Considering Westworld, The Man in the High Castle, and then Lost and its own rib, The Leftovers, but also that other stuff with Jason Isaacs like Awake, Touch and Dig. Or Upstream Color and Brit Marling’s own Another Earth… They are all more worthwhile to watch than The OA. (this is a reference to what I wrote back then about the first season)

(I’ve recently seen the three seasons of Travelers and that too is quite good and recommended. I mention it because it is also obliquely about the problem of epistemology)

I of course like and enjoy the “weird”, but only when it’s done well and those who do it know what they are doing, or at least sincerely try, like groping in the dark for meaning. Step by step. The earnestness of the struggle would be enough. The first season of The OA fell in this category and I still appreciate it. It was ambivalent, open, and it was quite “honest”, all things considered. There was a lot of worthwhile, well placed magic in that first season, and I was waiting this second one to see where it would all lead. In the end there wasn’t all that much to figure out. The show wasn’t a riddle to solve because it simply didn’t offer enough pieces to work with. It, in some way, “held itself back”, without really showing its hand. So I accepted it as a whole, as a kind of suspended thing that still worked on its own even if it felt also ephemeral.

The second season is somewhat satisfying in the sense that it offers a number of exhaustive answers to its mysteries. If season one held back and only hinted, season two instead is more blunt and explicit. The problem is that all these answers are very underwhelming and insubstantial in their meaning. The overall feel is that “the king is naked.” There are a few infodumps here and there, delivered by literal deus ex machina, and this foreign and unnatural source of information isn’t even the damning point. The problem is that when you brush away all these mysteries you are left with an exposed core that in this season is extremely emphasized to the point that it overwrites everything else: anti-scientific lecturing.

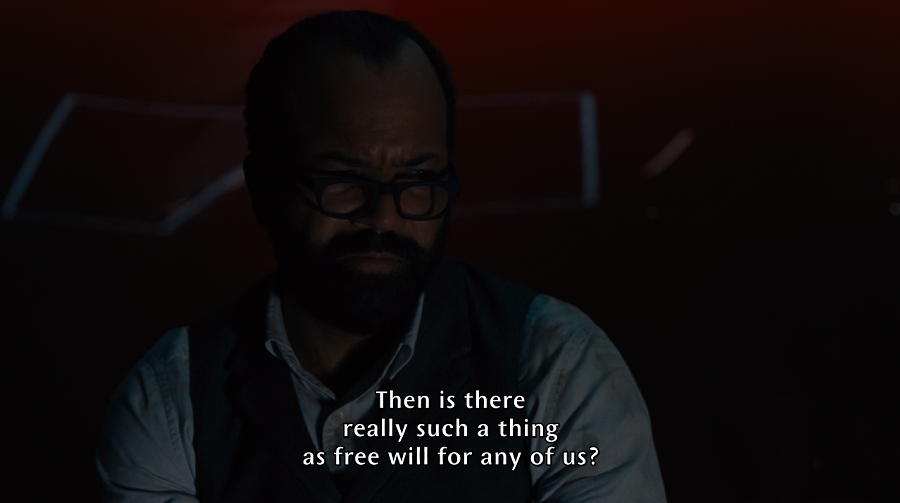

There is no way around this time. The character of Hap is even more clearly the straw man of science. This role is so heavy handed and unsubtle that this time it doesn’t work at all. There’s no nuance, no real complexity. Simply a cartoonish villain that at some point the show tries to re-enable through even more hokum.

This comes out after a little more than two years since the first season. I was really waiting for it because I had no idea in what direction it would be spun. This interest then increased because I read a few comments in the last few days calling it a “masterpiece”. Then I looked at the titles of the episodes and noticed one was “SYZYGY”. And I know what that is. Are they trying to blend in the mythology of the CCRU? Are they really diving into that stuff? Is that you, Nick Land? But nope, it was all for nothing. The “syzygy”, besides its very superficial and symbolic meaning, is used only as the name of a night club and then to solve a pointless riddle with no other ties. A macguffin that represents the great majority of the substance of this season. Inconsequential meanderings, looking for inspiration and ideas that just aren’t there…

That it is all largely pointless was quite evident from the first episode. This detective finds a riddle that reads something like “what’s above the sea but under the stars?” The detective comes up with a straightforward solution: “birds.” But it turns out it’s not the right one. At that point I stopped the video and tried to see if I could figure out another answer. I thought of consciousness, breath and stuff like that, but they didn’t quite fit with the five letters required. So I resumed the video to see where it all lead… Turns out the answer to the riddle is the code of an airplane that was flying over that specific location, that you could only see though the augmented reality app. This is quite exemplary because this riddle-house is one of the main themes of the season. Everything that relates to it amounts to nothing at all. Those riddles are so specific and so empty that instead of offering some insight, or a spark of intuition when you guess right, instead you are merely about guessing the arbitrary answer that the riddle-maker set up. The WORST kind of riddles. When the riddles are that arbitrary then there isn’t anything to them. No valid hints, no getting progressively closer to an answer. It’s all the random chance of ending on the same spot, looking at the same thing, and having the same thought of the designer. Pure coincidence. It’s predestination versus choice.

