Four brothers go to the beach

Here comes a youthful and cute blonde girl. She’s very excited to come to the ocean on holiday. Her hair up in a ponytail, she’s put on her armrests and pulled up the lifebuoy around her waist, already hopping toward the water. As the level rises, she starts to float, flapping her arms and realizing that with all that bulk around her she’s not going to move freely very much. But it feels safe and the water is nice, with some effort she manages to turn around to face the beach once again and cheer her beloved brothers. Her name is Brenda.

Next comes Stevie. A wiry, happy kid wearing some ragged, mismatched clothes. He does look a bit malnourished but at the same time seems quite energetic. He doesn’t wait a second, he pushes down his pants and pulls out his shirt, to remain completely naked. Then he runs stampeding straight into the water! He’s never seen the ocean before, he never learned how to swim either. Just a moment and only bubbles are left. Oh well, he’s already drowned. But no! There he is, resurfacing not far away, sputtering, coughing, going under again. Brenda is watching, looking a bit perplexed, if not concerned. But Stevie keeps coming back up, eventually. He seems to be spending more time under the water than above, probably not by choice. Maybe he enjoys more diving than swimming, but you assume he’s having fun. Now Brenda is splashing some water in his direction, which probably doesn’t help, but doesn’t seem to hurt either.

All the while, impassible as marble stature, stands and watches George, the oldest brother. Eyes shielded by expensive-looking sunglasses, lean and handsome like no other. Projecting a sense of confidence and safety, completely in control of his own circumstances. He’s there watching silently until something must have signaled him everything’s alright. As he gets to the water he doesn’t spare a glance to his brothers anymore. He swims onward, a perfect freestyle as if practiced in an Olympic pool. The water parts to his mighty arm strokes. A marvel to see, a master of his technique. He has no fun. He performs.

But what happened to the fourth brother? He’s always been the quirky one, who went invisible most of the time until too late, when you realize he provoked some complete disaster. George didn’t even have time to turn and see. Richard is running on the water like a fucking Jesus Christ. He said he doesn’t care about swimming. He’s already just one small dot, at the horizon. He said he decided to cross the ocean. Brenda doesn’t even know he exists.

I wrote this when I started reading the book, but decided back then that this was going to be the beginning. So it is.

—

(probably this whole thing still needs a better clean up… Sorry.)

and the Sons of Men threw back their heads, their mouths pits in their beards, their looks shining and hopeless, eyes that mirrored the flailing that is the final recourse of all blooded things.

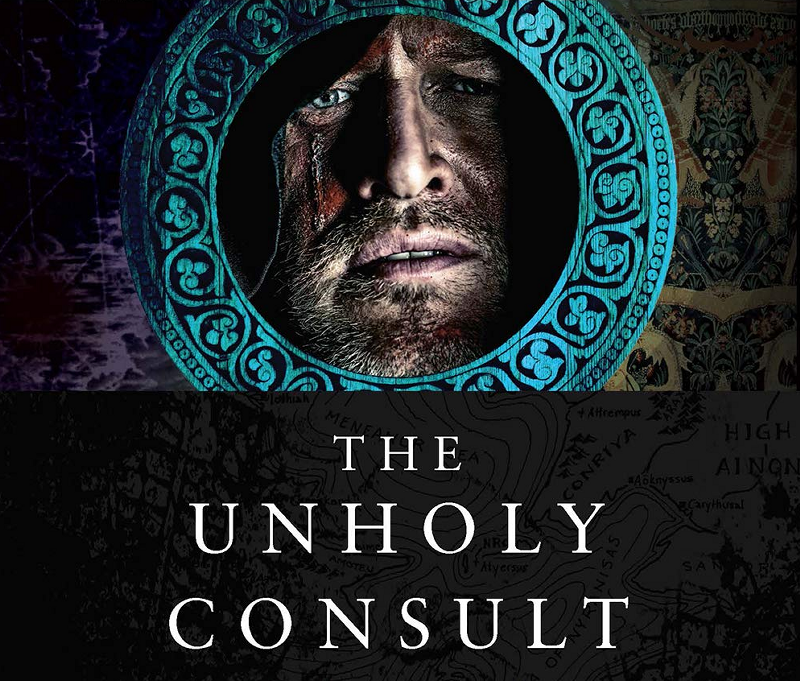

I did not enjoy reading this book. The reason is more personal than lending itself to a review of the book and the experience was similar to reading the third, the finale of the first trilogy. With the obvious exception that there is no… resumption waiting afterwards, this time. There is nothing else. A literal apocalypse for the series. There are no other scraps of paper to read with the promise of resolution. I finished reading the book, went to bed, and couldn’t sleep for several hours. I felt like haunted. Now I’m trying to write this already exhausted.

