Curiously enough, my reaction to this book reflects the palindromic structure that defines a powerful form of poetry called “ketek” used in the book: I did not like at all the first and last 50 pages, but thankfully enjoyed enough everything in between (that for a book of 1000 pages is quite enough). I wrote already about some of my concerns about the writing in the Prelude/Prologue, while what I didn’t like about the last 50 pages was more structural. 150 pages from the end of the book I already know the ending was going to disappoint me, in fact it did, for the reasons I had envisioned, but that last chunk was worse because it makes me reconsider critically the whole thing.

Curiously enough, my reaction to this book reflects the palindromic structure that defines a powerful form of poetry called “ketek” used in the book: I did not like at all the first and last 50 pages, but thankfully enjoyed enough everything in between (that for a book of 1000 pages is quite enough). I wrote already about some of my concerns about the writing in the Prelude/Prologue, while what I didn’t like about the last 50 pages was more structural. 150 pages from the end of the book I already know the ending was going to disappoint me, in fact it did, for the reasons I had envisioned, but that last chunk was worse because it makes me reconsider critically the whole thing.

Without spoilers, I can say the Epilogue questions the true value of art. It reads somewhat like a “meta” discussion on the genre, and implicitly Sanderson’s role as a writer of Fantasy:

“In this,” Wit said, “as in all things, our actions give us away. If an artist creates a work of powerful beauty – using new and innovative techniques – she will be lauded as a master, and will launch a new movement in aesthetics. Yet what if another, working independently with that exact level of skill, were to make the same accomplishments the very next month? Would she find similar acclaim? No. She’d be called derivative.

“So it’s not beauty itself we admire. It’s not the force of intellect. It’s not the invention, aesthetics, or capacity itself. The greatest talent we think a man can have?” He plucked a final string. “Seems to me that it must be nothing more than novelty.”

So it’s “novelty” to be the heart of art, but that’s only the partial answer, because then the Epilogue goes further to suggest the ultimate one:

“What is it we value?” Wit whispered. “Innovation. Originality. Novelty. But most importantly… timeliness.”

Now… Am I too naughty if I just can’t avoid thinking this last line as a prank on Sanderson’s own doings? If “The Way of Kings” can’t be innovative, original or novel, then maybe it can still be used fruitfully if it’s at least “timely”. And what’s more “timely” than launching your own 10-books series right amidst the release of the very end of the Wheel of Time, when the interest in said writer is at the highest peak? The Way of Kings is indeed quite timely. Well, I don’t understand what Sanderson wanted to do with this Epilogue, but I doubt very much he wanted it to be interpreted like this.

A step back. This is the first book of a 10 book series and Sanderson’s most ambitious effort. And not only since he already hinted at an even much bigger structure (especially “Hoid”, a mysterious character that transcends what happens in this book) of which this whole series is only a part. This doesn’t discourage me at all since I enjoy insane ambition and I also, contrary to most readers, prefer to read books in a series spread out instead of in quick succession. So I start here and expect to follow along whenever Sanderson will finish the next book (it will be a while and the wait will likely renovate my interest). But it should be said that, as it is now the habit, the book does a nice job offering a storyline that is concluded in a satisfying way within the book, while hinting more about what is to come. It means that one shouldn’t be discouraged by the fact it’s only one book, with the following one not coming out for a couple of years.

Can’t say anything how this book stands compared to those the author already published since this is the first thing I read of him. The writing style of the Prologue was for me so awful that I wondered if I could go on, but then those issues vanished from the first chapter onward. Partly because I was drawn more into the story and characters, easing to the writing style and so not using up all my attention nitpicking, but also because those aspects I dislike were more diluted and less prevalent. There’s something in the style of writing that works at the same time as a strength and weakness. I’d define it as overall “didactic”. Not a bad word, but it could be seen as problematic in this context. Sanderson is very good at explaining stuff, teaching somehow. For a first book in a series this is a strength because there’s a lot of attention in giving the setting a distinctive sense of place. The nature of the world demands that details like plants and atmospheric interaction with these plants are strictly involved with what is going on in the story, so the book carries the reader along in a learning experience about this world, letting all (important, not simply incidental) details being slowly absorbed. There’s some redundancy involved, that at times feels excessive and giving the idea that the writer doesn’t trust enough the receptiveness of the reader, but there’s more to it that can’t be dismissed. The book, on a higher level, is “curious”, and stimulates curiosity in the readers. This is why exposition or “infodumps” that take a significant part of the book aren’t detrimental or heavy. The recipe, I think, is the most successful part of the book. You have a very manageable number of characters, well defined, easily understood, and you borrow some of their positive traits, including the curiosity for the world. Constructive, well measured. An aspect I noticed that is linked to this overall “didactic” writing style is an excess of question marks. There are questions crowding every single page. Many questions. The question is the most significant foundation the characterization relies on here. The effect is that the main characters that drive the book are very transparent to the reader. Every thought is introduced by questions, explained, rehashed. Open books. Characters whose totality is easily grasped, so easing the identification and understanding of actions. Even in those few cases where characters have some secrets (Kaladin’s past and flashbacks through the book) you are only forbid the premises, but you still see clearly the consequences and left wondering what caused them. It tickles the curiosity without making characters act unpredictably. You know exactly who’s doing what and why, and this usually leads to a decent characterization.

