‘Who are you?’

‘He’s my friend, Lakoba,’ said Vishnik. ‘He’s from out of town.’

‘Anyone can see that,’ said Petrov. He turned to Lom. ‘And do you like this place? It is our laboratory. We are all scientists here. We are studying the coming apocalypse.’

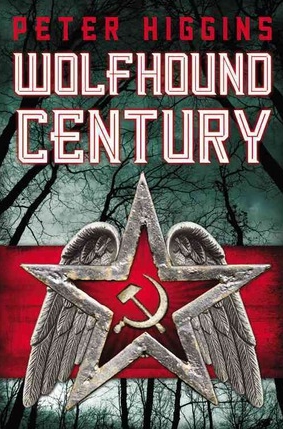

The original intention was to review this book about a month after it came out. Thinking maybe this would come under the radar, and so I could build some hype about it on my own. Instead here we are, a year and a half later, and the book that was rather well received by other bloggers. I actually had my eyes on this long before release. I had read the press-release back when Gollancz announced it. It’s been a few years, but the information written there was enough to wait with anticipation. A dystopian Russia, the idea of rich mythology and ambitious setting. Did the book deliver on those expectations? For the most part it did, though I have a number of qualms.

To begin with, this is a first volume in a trilogy. Since I’m late, the second already came out, and a third is planned for the first months of next year. The whole thing is finished and delivered, but deliberately split into these three books, released annually. The first qualm I have is about structure. I had it (and complained on Twitter) since receiving the book, and now that I finished reading it I still confirm all of that. The book is 300 pages. Probably less than 100k words, I haven’t checked. So it’s a fairly slim book for a projected trilogy and one automatically wonders why it wasn’t released in one volume instead. If the other two are of a similar size we would still be under 300-350k words (edit: the series is complete, total wordcount is 299k, also available on omnibus), and that is reasonably big. The other two volumes were done, so nothing was stopping the publisher to do it all at once. Moreover, these 300 pages are split into 83 chapters. Math tells me this means around 3.6 pages for each chapter on average, and they aren’t so densely written. So the result is a rather fragmentary kind of narration, something that resembles more a clogged, sputtering engine, than smooth, gentle sailing. This isn’t merely form, but also substance, because the way you choose to tell a story also gives it substance and meaningful structure. With a setting that is meant to be ambitious and original it is probably more effective to help the reader getting familiar with it. Instead it starts with pages filled with invented jargon or obscure Russian words and no direct explanation of what means what. It’s not necessary to understand immediately what everything means, because most of this is used as a smokescreen and atmosphere, to make you feel the world, making it a strange, mysterious and evocative place. So what you don’t recognize you’re meant to figure out by context, or by imagination. But all this, mixed with the fragmentary structure makes the beginning of the book hard to get into and enjoy. Instead of feeling immersed in a interesting world and let it soak, it feels more like seeing glimpses of it through a few cracks.

There are plenty of interesting aspects and themes to the book. Most of these are homages or “mirror images” of different books and writers. Some overt elements are for me blatantly Erikson-Malazan. There’s a giant god fallen from the sky, after all, and it takes possession of people to further his own mysterious agenda. Some other more abstract themes are also of a Malazan flavor, and even something in the writing style reminds me of it. Here’s a “warren”:

The buried chamber of the wild sleeping god was furled up tight but immense beyond measuring. The restless sleeping god, burdened with tumultuous dreams, had extended himself outwards and inwards and downwards, carving out an endless warren, an intricate dark hollowing. Its whorls and chambers ramified in all directions, turning and twisting and burrowing, spiral shadow tunnelings of limitless extent, unlit by the absent sun but warmed by the heart of the earth. It was all rootwork: the roots of the rock and the roots of the trees. It was matrix and web. Fibrous roots of air, filaments of energy and space, knitted everything to everything else in the chamber of the sleeping god’s dream.

Sometimes inspired writing, if abstract, and there’s enough of it in the book. But sometimes it also sounds a bit hollow and rhetorical, with flourishes that don’t hold too well. But not in an amount I found disruptive. It does not feel all faux and pretentious, or aimless grasping, meaning that the good parts aren’t simply there by chance: the writer is onto something. It’s worthwhile. Good qualities.

That’s important to me because the contrary happens when you strive for “atmosphere” without substance, and this book desperately tries to create atmosphere, over substance. So walking on a dangerous line.

But more than that, there are echoes of Harrison’s Viriconium and Gene Wolfe:

What he found was strangeness. Vishnik had come to see that the whole city was like a work of fiction: a book of secrets, hints and signs. A city in a mirror. Every detail was a message, written in mirror writing.

As he worked through the city week by week and month by month, he found it shifting. Slippery. He would map an area, but when he returned to it, it would be different: doorways that had been bricked up were open now; shops and alleyways that he’d noted were no longer there, and others were in their place, with all the appearance of having been there for years. It was as if there was another city, present but mostly invisible, a city that showed itself and then hid. He was being teased – stalked – by the visible city’s wilder, playful twin, which set him puzzles, clues and acrostics: manifestations which hinted at the meaning they obscured

The Lodka stood on an island, the Yekatarina Canal passing along one side, the Mir on the other. Six hundred yards long, a hundred and twenty yards high, it enclosed ten million cubic yards of air and a thousand miles of intricately interlocking offices, corridors and stairways, the cerebral cortex of a stone brain. It was said the Lodka had been built so huge and so hastily that when it was finished, many of the rooms could not be reached at all. Passageways ran from nowhere to nowhere. Stairwells without stairs. Exitless labyrinths. From high windows you could look down on entrance-less vacant courtyards, the innermost secrets of the Vlast. Amber lights burned in a thousand windows. Behind each window ministers and civil servants, clerks and archivists and secret policemen were working late. In one of those rooms Under Secretary Krogh of the Ministry of Vlast Security was waiting for him. Lom crossed the bridge and went up the steps to the entrance.