At the halfway point of the book some things were being resolved, but less like resolved than brutally chopped off and left bleeding on the ground (Sorweel). That point was where I started to think. That there wasn’t enough of a book left. There was no space. For anything. I was suspended into a contrast, because I still held onto something, despite the book pushing in another direction… When I started to read the first page of the summary, at the very beginning, I immediately jumped to the appendix. Because like with the third book there’s an expansive glossary. And so, right while reading the very first page, I decided to go check what the glossary had to say about the “Apocalypse.” To find that there’s a long entry, precisely copied as it was from book 3. But. It started with two new words. The whole three pages or so long entry was all identical, save those two words at the beginning. System initiation. Nothing else. This hook held me through the reading of the whole book: there had to be some meaning.

There had to be some meaning, and I was 200 pages from the end. Then I was 150 pages away. Then 100. Not only there wasn’t enough space for anything I cared about, but there wasn’t enough space even for the surface of the plot. And then 20 pages. TEN. And then there was nothing left.

On a personal level, I’d have liked the book better if there was no battle and just more people talking. But this is what Bakker wanted. He wanted a battle, he wanted it to be big and take his time creating a staggering sense of wonder. He wanted scripture, of a present already encoded as a mythical age. He would create the awe and continue to elevate the proportions. Once again challenging Tolkien and surpassing, at all levels. The writing, the spectacle, the profundity, Pure plot matching theme, written into it. It is a deliberate book and, I guess, a deliberate disappointment as well.

I did not enjoy reading because at that halfway point I realized that I could not expect anything anymore. I realized what the rest of the book was going to be about. And so reading became an exercise in frustration and an anxiety of feeling a rush in the wrong direction. I realized, as I already expected, that it was a book that wouldn’t look forward, but backwards. Without adding anything. Without breaching the perimeter already drawn, but being pinched and squeezed. As if the book itself became a trap for the occlusion. A space that could not be escaped. A limit that progressively closed and choked. Until no page was left. Until nothing else could be said.

The book dissolved into plot and theme, as strong or stronger they ever were. It became a voice of the apocalypse. There’s a point where the gravity center imposed a pull, and everything was dragged in. Through this, the book delivered all that it wanted to be. A maelstrom that punctuates the finale to the first part that was The Great Ordeal. But, as the deafening scream of the whirlpool, it took the voice away from everything else. It annihilated everything I wanted to know and read about, to deliver misery heightened, but still re-enacted as it was in ALL the previous books, including the first. Now especially, that I closed the page of the last book, I can say everything starts and ends with the first book. That nothing beyond that was more.

I’m too tired and conflicted to hope of giving all this a neat and organized shape. So it’s now all spoilers domain and unsubtle discussion about practicalities. As I said, almost nothing in the book spoke “to me”, or the layer of philosophy and meaning I care about. I guess I’ll write later about this but some expectations about the “semantic apocalypse” went out of the window right from the start. So the book is not what *I* want. That’s fine. It’s absurdly well written and in no way a decline from the previous, exceptional book. But beside all this, and my conflicted view, I have some plain issues about the nature of the plot, to then move to the implications and everything else…

The ending of it all was something that, I think, I could have guessed without much effort, if I closed the book and started to think. Not the reveal about the Dunyain taking over the Ark, that part blindsided me and couldn’t be guessed. But the intervention of Kelmomas was exactly as it would have been. It worked following the same patterns that came before, in the way Bakker forgets about the kid for so many pages, making it another Chekhov gun, as immense as the Ark. Maithanet was killed by a blind spot. The White-Luck warrior, through the intervention of Kelmomas, was killed by a blind spot. Sorweel was killed by a blind spot (again Kelmomas), leaving all the other gods like pathetic wolves who lost all teeth. The most likely outcome on the table was that Kellhus was going to also be fooled, at the end. And he was. Certainty is always humiliated in these books. No one is master. Only unknown unknowns.

The problem is how. So many times we’ve been told how Dunyain brain parallelizes processes like a multi-threading CPU. How they “partition” their mind so that different parts take care of different aspects. And yet here Kellhus isn’t simply surprised by the apparition of his son, unplanned and unseen. But his demise is due to a LOSS of control. Not just surprise. At first I was even misreading, thought it was Kelmomas who threw a chorae or something like that. But the way it’s written, unless I’m not mistaken, one of the skin spies whose hand was pinned down, supposedly because Kellhus controls all that domain and so “wills” those chorae down, manages to lift the hand enough to grasp the ankle of Kellhus. And for me this isn’t actually very consistent. Because I don’t see it as the natural consequence of surprise. It’s not something “more” (here too), something that wrestles control out. Kellhus is merely surprised by a new element in the picture, but none of this MOTIVATES the loss of control that could them trigger enough freedom for the enemy to launch an attack. I don’t see that surprise holding as a motivation, considering again how Dunyain think, the way their brain works, and how they master circumstances even in the event of something unexpected. I don’t see Kellhus as a possible victim of overconfidence. He could get frozen, but not moved back. It is just one small but crucial thing, that I’m not quite accepting.