Everything I said leads to another problem, though. The micro and macro levels, about which I’m more critical. What I mean is that the book works on two levels, as an overall structure. In general all long epics rely on a similar structure. The “micro” level is the single character PoV, his own plans and actions, his range of troubles and expectations. The “macro” level is the higher level of the plot, the overarching structure of greater import that links all characters and make them face much bigger scenarios. The fate of a world VS the fate of a character. It’s like a shifting level of detail: you can zoom in closely on a character, get carried on with his daily life, slice of life. Character’s stories on a personal level. A fantasy world is like a huge container of millions of lives and millions of stories, so you can ideally always zoom in and find something personal that is worth narrating and that will catch the attention. Kaladin and Shallan are the two main characters in this book that carry the most this “micro” level. The interest is focused on the immediate troubles and their potential solutions. The various chapters are neatly organized to drive the reader on, ending up teasing for more. Then there’s a macro level that defines where these and more characters stand in the greater scheme of things. The book does not hide one level from the other and makes the macro level very visible right from the start. You always have the idea there’s more at stake than what is immediately close, the larger horizon. But this is where for me the book didn’t quite reach. What I anticipated through the book didn’t happen within the book and I’m not even sure of how late it will come in the series. There’s a very long and large build-up, both macro and micro. The micro works (with reservations I’ll explain), but the macro is entirely undelivered.

In the end, having read the whole book, the structure feels too much like ASoIaF: imminent danger coming from a side of the world (east, this time), but the kingdom is divided and not prepared. And, as in ASoIaF, this is the situation at the beginning of the book, and it is the exact same situation by the time the book ends. Nothing moved on the “macro” in a sensible and significant way. Even worse, the end of the book gives a strong idea of sweeping changes that to me look like blatant illusions thrown at the reader. I fear that book 2 will show how nothing at all changed and we’ll be plunged for another 1000 pages in minor character squabbles, only to arrive to the last 50 pages and have again sudden hints of major plot twists that in the end consolidate to almost nothing. Too much set-up and too much economizing on this level. It feels very drawn out.

On the micro it works much better. There’s plenty of payoff, lots of plot twists and unexpected surprises, all cleverly handled and satisfying. It works on these details, but I have some reservations. The first is that with a slow moving, carefully detailed plot, you can see where things are heading sometimes HUNDREDS of pages before they happen. While this micro level is fun to read, this kind of predictable horizon can cast on it a negative shadow. You know where things are headed, even if you don’t know the specifics of how it will be done. These specifics are well built and receive a significant care from Sanderson, but if you know where they are going then you also have a jaded and tired reaction, and it detracts from building momentum and make for a fast, satisfying read (what other readers call “the book could lose another 200 pages”). The other reservation is the odd structure. With three or so major viewpoints one expect the chapters to alternate regularly, but not here. Kaladin is basically the only one constant through the book, alternating with whoever is on stage at that point. Shallan viewpoint is a significant presence for half the book, but then it vanishes in the middle only to reappear in the last 100 pages. Similarly, Dalinar arrives late, then vanishes for 300+ pages before resurfacing again, and it wasn’t something I enjoyed much since it was my favorite to read. Obviously there are good reasons why this uneven structure is used, but it adds to the negative feel of plot moving slowly (not exactly, I explained in this same paragraph what I mean) when you consider that these viewpoints depart for hundreds of pages before they can lead to something.

