“There is no magic. There is only knowledge, more or less hidden.”

(…)

“That is the wisest of all the books of men,” the Cumaean said. “Though there are few who can gain any benefit from reading it.”

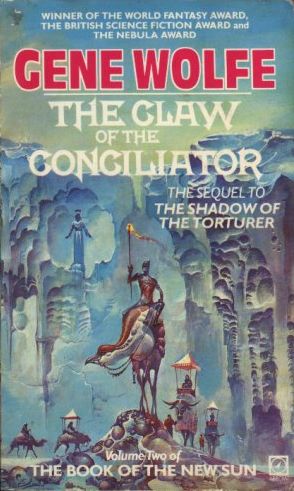

The Claw of the Conciliator is the second book in the New Sun tetralogy. Or second of twelve if one considers the “Solar Cycle” as a whole. Since it takes me so long to finish a book, and since I don’t write about all books I read, I prefer to stick to the smaller unit available and comment as I move through. But, since I keep getting interested in other writers and series, it happens that quite some time passes before I return to something I begun (and these loops keep getting larger). So, looking at my blog, it’s been more than three years since I read the first part, The Shadow of the Torturer.

Most of what I have to say about this book is part of a general thought about Gene Wolfe. More than once in forum discussions I have defined him “esoteric”, in the original definition of the term. I tend to lump all writers in two groups: esoteric and generous. The difference is about the “intent” of the writer. Esoteric writers write books that are only accessible for a selected minority of like-minded, or sharing a certain status or cultural education, whereas generous writers are those that desperately try to make “communication” happen, whatever it takes. Generous books could retain all the complexity and ambition while taking time to teach the reader how to approach and extricate the work they are reading. They usually reward patience, but ultimately they reward it by letting you reach in and grasp their core. It’s not a matter of complexity, but of offering ways to access it. Esoteric works instead are “hidden knowledge”, they have high walls surrounding themselves and only those who have the password or know the secret sign are let through. Otherwise you’re left outside desperately trying to see through the wall and sometime feeling like you’re seeing some vague shape of what’s beyond. But you’re wrong.

Wolfe embodies this esoterism to its full symbolic value, to the point that what I described here with a rather negative connotation, becomes a positive one. This because, like the best works, the reader (and his re-action) is part of it. One thing that this work is doing is putting the reader out of balance and warp the space around him. It’s a dislocating effect, but not of the kind that prepares entering another world. Here the dislocation is the point, the message. Time, especially, collapses on itself, as if at the end of the world, before the New Sun arises, everything appears simultaneously.

This is relevant, specifically, to this book I was reading. It’s a kind of book that I loved and at the same time I wanted to hurl at the wall. Frustrating at the point of rage, but also possessing some brilliance that is right out of the corner of your eye, but that you absolutely know is not the kind that /just/ deceives. Imagine a calm sea in the night, the New Sun series is wholly contained below the surface. You see nothing. That’s my reaction starting to read it again from the first pages. On the surface there are characters, things happen, then you finish a chapter, begin another and there’s a new episode that seems to be only vaguely related to the one you just read. One uses to review books through certain patterns, so we examine characters, plot, pacing. But doing the same with the New Sun would end up in disaster. From my point of view and direct reaction while reading, this book has no sense of “plot”, or cause and effect. If one complains about arbitrary interventions (deus ex machina) here he could find them more than once within a single chapter, almost the sole force driving the plot. Characters do things seemingly without motivations, say things that make no sense, hypnotically dazed as in a movie by Werner Herzog. The scenes change from chapter to chapter as if part of unrelated episodes. This would really be a disaster, if it wasn’t that the problem is not in the material, but in the categories used on it.

Similarly, Severian is not the prime example of a character you can sympathize/empathize with. Quite the contrary. In fact I was thinking he may be the most horrifying character I’ve ever encountered. Early in the book there’s an episode where he has to perform a public execution. The horrifying part is not the execution per se and its gruesome description (“To be candid, it was not until I saw the up-jetting fountain of blood and heard the thud of the head striking the platform that I knew I had carried it off.“), but the reaction Severian has (“I wanted to laugh and caper.“). He GLOATS and parades grotesquely on the scaffold, showing proudly the severed head as he feels so happy that he was able to perform a tricky move with his sword. He continues to gloat even when it is revealed that the woman he just executed was innocent, victim of a machination. This gave me a profound feeling of amorality, of cold, alien detachment. Something entirely inhuman. It is horrifying but it also adheres to Severian the character, with his pragmatic, weightless mind that feels so alien to me. What is done is done, and very professionally from his perspective, everything else is simply not affecting him. He doesn’t even consider any other perspective. Which brings to a sort of salvation. His mind is so bent inward that he’s neither “good” nor “bad”. He seems unaware and unable to have a real, human existence because he has no experience of anything else. And so he’s also without guilt since he’s utterly naive and unable to make a choice (making him the embodiment of a pawn).