But what the hell happened at THE END? This could easily be all about my failure as a reader. I just don’t know. I’ll say what I think I read. Kellhus was an impostor, in the sense that he was possessed. We know as much now. How? When? It’s likely it happened during the final part of book 2, when he got hung on the circumfix. It could be seen as a kind of threshold, but nor really if you think of it like a good/bad thing. The moment Kellhus willfully condemns Serwe is the moment he’s already quite the same his future self. So it feels like this possible possession doesn’t have a before and after, because the character evolved rather uniformly through the story. He slowly became, he didn’t switch at a single moment. But this has nothing to do with my bewilderment about the ending. The problem is that there are a number of sides, and they are all revealed sides …of the same thing. Kellhus was possessed by Ajokli, Cnaiur was possessed by Ajokli, strides onward to finally deliver murder to his enemy… Kellhus, who’s also Ajokli. Only to look up and see nothing because Ajokli that is Kellhus is already dead and the No-God is Kelmomas. What even is the supposed endgame? The “Mutilated” who “usurped” the Ark were just an intermediate step. The question was moved, not answered. They came in, and embraced the purpose of the Ark, the same as Kellhus accused his father would eventually do: embrace the same goal. But… THE ARK IS AJOKLI.

At some point it felt like it was a RPG campaign where the master is also playing all the players. A solitaire. Everyone is Ajokli, beside the rest of humanity who’s caught in a silly game.

Same as I read at the beginning of the book about “system initiation”, at the later point I also went reading about “the Ark”, see if the glossary had anything more to offer. And indeed there was. The entry opens about a debate. Whether the Ark is a spaceship, and so Inchoroi being “aliens”, or… something else. This is a part I didn’t understand. “Ajencis himself” (as kind of worthwhile authority, at this point) doubts and rejects the alien option. But I didn’t understand the explanation. “Since the relative positioning of the stars is identical in star charts inked from different corners of the World, we can be assured that the Incû-Holoinas came from someplace distant, but not far away.” …What? This is a pattern of confusion that repeats for me. Because there’s a level of “meaning” where you write fantasy to “expose” some meaningful concept of real life, but there’s also a level where you make something unreal, real. And so for example while souls are a fraud in the real world, and magic mere illusion, in this fantasy other world these two are both FACTUAL things. So what it is that is internally consistent as the cause of something different, and what is that it is instead hooked back in the real? In this practical case about Ajencis, is he fooled about lack of actual science available, and so his deductions being naive, or does he have a point I’m missing? The premise to that conclusion I copied, is that the stars hang as if from a canopy around the world. It similar to some Scylvendi story, in the first of second book. It’s kind of funny how revelation comes from something utterly wrong, but it’s beside the point there. Sailing the Void (space) versus sailing the Outside (the world beyond the world). What would be the problem of “sailing between the stars”? If I can’t make head of tails of what Ajencis deduces, the second part is something I can’t ignore. One of the fundamental aspects at the basis of the Blind Brain Theory, which is also the basis of the work here, is the concept of “sufficiency” and economy (effective heuristics, in a way). It’s one of the positive enablers. The fact that Bakker brings up that same concept here can only be interpreted from my point of view as something authoritative. He wouldn’t use this type of cue if he wasn’t trying to validate what was being suggested.

Even examining the alternative option, there’s nowhere to go left. It’s a dead end. If the Inchoroi are aliens, then we know the Ark was built by something that came before. Another darkness. Whatever happened on and to this alien world, who or what inhabited it, we have zero clue. There’s no point trying to speculate about something that is completely absent from the pages of the book. It’s a dry perspective. On the other hand the concept of Hell and otherworld has been quite prominent. And without an actual validation of something else, which there is none, the Outside is all that is left:

Given the evil, rapacious nature of the Inchoroi, the construction is typically attributed to Ajokli (fuck him in all its incarnations). Some even think the Incû-Holoinas comprises two of the fabled Four Horns attributed to the trickster God in the Tusk and elsewhere. Indeed, some Near Antique lays refer to the conspicuously golden vessel as the Halved Crown of Hate.

And so the Ark was… Ajokli again.

When the Mutilated take control of what’s left of it, they do not bend it to their own ends. Because their own ends are CONQUERED by the Ark. They end up agreeing with its mission, exactly as Kellhus assumed his father would do. But this again means that the Mutilated represented an unnecessary transition. From and to the same thing. Always the Ark, and always Ajokli.

Kellhus (Ajokli), the Ark (Ajokli), the Mutilated (Ajokli), Cnaiur (Ajokli).

What the Ark is even doing? Either sealing the world from the hell, so that Kellhus-Ajokli can deliver hell directly to this world. Or a contradiction. Or the last option, being quite plain an uninteresting: a group of oligarchs sacrificing everyone else so that they could save themselves. Just good old egoism and power grab.

What the hell is Kelmomas in this context? I did not embrace the way Kellhus was undone, but everything about Kelmomas becomes even more confused. Not in a mystical, suggestive kind of way, but just plain confusion. Kelmomas was… Ajokli?

Malowebi assumed, according to his terror, that the boy belonged to Ajokli… One of the Hundred stood manifest before him! Of course the boy was his!

Except that he wasn’t.