Another concern I have comes out in the latter part of the book and has to do with the plot being too clearly driven by hand. While Sanderson does a very good work explaining characters’ motivations and actions, so making a reader accept the number of fancy elements of the plot, giving it an idea of coherence and credibility (worldbuilding included), in the latter part things are drawn together in a very blatant and obvious way that makes everything fit in place for the intended effect. Said intended effect predictable in a number of cases. Too much straight heroic, a bit trite. Also by the end of the book Kaladin still is the recalcitrant hero he was at the beginning, and that side of him was getting particularly annoying. I had expected to see him changed in a more significant way beside the superpowers. And feels too much like another Rand, on this level.

Instead I liked what was going on the political level and liked particularly the conclusion on the micro level here. I felt like this book somewhat “healed” a wound open since “A Game of Thrones”. As if Sanderson wanted to tell that story in his own way. I think it worked well and I enjoyed it. Obviously I can’t tell anything more without spoilers, but, even if this book won’t challenge Martin’s, I still liked Sanderson’s take. The politics and internal struggles are far more simplified than in A Game of Thrones, not actually the focus, but the interplay is well done and well built. Well connected with the worldbuilding related to it.

Not surprising that Sanderson is not between my favorite writers, I didn’t come with that kind of expectations. But I enjoyed the book even if I expected something more significant to happen before it ended, something more bold in exposition (and a number of suspicions I had stay unconfirmed since the book didn’t provide answers for most those questions I thought intriguing). It’s an accessible book that can be easily recommended to readers who enjoy lingering with characters and feel immersed. It has many qualities on its own, but I think it misses something like a major draw for the public that the Wheel of Time has. Sanderson will have to work harder if he actually aims at excellence. For now he has a nice following and in the end I think he deserves it. He’s a good guy, clever enough to be interesting to read, and would make a very good teacher, actually. He’s one of the guys who “care”, or at least it’s the impression I get from reading the book.

P.S.

Couldn’t fit in the flow of the review, but my favorite parts of the book were the interludes, especially Axies who reminded me a bit of Malazan’s Heboric, and chapter 33 “Cymatic” with Shallan, for how it engaged with the macro level and was quite interesting to read.

The pain with this book more than reading it is trying to write a review. How to frame it? It left me reeling for sure. There are a number of ideas explored that seemed to echo with some my own thoughts pre-existing the book, this further reflected toward the end of the book by a strong in and out of text deja-vu whose implications are far too tangled for me to make any sense of them (I should also try to second-guess some that Bakker did, that would bring a whole new level of complication). Just to say: the book messed a bit with my head. But that was almost expected, knowing well the kind of writer. The blending in and out of character, in and out of the book, and between facets of different characters echoing each other is a prevalent defining trait.

The pain with this book more than reading it is trying to write a review. How to frame it? It left me reeling for sure. There are a number of ideas explored that seemed to echo with some my own thoughts pre-existing the book, this further reflected toward the end of the book by a strong in and out of text deja-vu whose implications are far too tangled for me to make any sense of them (I should also try to second-guess some that Bakker did, that would bring a whole new level of complication). Just to say: the book messed a bit with my head. But that was almost expected, knowing well the kind of writer. The blending in and out of character, in and out of the book, and between facets of different characters echoing each other is a prevalent defining trait. Another attempt at polishing the review I’ve written. I usually adjust a few things after I post one but in this case I was less satisfied than usual because I gave too much importance to certain aspects and almost ignored others that I think are more important. The biggest problem was that I wrote my comments just an hour after finishing the book and I started to understand the book better while writing those comments, which caused them to be even more rambling than usual. So I’ll do some cut & paste and restructuring.

Another attempt at polishing the review I’ve written. I usually adjust a few things after I post one but in this case I was less satisfied than usual because I gave too much importance to certain aspects and almost ignored others that I think are more important. The biggest problem was that I wrote my comments just an hour after finishing the book and I started to understand the book better while writing those comments, which caused them to be even more rambling than usual. So I’ll do some cut & paste and restructuring. This is a lean book that took me to read way more than expected, mostly because it fits the “other read” while I was engaged with more meaty books. A debut, as a writer writing books instead of comics, and first in a rather long series made of standalones. This is where Dan Abnett started writing Warhammer 40K, accordingly to the internet not his best effort in the field, but a decent and solid one still. Optional as a starting point since one could start right with Eisenhorn or the multi-writer crossover of the “Horus Heresy” currently being published. Instead this specific series, whose opening volume is “First and Only”, is made of twelve books already released with more planned, but the number shouldn’t discourage as the story moves either through standalone stories or story arcs that are over in three or four books. There are also these nice & cheap omnibus that pack together those arcs in mammoths of 800-1000 pages, so you’re not chasing in frustration a conclusion that never comes. You can satisfyingly read just one and stop, or go on as far as you want, guilt-free.