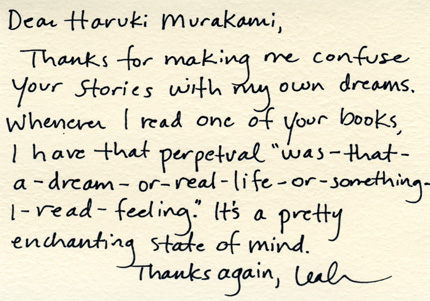

Wolfe demands a different approach from the reader and different ways to carve “meaning” from it. The most important rule is the “dream” (and Neil Gaiman featuring on all covers and introductions isn’t casual). What is narrated in this series has the “dreamlike” quality. That’s why everything you “see” (surface of the water) is “not the point” and apparently doesn’t seem to make sense in a strict, logical way. Every image or character is symbolic, and its symbolic weight has priority on superficial appearance. As in dreams scenes change with a loose sense of connection and everything goes to build this eerie, magical and ephemeral atmosphere (and as in dreams “time” collapses on itself). Words carry not meaning, but fascination and hidden construction. Giving a sense of dizziness and, as said, dislocation. Not toward a different “environment”, but toward a different “fabric” of reality. That in this case is the fabric of the dreams, and the world built through this symbolic projection of hidden and obscure powers and mythological beings. Lovecraft’s monsters made into pure ideas.

The problem, if a “problem” exists, is in the consequences. Reading page by page that’s the way I was feeling. Understanding clearly that there was “more” to what I was reading, that Wolfe was describing factually an episode but “doing” something else, hidden. Neither showing, nor telling. He hinted and teased, keep luring you. Deceiving. The problem of the esoteric work is when you hit the wall, again and again. Feeling that there’s more to it but without ways to get through. So I’m very critical about “how” Wolfe does things, because I feel he WANTS to keep me away, he WANTS to bait me in this malicious game and its hidden, obscure rules. It’s like in the myth of Theseus and the minotaur (a myth he specifically uses in this book), with Theseus going in the labyrinth from where no one returned alive to kill the minotaur. You are Theseus, Wolfe is the minotaur. The problem is that in the myth Theseus is told how to get out of the labyrinth (he’s given a ball of thread), while you, the reader, are left to the Wolfe/minotaur’s mercy.

I am in the presence of a practitioner whose moves I cannot follow; I see only the same illusions that are seen by those outside the guild [of writers]. I know the cards are up the sleeves somewhere, but there are clearly extra arms to this person.

Even in forum discussions one tries to get help figuring out this and that, but in most if not all cases it seems like one only gets evasive explanations that stack together in some kind of misshapen structure, but that do not seem anchored anywhere. It’s always a game of smoke and mirrors (mirrors that play a symbolic part in the books). And it’s frustrating because at some point you begin squinting so much that you get the illusion of seeing something, with the omnipresent doubt that you’re only imagining it. Being so ephemeral and deliberately obfuscated, it encourages speculation, but one has to know that it only goes to feed the minotaur.

This is my opinion of the book. If I decided to read the whole cycle of 12 books (eventually) is not because I expected a fun, enjoyable adventure. It is instead because I’m interested in that “underworld” of meaning, hidden just below the surface. My problem with it is that Wolfe builds walls that I can’t get through no matter how hard I could try, and this leads to a frustrating experience. He isn’t interested to let me in as much as in throwing puzzles and riddles at me to solve, without giving me nearly enough pieces so that the solution is even possible. The whole paradigm is a paradox. It carries over to the prose style as he uses often a pattern of inversion. Things that are or behave inversely than how they appear. You are left solving a malicious, impossible puzzle that reassembles itself whenever you get close to something. And this would be indeed a “problem” if it wasn’t also part of the point.

The Book of the New Sun is too complex a work to evaluate on one reading. It will undoubtedly be considered a landmark in the field, one that perhaps marks the turning point of science fiction from content to style, from matter to manner.