What was he, then? Why he could not be seen? All of this tells me I’m missing something plain, and it’s all my fault. But confusion piles up in a way I lose track even of things that weren’t confusing before. “Being unseen” was the action of the gods on the world. The White-Luck warrior, as a vessel of Yatwer. So this otherwordly essence give them a special quality. The Ark can not be seen, by the gods in this case. Why? Maybe because Ajokli found a way to hide it, his intention separate from other gods, maybe to seize control, and go against the God-of-gods as well? Sorweel was going to undo Kellhus, until Kelmomas intervention. In the same way, it is implied, the other side is also unperceived. I guess all Kellhus sons are included? Moenghus doesn’t count, and can’t read faces. Serwa was fooled by Sorweel. Everyone else never really faced a god, or god-like vessel. But it still makes no sense how these different special qualities are set. Isn’t Kellhus unseen by the gods because he got himself possessed? So how does it get passed over to his kids, who… cannot see each other? Or what? Which doesn’t even make sense since Kellhus just saw Kelmomas. His control “sputters”, but he does see Kelmomas. It’s “seeing” in a different way. There are so many aspects to this wholly practical problem that it’s both a large problem, and one that is not even interesting to solve.

While continuing to weigh on the rest… What’s the deal with both the No-God and God-of-Gods? Kelmomas is not born as a No-God (if so, why?), but there was the weird deal with the double personality with his brother. The way they get “split”, and the way Kelmomas then murdered him to re-appropriate the other half. Kellhus doesn’t say Kelmomas is mad, but that both of them surface and take turns. But where does this whole thing lead? It’s just another quirk of a quirky family? Everything about Kelmomas is a giant question mark. In the end he’s put in the sarcophagus because he’s just of the same blood. It’s a gimmick, there’s nothing else to it. So the No-God is what? Just a concept + a vessel.

WHAT DO YOU SEE?

The most ensorcelling scene from the first book and then onward. From the very beginning, and especially when the “I CANNOT SEE” part was added, it felt to me not like the authoritative voice of a god. But… a loss. A question not born of power, but of absence. It does make sense that it’s all a sublimation of someone entrapped within the sarcophagus. But… Once again there’s nothing more. The first time the scene is on the page tells everything it’s going to be for the rest of the books. Someone got entrapped in there, okay. Why? It’s a gimmick, need a special person to turn it on. At some point, maybe again the glossary, it’s as if this No-God lead armies and made tactical decisions. It always felt like bullshit and it seems confirmed here that the No-God is just a passive device that moves following some rules. But it doesn’t seem to embody any worthwhile “will.” Once again we get to a dead end, a concept that doesn’t resolve into anything.

At the same time, it throws a weird light on the God-of-Gods too. If Kellhus is an impostor, then Ajokli speaking is trying to manipulate the truth to something convenient. It’s evilness deceiving, the darkness turned light. But if then the GoG is not involved, this whole thing doesn’t leave it in a better place. The GoG does absolutely NOTHING. The most passive entity. While being absolved from the accusations, it also falls right into them. Whether a spider waiting to eat or not, he sits waiting. Just the same. Couldn’t be arsed by anything. What’s the deal with Mimara, then? (Her sections being written in present, rather than past tense, is one of many things I could have bet would receive an explanation in this book… Nope. Just a stylistic choice in the end, I guess.) The eye of the god is kind of stupid, and once again quite pointless. At some point the Eye opens and takes a stroll, recognizes already Kellhus a Ciphrang (as long Ajokli fits in that category?), then looking into Mimara’s womb and… is “struck blind.” I assume the living/dead kid separation is used symbolically to divide the before/after the coming of the No-God, since “the Boding.” Other than that, I suppose the eye unable to see is just a poetic concession to the unknown of a new life?

In the end both the Eye and the GoG do nothing and are nothing. It’s a device to expose the illusion. Even then, I understand the choice of making it an evocative scene. The “good ending” is so abrupt that is obviously a fraud. But there’s a physical Kellhus, or illusion of him. They come close to him. And then what? He’s a sarcophagus? But the sarcophagus is also up above, descending from the golden room. The idea of the sarcophagus projecting illusions is something new. Kellhus is dead. The No-God is Kelmomas. Why Kellhus is there, then? What do you see? What am I? It’s evocative. It’s also a powerful and deeply unsettling scene. But it feels more a special effect than motivation. It’s just there.