This is a lean book that took me to read way more than expected, mostly because it fits the “other read” while I was engaged with more meaty books. A debut, as a writer writing books instead of comics, and first in a rather long series made of standalones. This is where Dan Abnett started writing Warhammer 40K, accordingly to the internet not his best effort in the field, but a decent and solid one still. Optional as a starting point since one could start right with Eisenhorn or the multi-writer crossover of the “Horus Heresy” currently being published. Instead this specific series, whose opening volume is “First and Only”, is made of twelve books already released with more planned, but the number shouldn’t discourage as the story moves either through standalone stories or story arcs that are over in three or four books. There are also these nice & cheap omnibus that pack together those arcs in mammoths of 800-1000 pages, so you’re not chasing in frustration a conclusion that never comes. You can satisfyingly read just one and stop, or go on as far as you want, guilt-free. I began to read the book almost a year ago but got sidetracked after about 70 pages, so when I took it again a couple of weeks ago I had to restart from the first page since I had a very vague idea about the part I had read. Not that it got so much better the second time through, the story defies control and one has to struggle to distill from the book some form of logic progression. Reading this, day after day, feels like you never make any progress, which I guess is the point. There’s a direction, a sort of abstraction of the concept of the “quest” in its most absolute form. The endless, ultimate journey toward something that is perceived as the definitive “Truth”. Or better, this is the conceit, the Mac Guffin. Roland, the Gunslinger, on his journey toward a mythical, capitalized Dark Tower. Only that this is one book, part of a series. So for this single instance Roland is chasing after another Mac Guffin, the “man in black”, who, when caught, would hopefully point Roland in the right direction.

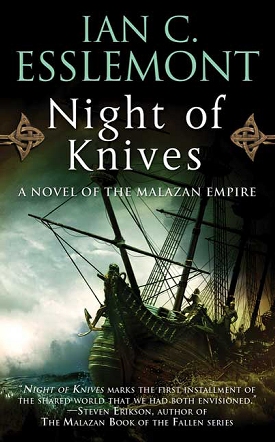

I began to read the book almost a year ago but got sidetracked after about 70 pages, so when I took it again a couple of weeks ago I had to restart from the first page since I had a very vague idea about the part I had read. Not that it got so much better the second time through, the story defies control and one has to struggle to distill from the book some form of logic progression. Reading this, day after day, feels like you never make any progress, which I guess is the point. There’s a direction, a sort of abstraction of the concept of the “quest” in its most absolute form. The endless, ultimate journey toward something that is perceived as the definitive “Truth”. Or better, this is the conceit, the Mac Guffin. Roland, the Gunslinger, on his journey toward a mythical, capitalized Dark Tower. Only that this is one book, part of a series. So for this single instance Roland is chasing after another Mac Guffin, the “man in black”, who, when caught, would hopefully point Roland in the right direction. “Night of Knives” is the first novel(-la) written by Ian Cameron Esslemont set in the Malazan world co-created with Steven Erikson. It’s a much leaner book, 300 pages in the american Tor edition, compared to Malazan standard, and chronologically set between the prologue and first chapter of “Gardens of the Moon”, the first book in the series. Yet, the fans recommend to read the book only before the sixth because of some connections, while I decided to anticipate it right after the fourth, since “House of Chains” deals more directly with the matters of the Malazan empire and I wanted to approach “Night of Knives” when that strand of story was still fresh in my memory.

“Night of Knives” is the first novel(-la) written by Ian Cameron Esslemont set in the Malazan world co-created with Steven Erikson. It’s a much leaner book, 300 pages in the american Tor edition, compared to Malazan standard, and chronologically set between the prologue and first chapter of “Gardens of the Moon”, the first book in the series. Yet, the fans recommend to read the book only before the sixth because of some connections, while I decided to anticipate it right after the fourth, since “House of Chains” deals more directly with the matters of the Malazan empire and I wanted to approach “Night of Knives” when that strand of story was still fresh in my memory.