the comics is spared, no one comes out in a positive light. They are all creeps and frauds.

This is the one point betrayed in the TV series, that is in love, instead, with at least some of its characters and wants them be GOOD. Especially Dr. Manhattan, who becomes both very human and a benevolent god. The classic trope of self sacrifice done for the loved ones.

And nope, Dr. Manhattan is still a fucking criminal, in the TV series too, despite the misdirection. And here we comes to the contradiction (and maybe me missing some elephantine detail). If I understood it correctly, the main mcguffin of the whole story is that the sheriff is killed. Why is he killed? (whodunnit and why?) Because Angela in the future sends information to the past, through Dr. Manhattan that has this power, to her grandfather. The grandfather who misunderstands the information, wrongly deduces the sheriff is a criminal, and eventually gets to kill him.

Where’s the responsibility? Well, clearly Angela’s not to blame. She was unaware of the implications and only realizes them when it’s too late. She has no power on the whole situation, no choice. But there’s still DOCTOR FUCKING MANHATTAN present on the scene. The same Dr. Manhattan who doesn’t give one fuck if one innocent is murdered for a misunderstanding (or is it guilt for sins of the fathers?). The same Dr. Manhattan who instead intervenes when it comes to save his loved ones.

The Dr. Manhattan who steps in and out the story as he sees fit, while blaming others for HIS actions. And even ending morally celebrated because he saved the day (and loved ones).

The same Dr. Manhattan who loves women and drops them like sacks of potatoes when he’s done with them, replacing them with younger, more attractive ones. Two in the comics, one in the TV series. The same Dr. Manhattan who should be above the instincts of men, and hormones. But what’s clearly a CONDEMNATION of a shitty god *in the comics*, becomes a fucking celebration of a benevolent god who loves his family in the TV series.

What a great way to fuck it all up, Mr. Lindelof.

We still haven’t got to the contradiction. When Angela tells his grandfather about the crime he himself will execute in the future, she makes it happen. Creating the worst kind of time loop. But fine, causality in a time loop gets warped, the problem is that in this specific instance it’s not just causality that goes to shit, but LOGIC TOO. Yes, Lindelof has done this in LOST too, a bad idea stays just as bad. When reiterated it just shows malice.

The is no logical way to explain this scene. It’s just outside logic. And there’s no a-logic metaphysical possibility. Moore’s eternalism isn’t made on illogical premises. It still wants to be a coherent system.

Paradoxes DO NOT EXIST. What we consider paradoxes, or contradictions, are the visible sign that we fucked the interpretation. That we got something wrong in OUR description. The contradiction is never foundational for reasons that should be obvious to anyone who cares to study philosophy (when not immediately evident).

There needs to be a source for Angela’s information. It doesn’t matter where and when, or if time goes around, but it still needs a logical trigger in order to exist. There’s nothing remotely similar to a source shown in the TV series. There’s no single explanation that can verify what happens.

I was really curious before the last episode because it was so blatant. I was expecting they had an ace up their sleeve and found some clever trick to make it work. There was nothing. Lindelof was just content enough by employing a typical sci-fi bootstrap paradox without understanding how it works (there are bootstrap paradoxes that are logical, the origin being just hidden away). Like a nice homage. He couldn’t be arsed to make sense of it, or use it intelligently. Nope, he had to make the paradox itself the pivot and main vector of the whole series, right from the first episode.

He uses as pivot the most stupid of paradoxes, no question asked (hello, The Leftovers, we see the same superficial mistakes again!), and then even ends up rehabilitating Dr. Manhattan as a good guy. The one who’s truly responsible of it all.

Because in the end there is one solution to this paradox, even if it’s the one NOT intended by Lindelof (and very clearly). Dr. Manhattan is not swimming in the aquarium, he’s not “one of us”, living the same life as everyone else. He’s the fucking writer. He sits right next to Lindelof arguing what should happen next. He WILLS the plot, because he writes it, the way he wants. That’s why he’s able to step in and out. That’s why he can carefully shape scenes so that they cannot contradict the thesis. That’s why he can make Angela give his grandfather information that doesn’t exist, anywhere: because it’s Dr. Manhattan who planted that information, who wrote the scene, who made a paradox a paradox. He wrote the dialogues. He makes sure that everyone follows the script because he wrote the script and he wrote those characters. He admired Veidt and plays with dolls. And he ends up writing the story where he ends up as a hero. Because he’s full of shit.

Moore made his own mistakes with Dr. Manhattan and eternalism. But they were minor and he didn’t fuck up the overall concept at the core: that all these heroes were all fucked up, Dr. Manhattan more than everyone else. Lindelof studies and mimics everything so carefully that it’s all a labor of pure love… Only to fuck it all up.

How it is possible that a show so well put together, down to the smallest detail, doesn’t have a problem founding itself on a blatant, enormous contradiction? I don’t understand.

—

Edit:

and… only after writing this whole thing I realized that Dr. Manhattan, might be completely in the dark, literally, about the whole deal with the sheriff, because that whole event could be encapsulated within the blind spot of his life as a human. So he might be entirely unaware of all that happened to the sheriff, so that he didn’t know that an innocent would die. Angela understands, but then doesn’t inform Dr. Manhattan of anything. I’d have to rewatch the scene to see if the part in the future makes sense. Still… there’s the bootstrap paradox.