Those are some of the main aspects about the nature of the plot. I wasn’t persuaded by Kelmomas intervention, nor know anymore what is Kelmomas and why. Dragging along all the other gods like Yatwer, and all the side plot of Sorweel. Ajokli playing on roles on the table, without any plausible motive. Even less being actually meaningful. And there’s another minor quibble, the whole part of Serwa fighting the dragon. The only parts of the writing that felt incoherent for me where Kelmomas intervention, and the dragon fight. The latter feeling like something coming out of Sanderson’s Stormlight. Too fancy super-heroistic, and it seemed as if Serwa forgot she had sorcery replaced by… gymnastics? But the whole thing. The dragon waiting just behind the threshold. This is another part of the plot that went nowhere. In the end Kellhus goes in the Ark from above. Some other people do some minor infiltration here and there. Before opening the book, and then approaching the Ark and seeing it undefended I though all the second half of the book would take place inside the Ark, going deeper. But instead everything happens outside. And I forgot to mention: how the hell Kelmomas got in? We have books worth of proofs of how he’s able to lurk, and slip around unseen. But how does he enter the Ark, and how does he get inside the golden room? That was for me a bit too much of taking for granted. But anyway. The point is that they try to defeat the dragon and get inside for no purpose at all. Because the moment after it’s all done and solved without setting foot inside. It’s like filler, and it even gets mentioned as explicit speculation. Were they delayed so that they wouldn’t join Kellhus? Maybe, but it’s all pointless anyway. Why is Kayutas even in the books? He does nothing. Reappears at the end carrying Serwa’s very likely intended as dead. Both Serwa and Theliopa’s deaths are utterly stupid, beside also being meaningless. Another thing leading nowhere, chopped off without consequence.

(I guess Kayutas is also dead at the end, along with the rest of the host, given he has no sorcery and unless someone gives him a lift?)

All the while, Bakker was carried by his muse. The writing was inspired, and empowered by insight. It was about this, rather than that, but it was fully focused on what it wanted to be. While it was nothing about what I cared about, there were still parts that talked to me. When Kellhus faces the Mutilated, while it changes nothing in the story (as I said, it simply moves questions without answering them), it had a quality of being “meaningful.” At some point it’s written explicitly how this isn’t a simple dialogue taking place. When you put some people in a room, and they talk, rarely they’ll end up changing their ideas in a radical way. It’s the whole recurring theme of “Jnan.” What men do is bargaining, trying to find some advantage and using their ideas as a currency. It’s ironic what happens with Dunyains, because in their pursuit for the Absolute they become SLAVES to the world. They so much depend on circumstances, in ways even more direct. When Dunyains talk, there’s no jnan taking place. It would be just a waste of energy. Words and ideas are data. The truth is the bedrock of what is being said. They all share the same ground, no bargaining is possible. As it is written explicitly, anything can happen. Because there’s no defense from truth. They are all exposed to circumstance, to control NOTHING. It’s all about contemplation and awareness of what comes before. At that point, the whole interplay, is about who already has more pieces of the puzzle. Whose conditioned ground it is. This part spoke to me and rang more true than anything else in the book. The idea that anything could happen between some people just talking.

“I am the greater mystery.”

“I am master here.”

This makes sense if Kellhus is Ajokli, and the Ark is, indeed, his own conditioned ground. And maybe Kelmomas is just another unknown unknown. A fatal blind spot. Makes sense and is coherent with everyone else being fooled while being ahead. From Maithanet onward, but also including Survivor. There’s always a greater circuit and the Absolute just another fraud. But it’s all too vague to me, and kind of pointless. Ajokli being everywhere at once and not having discernible agency… and the whole concept of damnation.

It’s again something that I scribbled on the margins at the beginning of the book: if saving a soul is an individualistic goal, why does it become a collective effort?

It’s implied again and again that this is what matters, truly. What happens to your soul. Eternal damnation is the real motive, behind all the Inchoroi do and all the men of the Ordeal. The physical life is indeed nothing compared to eternal damnation, when eternal damnation is proven real. That’s the greater gravitational pull. But this world is so ravaged by HORROR that it seems to make no sense to me. I guess it’s the same as justifying a war, and yet wars happen all the time. Why would so many people damn themselves in order to buy a minuscule chance at salvation in some remote future, for someone else? Why if salvation and damnation are the only ends, so many destroy their own lives and damn themselves? Why fight for THIS world?

The plan of the Ichoroi is the most persuasive for that reason. If you don’t want to accept the implied “extortion”, the only option is to seal the horror away. Not embracing it. But it is incoherent because in order to seal hell away, they enact it where they are. They make the world hell, in order to be saved from hell, all the while damning and throwing themselves INTO hell. What is even the point, beside the Inchoroi being basically programmed to the task by instinct and so having very little say on their own choices?

In any case, all other options are shit. This is a world whose only answer is: FUCK IT ALL.

The only RATIONAL answer is Cnaiur’s. Unconditional HATE.

Not targeted hate. But worldborne hate. Dunyain hate. About the substance of the world. About the substance of the gods. About the substance of humanity. HATE IT ALL.

And again not hate that destroys and pillages, like in this case Cnaiur would do, but hate that despises participation. That simply renounces existence like “Survivor” had. A world not worth fighting for. Because participation is intrinsically enacting the same.

If anything, but without a single explicit point, this story answer is pacifism driven by HATE. Hate for the gods and the abomination they created as architects. Hate for humanity.

Achamian is caught in there like the idiot he is. First, he’s moved by narcissism. He wants to prove himself right. He wants to be vindicated. He wants the approval that he never had. A life spent not being believed and not being known. It’s funny how in the last few pages he becomes “himself.” First he’s completely flabbergasted, then Mimara shoves a fistful of ash into his mouth and he gets transfigured into Seswatha. He’s finally “home”:

“The Second Apocalypse is upon us!”