It then continues on this path of deus ex machina, “guess-what-I’m-thinking” pattern. The riddle house is a labyrinth without any direct or symbolic significance. It’s just that, a labyrinthine labyrinth that delays its solution until the very end, just in time for the necessary twist to end the season. And the solution is lame outside those 20 second when the post-modern layer drops. The “behind the curtain” moment is always cool. The fourth wall breaching. But if you have at least a little experience with it then you’d expect at least a tiny bit more than it simply being shown. Here instead it just goes nowhere. The OA can travel through dimensions, so why can’t she travel to a dimension where The OA is being made as a TV show? WHOA! Whoa… Well, alright. Is that really it? Nope, because they drop the ball by making it a fictional semi-reality. Where Brit Marling is actually married to Jason Isaacs and gets hurt during the finale while it was being made. So it’s not quite here, but almost. Am I supposed to be impressed?

So yes, the fourth wall breaking is always quite effective because you don’t expect it. And to the general public of Netflix it might also look like a shocking plot twist. But it is a known tool. You have to give it some purpose, make something out of it. There’s nothing here beyond that cheap surprise. It’s just sleight of hand for its sake, that it works because it simply aligns with the perspective of the show where multiple realities are an established mechanic. So why not? Because there’s nothing else to it. There’s nothing implied, nothing “truthfully magical.” There is no beyond, no revelation, no transcendence, no understanding. It’s a labyrinth that the showrunners couldn’t solve. It’s a closed loop without emergence. It ends flat, monotonous. It sinks.

Instead of understanding that mythology and using it to show the way, it falls into its trap. Fails to see ahead, to see clearly.

The enchantment that worked for the first season simply wore off, now the king is stark naked.

And again, the problem isn’t that nakedness. The problem is what’s left after you remove the game of mirrors and pretense: that anti-scientific core. The message couldn’t have been emphasized more. The king is not only naked, but completely blind, and he made his blindness a virtue.

Like in Twin Peaks, this show is itself condemned to OBSCURITY. That last moment when Laura Palmer SCREAMS. She’s lost once again because she’s trapped inside (inside fiction, worlds). Part of this loop that cannot be shattered. NO MATTER HOW MANY TIMES Cooper tries to save her, traveling to other dimensions. Do you see the parallels? The OA is Laura Palmer, and she can’t save herself because she IS blind. She never got any insight because the show as a whole has made the gnostic obscurity its idol. You cannot awake if you are structurally blind, not able to see the forest for the trees. No help outside nor within. There’s nothing else but surrender to the blindness itself.

This celebration of gnostic blindness couldn’t be more EVIL because there’s no Cooper fighting against it. Instead of fighting darkness, it’s a celebration of it. It’s blissful nihilistic abandon to a false sense of truth. Like moths flying around an artificial light. The show essentially incarnates the enemy it pretends to fight. It blindly states that it lost the capability to navigate the space. It permanently lost orientation. A victim with no salvation. A prey to the higher forces. No choice, no will. Just a prey that cowers and wails.

The OA is the blind loop that in Twin Peaks Cooper tried to shatter. A cage. And if Twin Peaks ended with the perpetuation of that endless “chase”, maybe The OA embodies better our modernity. Because it idolatrizes blindness itself and shows that human beings are structurally unable to navigate the space. They are broken in a definitive way. Structurally broken in a way that salvation is simply not possible. There is no narrow bridge to cross. No journey to go through, no lesson to learn. There’s only the desperation that drives you deeper, closer to the ultimate damnation. There is no hope. There is no choice. And there is no understanding possible. You die, and die blind.

Here is where we go a little deeper, because this pattern of chasing after blindness isn’t new. And it happens in the show because the show comes from that same angle where blindness is always sublimated. What it would be? Idealism of course. That gnostic blindness mistaken for “light”. The power of the soul. Of this anti-scientific false idol.

(continues here)