The Lodka cruised on the surface of the city like an immense ship, and like a ship it had no relationship with the depths over which it sailed, except to trawl for what lived there.

He let these thoughts drift on, preoccupying the surface layers of his mind, while the Lodka carried him forward, floating him though its labyrinths on a current you could only perceive if you didn’t look for it too hard. This was a technique that always worked for him in office buildings: they were alive and efficient, and knew where you needed to go; if you trusted them and kept an open mind, they took you there.

But these echoes are often less fertile, faint. In the end the city is the most powerful and interesting character. The atmosphere very dreamlike, with this idea of an anthropomorphic city that breathes, thinks, changes. That is alive. The style of writing matches this, trying to capture the myth in the air.

Everything was spilling myth, everything was soaked in truth-dream.

Anthropomorphic, sentient landscapes directly mean “myth”, things that acquire pure meaning, given voice. The setting of the book is some kind of middle world. It’s not directly fictional, in the sense that it does not read as an entirely fantasy world, and it’s not directly real, like some distorted historical fiction with fantasy injections. There’s no explicit reference at “real” history, but also no direct attempt to flesh out the world as fully realistic and self-contained one. What this is, is like the rest of the book, the whole of its structure: a mirror image, that sometimes blurs back and forth, between facts and dreams. Always in a kind of flux that transforms it. This atmosphere is plot, and that’s how I like things: not merely an “act”, but the actual point. It’s where structure becomes message, and so where technique becomes effective, coherent and coordinated with a well defined goal. So more than just “flavor”, even if flavor is what makes this book pretty unique and enjoyable to read. The setting is surely the king.

The other qualms I have are about characters and plot. Characters are for me a bit dull and drab, or stiff and apathetic. Not so engaging, emotionally or otherwise. They just hang there, sometimes the writing is more interesting than the character the writing is about. They aren’t mysterious in interesting ways, end up being rather predictable, and they aren’t relatable either. They don’t seem to have a life outside the plot and the short-chapter window they get. Events drag characters more than characters drag events. This can be a choice, but in this case characters just walk around passively, lead by “buildings” as in the passage quoted. Plot happens more because it’s written so, than because it is justified. I got the feeling like of an Herzog movie, the old ones where the actors are hypnotized, as if lacking life and agenda. They just follow a passive track, stuck in some sort of all-encompassing fatalism, or led by the proverbial god-hand (literally).

The problems about the plot are many, but can summed up by what happens in the last 100 pages: basically nothing of interest. The important characters even abandon the scene and are replaced by useless sidekicks. If the beginning of the book feels a bit like a prologue, this last third simply goes nowhere, has nothing to say. It tries to be urgent, but it’s the slowest feeling. The problem is that it’s so completely predictable and trite that the tension it tries to create is a catastrophic failure. Whereas the setting and everything under it can be seen as a kind of collage of countless pieces taken from different authors, but still ending up forming an incredibly original and interesting picture, instead the plot degenerates into a (somewhat) action B-movie of the worst kind that has literally nothing of value to say. It’s not written poorly, it’s just that it’s a bland, juvenile movie script of the kind we’ve seen way too many times. Absolutely zero surprises or even an ounce of actual originality. I’m going to spoil this because of how bad it is already: the last 50 pages are basically a fight scene against a Bad Guy, that when thought defeated inevitably rises up again, and then “falls to his death”, disappearing from sight and thought defeated for good, but still lurking as a possibility in the shadows, menacing to return in the sequel. And it’s even a terrible, terrible foe, with zero personality.

That’s why we are back when we started: the structure of the book. There’s a lot of stuff here that is actually good, and what I consider good potential. But then the last part of the book feels like an artificial attempt at creating a temporary conclusion (middling foe fought and temporarily defeated) to justify a split in three books. A movie script recreated by predictable scene after predictable scene. When I vehemently complained about this and accused the publisher of deliberately doing a cash-grab, they vehemently answered that this was none of their making, and that this was the author choice: the split in three books, the way he intended the thing to exist. I acknowledge that, but it doesn’t change the fact (or the opinion) that this split makes the book(s) weaker. Instead of what could have been a remarkable book, we have one that has many qualities that sink in the mud of predictability. It’s undermined. There’s not enough of the good parts to make it strong, because those foundations give in to a juvenile act, in the end. The fragmentary structure, and the short length, stop it from coalescing into something substantial, so it just stays there in potential, instead of actualization. A “pulp” novel that is less than it could have been. The setting is a delight, a mix of Clive Barker’s “urban fantasies” and Blade Runner, set in steampunk Russia, written by Gene Wolfe. Yeah, it would have been fucking great. It’s still worthwhile, but the implicit potential was, oh, so higher, and the writer shouldn’t have settled for just writing “homages” to his favorite books and movies. Or at least he should have done it less plainly, more cleverly.

If you want a

If you want a