“Flee! Flee, Sons of Men!”

What cages Achamian to this shitty, pointless world is that he has a son. The moment he started dragging around Mimara, is the moment he either fucked up, or made the only meaningful choice. Both options being identical, just a way of looking at the same piece of the world. Who is so stupid to bear children into a world as shitty as this? You fucked it up. Good luck now.

While I accused Ajokli of occupying all places, it is made explicit that his/its goal (as Kellhus) isn’t the same as the Ark. When “offered” the coffin, he refuses. But what’s his own endgame, then? It is implied, contradicting again the above, that the Ark is not his craft. He is “master” on the Ark, indeed, but merely because to be used as a weapon against hell, the Ark had to use the same exploit that bore the Ark close to hell. And so vulnerable to its assault. The weapon to use against, became the weakness that opened a breach. What would be then the averted Apocalypse? The No-God not actually walking, but Kellhus being firmly under control of Ajokli? I guess the breach of the boundary. Bringing hell directly onto the world. So quite “bad.” What the alternative? On its own the Ark was meant to seal hell away. Which is ironically “good” …as long the process of delivery of that goal is ignored. The Apocalypse is therefore… “good”?

A level of silliness that can’t be put on the page:

“So a group of eternally damned souls, having no other fruitful option, decided to build an otherworldly spaceship to attempt flight from Hell and BACK into the physical realm, while carrying with them a wondrous device that would allow them to seal Hell away, given a large enough human sacrifice. So that they could enjoy a newfound autonomy. Turning eternal damnation into eternal orgy, I suppose.”

I guess there’s no supervision in Hell that prevents the building of spacecrafts? Or maybe they managed to steal one of Ajokli’s boats that he uses to go on vacation on Earth?

But why would the Mutilated be onboard with this plan, if the plan sacrifices all men (so including themselves) in order to save the Inchoroi? (see below where I complain more about this arbitrary racism)

Back to Kellhus, it seems going back to the fear of Achamian, that giving him the gnosis would be too much power, and a greater risk. The only thing Kellhus mentions confirms this, but feels quite hollow. I can’t even go in order through all the different problematic aspects. The Ark itself, as a device seems… racist? The most authoritative piece of information says the sarcophagus “is a prosthesis of the Ark” and that its function is to read a code hidden on the world that can only be detected through many deaths. And after reading this whole code the Ark is then able to “shut the world” against the Outside. All of these are arbitrary mechanics to the extreme. But IF this thing called the Ark comes from the Outside, as an instrument of the gods/Ajekli, why is it powered by “Tekne”, which is basically science? Why is the distinction alien/demons, that would be science/magic, get completely capsized, so that the demons use technology rather than sorcery? Why should a god invent science as a tool, within a magical realm, only to send a MAGICAL spaceship through some portal and crashing into the real world? This stuff is so convoluted that it does not make sense discussing about it at the level of plot, much less trying to extract some sort of relevant meaning out of it.

If it works is only in the scope of the truly alien from other planets, that would be quite shallow anyway, and also quite detached from the rest, as seen above. (There’s even a section, in some previous book, where it is explicitly said that this is not the first planet scoured by the Inchoroi. So while this is overall more coherent, despite the giant red herrings in the glossary, it is still the least interesting option and I’m not fond of dwelling more on it.)

“If the extermination of Men is your goal.” Told to the Mutilated… Aren’t the Mutilated ALSO men? Aren’t nonmen ALSO men? Weren’t the Inchoroi actually fighting nonmen during the first Apocalypse? Wasn’t Nau-Cayuti, as an ancestor to Kellhus ALSO a man? Isn’t Kelmomas ALSO a man? What is exactly is the PROFIT of sealing the world, if there’s no one left living to reap that reward? If the extermination of Men is the goal, then the Mutilated are going to toss themselves into damnation, only so that the world would be sealed right AFTER them. So in the end the world would be sealed just after all souls were moved to the Outside. A world “saved” by leaving it empty? Great job, you sealed the Outside from the other side. So that now you don’t have to worry anymore about eternal damnation, you’ve simply secured it perpetually for all souls existing. Even then, why the sarcophagus ONLY works with one of those specific ancestors? It seems oddly specific for either an ALIEN or otherworldly device that as to be built abstracted from its context. Unless you target it knowingly. But then how? Who?

(There are a couple lines in the book that appear as non sequitur. One is Kellhus mentioning some 144.000 something. I think a reference to that Inchoroi backstory that I forgot from some previous book, either 5 or 6. The other is that one of the Mutilated is immediately killed by Kellhus. He’s the only one who talks at that moment, but what he says is de-emphasized by the fact Kellhus only wanted four horsemen of the Apocalypse, but at the same time it seems blatant misdirection, that he killed that one because he mentioned something that he shouldn’t have… What he says is that “he” hides here. That “his siblings hunt him and he thinks he can hide from.” If this refers to Ajokli, then it could be quite important. Even if I really dislike having to chase the illusion of a major plot twist and explanation held up by a single line… It’s not enough to grasp. But if that’s true, how one of the Mutilated could have known such a thing? Simple deduction? It’s quite a stretch, but who are “his siblings”? The other gods? Is it a reference to Cnaiur? Or Ajokli itself is splintered in a number of independent selves who are competing while hiding behind the same surface mask? Again, it’s not enough to speculate.)