I wonder if going from “content” to “style” is a worthwhile mission. Wolfe indeed has a dense, ornate and convoluted, I’d say elegant prose style that is often dull and hard to follow. It’s also not banal, so it keeps the attention on what he’s doing and how. It requires certainly a constant attention, similar to some eastern non commercial movies, where the pivotal moment can be one where no characters speak, not highlighted in dramatic music at max volume. You let go your attention in a moment that appeared as a mere transition nested between two more important scenes, and you miss everything.

The “underworld” is certainly intriguing. It’s a big tangle of erudition, Wolfe taking all sort of mythic, religious and scientific notions from all known cultures, then removing their context and merging and transforming them till they become unrecognizable. A “decontextualized apocrypha”. But doing this he also realizes the transformation of culture through the ages, how the original meaning is lost forever, prompting something new. Many of these ideas touch cosmological arguments that I’ve hinted here and there on the blog (before I started to read this, it’s just stuff that intrigues me). There’s more than one reference to the Kabbalah and it’s interesting to track what Wolfe is doing with it since it’s what gives the larger framework. But he also leaves me with the impression that it’s all an elaborate labyrinth of misdirection. With mostly dead ends. For example when I read Erikson I can see the themes surfacing, reflecting on different perspectives, returning from different angles. But Wolfe is so busy hiding all meaning that he can’t also offer a discourse. He leaves things uncommented, simply stated or hinted, but never faced or directly experienced.

The gulf between plot and story, between the apparent and the real, alerts the reader to the fact that Wolfe is playing a complex and contrived textual game.

It’s a floating cathedral of meaning. It’s built on a artifice, risking of remaining detached and, so, irrelevant. But it’s from there that it also draws its undeniable qualities. The reader is a deliberate part of this game. The “purpose” of the series is not directly in the hidden message that keeps frustrating and irritating me, but in its effect on the reader. It’s strictly in the bleeding to death in front of the minotaur:

Rather, by effectively concealing his narratological sleight of hand and constructing a puzzle for his reader, Wolfe attempts to alert that reader to the level of perception required. Hence, The Book of the New Sun does not invite the reader to marvel at how clever Wolfe can be, but to marvel at his or her own intelligence in perceiving one facet of the elaborate textual game the author plays. In this sense, Wolfe’s tetralogy is a masterwork in that it can be read as a paraliterary fantasy but demands to be read as a comment upon, and a reaction to, such narratives. In effect, it is a coolly intellectual denunciation of passive reading practices, a clarion call to readers dulled by formula fiction.

It is only by observing how s/he has been deceived and cajoled that the reader comes to appreciate more fully Wolfe’s vision of humanity as a helplessly subjective species attendant to the whim of manipulatory forces. This observation is encouraged by the self-conscious stress on deception, artifice and artificiality that permeates the text and which emblematises Wolfe’s textual game with the reader.

From his other fiction, it apparent that Wolfe perceives the world as an ambiguous round of perceptions and misperceptions in which the individual struggles, and ultimately fails, to apprehend the precise nature of existence.

You try to understand, and the moment you feel like you can do it, taking up the challenge, is the moment you give the minotaur the vantage point to slay you.

What I continue to criticize, in opposition to that quote, is the fact that this game IS indeed indulgent, self-focused and self-serving. Sophistication bordering on narcissism. It is not a case that those who are passionate the most about this series are those that ascribe to it “literary” value, putting it one step above all other works of fantasy and Sci-fi (and so reiterating the same pattern). This “pretense” is for me very visible in the books and its style, not just its readers. And in the way it actively selects its readers, while rising barricades to those not “erudite” enough. The cold disregard. It’s not as much as being “sincere” and faithful to itself (“I thought them [the complex jargon] the best ones for the story I was trying to tell.”), as it is a deliberate will to create its elitist, esoteric group of like-minded who can properly perceive the subtext and savor the complex fabric. It’s the practice of literary snobbery and sophistication, secluded and removed. It doesn’t work by making the reader “feel” that complex experience, but actually failing at triggering ANY emotion, as long one is rejected and can only glide hopelessly on the surface. More often than not that’s the reader’s experience, and it will only be enjoyed by that selected elite that can ridicule that reader that tried to get in and failed miserably. Wolfe transforms the patient reader in one that can and should be taunted and laughed at.

So while there’s certainly a great value in this work. It is surely also very pretentious and written to gratify a certain public. A narrow public carefully selected to appreciate the sophistication, and that Wolfe had precisely on his mind when he wrote these books.

(if you’re interested, there’s a lengthy forum discussion that precedes this I’ve written here)

(and this is instead the insightful review that I quoted in mine)