By the way, they removed the Chorae from the carapace to fit Kellhus in (he has sorcery). Then forgot to place them back, for Kelmomas (no sorcery). Why aren’t the Chorae back? Were they a simple afterthought?

“The No-God collapses Subject and Object”, yes, indeed, this is the Absolute by definition. Also the world. But also not. We know in this flavor of metaphysics the world is the will of the GoG (a rather crappy, lackluster will, if anything), who imposes a certain degree of stability and objectivity to the physical dimension. The Subject (or rather, subjectivity) is instead the domain of the Outside. Where it is more fragmented through the division of the various gods, each pursuing its own end and negotiating some relative degree of control (including, maybe, Ajokli power grab).

Thus… The GoG is the No-God. A contradiction. The GoG is not the sum of the gods. Therefore the GoG should be already the domain of the objective. Of the world for what it is. Without a soul, like our REAL world. Maybe you could see as an antithesis not of essence. So the No-God and the GoG are the same essence. But the GoG is over there, and the No-God is the physical manifestation on the physical realm. Even then, wtf Mimara was doing with the Eye of the God, looking at the No-God, so itself? And being horrified by itself?

There is no working angle to all of this that makes any sense for me. There’s the layer of the simple plot, the fantasy world as it is built with all its arbitrary rules that you read about and accept. And I don’t know what to make of it. And then there’s the layer of the symbolic and metaphoric, how you translate concept into a fantasy world in order to better expose some truths. Like Blind Brain Theory. And I DON’T KNOW WHAT TO MAKE OF IT. Neither layer leads anywhere intelligible.

WTF was the point? What it was that Bakker intended to do?

All this arbitrary application of devices, of arbitrary rules, of accepting this but not that, working toward goals that benefit no one or anything. Where this race has to be exterminated, but not that. We know the Great Ordeal moved on fraudulent ground, men were simply deceived. They were religious zealots, so whatever they believed had to be false on principle. But the motivations underneath, after you remove the deception and manipulation, don’t make any sense.

What world is the one where every option is bad? Where Ajokli conquered all options?

What was Cnaiur going to do? He walks toward the No-God, believing it be Kellhus. The horde parts before him, rather than assault. Because HE IS Ajokli, and if he’s who crafted the Ark, he is MASTER here. Or, if he’s not, he’s unseen. For whatever rules of sight apply, when Ajokli is not conjoined with Kellhus (but here there’s no reason why Cnaiur shouldn’t confer the same grasp on the sight, given that both Cnaiur and Kellhus are men). And then? Does he try to wave up at the flying carapace to be noticed? Does he try to jump and see if he’s able to reach it? Does he realize Kellhus is not inside and so he simply walks back? WHAT IS THE POINT?

WHAT DO YOU SEE?

WHAT DID I JUST READ?

I HAVE NO FUCKING CLUE!?

Bakker certainly doesn’t need nor deserve my mockery. But I have no fucking clue. As I wrote above, there is probably a lot that’s on me, as a failure as a reader. But usually I have some grasp or intuition. Not in the sense that I understand things anyway, but that there’s a certain known negotiation between what I did not understand, and what I think I can dig out, given more effort. It’s funny because it would be like measuring the breadth of a blind spot, which this story should have taught that you can’t measure what you don’t know. But this has usually been a working yardstick for me, a working heuristics. I have an idea of what a more careful reread could lead to, and I know that there are instead aspects of the story that I can’t argue. That there are no footholds and handholds. That there isn’t enough there that is usable to contribute meaningfully to these aspects I haven’t understood. Some of that end became a dull confusion, that didn’t coalesce nor suggest something meaningful.

System initiation. Resumption. Of what and why it is for me impossible to decipher. Much less “agree with.”

I could go back to look better at those sections about the dreams, the eerie tree that was mentioned both in books 2 and 6. The section after the head on the pole. But I know there’s not enough there. Not even remotely so. There is nothing for me that is usable in any way. Maybe I’ll change opinion but I feel like this is not for me something to re-read. I think I understood and taken away what I could, and probably more, given that I was familiar with the concept. Given that I already started again from book 1, so it was already a partial re-read.

In a world made of tier lists and best of the year, I’ll say that this as a whole is the most important thing I’ve ever read, and will likely remain so for whatever I’ve left to live. I guess that’s enough of a final statement, despite everything I wrote above. I’ll also say that Bakker is my favorite writer next to David Foster Wallace. This can be seen as a pretentious statement, of someone who’s trying to elevate one with the other through association, to better elevate oneself. But for me the two writers are actually very close. Not doing different things, standing at a similar height but on different pillars. There is something homogeneous, the way I see it (and isn’t Emilidis a little bit like James Incandenza, finding ways to break the world through artistic artifacts?). When I read DFW the first time, through The Broom of the System, the experience of reading had an unique quality. I felt changed while reading, and it was a lingering feeling that lasted a little while after I closed the book. It’s like being dosed on a drug, a physical sensation, but very subtle and fleeting. Distinct enough to be felt clearly, but still faint and impermanent. The EXACT same feeling I have reading Bakker. There is a before and after. A physical subtle shift, due to my way of getting tuned in. And yet again vanishing soon after. The Logos itself stays. The things being explicit. The ideas. But that subtle grasp and being tuned to that particular frequency is something that goes away not long after. Something that accompanied me through the months, through the last couple of years while reading all these seven books from the first page. That has been with me regularly, making my brain light up. And that I’ll now surrender because I know it goes away.

When I read Infinite Jest I dug a bit into a few things that were available. The ending to the Broom of the System was abrupt (much like the ending here, more similar to it than Infinite Jest). So abrupt that it has haunted me for a long time. I never dared re-read the book because I feared what I was NOT going to be able to find. A deep seated frustration for not being smart enough. Resenting that no matter the effort, it’s out of my reach. That the book is both for me and against me. I remember (vaguely) some note DFW wrote to the editor of IJ, acknowledging that the ending of the Broom upset the readers. And that he was going to do it AGAIN in IJ. He said that at the end the readers should know some 30% about one character, 60& about another, and 90% about a third. The way the book ends, both books, is deliberate. He had his reasons. DFW often said that readers shouldn’t ask him about IJ, because he cannot answer. Because the book was so sprawling and it went through so many editing phases and cuts, that the author simply didn’t know what got published in the end. His own memory was a fragmented mess of pieces. Whatever is the final book, he didn’t know and did not want to know. Even if the moment it was shipped it was what he wanted. That he gave it everything he possibly could.

Even still, the fact that DFW did not have a total control at the end, and that the editor messed with the thing and made cuts, left the door open to the idea of a mythical version of IJ, hidden away. Some book beyond the book, that was at the same time less and more. A mythical other half, written but not read. In Bakker’s case there’s nothing giving way to similar doubts and unfounded hopes. He said explicitly that THIS is the book he wanted to write. That THIS is the destination, the way he intended. When it was confirmed that the book was going to be split, as it was already expected, he said that this gave him one more year, possibly to continue working on the second part. He needed to complete the glossary, but still had enough time to revise and expand, if he wanted. He said explicitly that he decided not to. That he didn’t want to mess with what he had done beside fixing a sentence here and there. He was pleased. There is no other intervening factor, no editor who took over. Nothing else. This is his book and his intent.

It’s ironic that I think at some point before writing the last book Bakker did read Infinite Jest. And did not think much of it. For much of my failures as a reader, both on DFW and Bakker sides, I am the bridge.

Bakker could not see DFW, like a No-God. And DFW is quite dead, so who knows.

I can see both.

(I have not yet read the two stories that come after the end, set in ancient time, nor have dug into the glossary. That’s what I have left to read, but it’s unlikely that I’ll write about.)

(There’s tons of other notes I wrote that ended up not part of this, mostly about the broader overview and interpretation of the series as a whole, rather than continue arguing about the last few pages that make the ending. But I don’t have a way of fitting them here. It’s more probable that I won’t, as I’m already drained enough, but in the case I decide to write about that, it will be under a post titled: “We are all sranc.”)

Ongoing edit: One part of me would really like to move on, free my mind, because I’m tired and writing more is exhausting. But it looks like I’m not able to do it, I can’t move on. Right now I have at least three things building up on their own. 1, a post dedicated solely to the discussion of patriarchy and misogyny in the series, 2, a post dedicated to the decapitants and some interpretation of further possibilities and explanations of the end, 3, a large post of fragments of comments. As a large dump of everything I’m reading on the internet (ASOIAF forums are one of the sources I’m going through), as feedback on all the books, so that it can be cut and condensed to filter everything that I think is pertinent as analysis or commentary…

This final scene of Gravity’s Rainbow is not dissimilar to the endings of Pynchon’s other novels, which nearly all conclude in breathlessness, anticipation, or sublime silence. On the surface it is most similar to the conclusions of the two novels that precede it: V. ends in contemplation of the sublime and ancient waters of the Mediterranean, where the novel’s historical narratives sink from view having exhausted their symbolic resources. The Crying of Lot 49 is also brought to the edge of comprehension, though its mystery remains shrouded in the aura of expectation. Just wait! The word is about to be spoken; the sublime hesitation will break and the fullness of meaning will come crashing back in to dispel our partial paranoias and hypotheses.

The novel’s end therefore stands as an enigma—grammatically neither the ellipsis of Pynchon’s other endings, nor the parenthesis of his trademark musical interludes—which seems ready to announce some urgent truth only after its ability to be spoken has expired.

Quoted from here.