I’m at about 140 pages into Martin’s A Storm of Swords and once again wondering about the causes of its popularity. I know that this third book is considered by far the best in the series, and that I have to expect things slowing down quite a bit in the next two books, so my expectations here are set very high, maybe that’s why I’ve found those first 140 pages not as the best prelude to the best book. The plot is stuck at the end of the previous book, and Martin needs all those 140 pages merely to go through each PoV to make a summary and set a new starting point.

That’s how you can write a huge 1000+ pages book and still give the impression that not much happened. The structure is rather simple, you have an average of 10-15 pages for each chapter/PoV and it takes about 150 pages to return to one. In the end this produces a 1000 pages book where a single PoV has about 100 pages of available space to tell its story, and 100 pages is the bare minimum to show some development, especially with the kind of detail that Martin writes in. That’s the formula to write these epic sized fantasy books. Just an high number of PoVs, fragmenting the story, but also offering that big breadth one expects precisely from this genre.

My question is why Martin and Jordan series were able to reach a huge popularity and the answer I offer is that both do something similar but from two different angles. I think the keyword is “accessibility”. Martin is popular because his series is what you can easily recommend to all sort of readers. That’s why it’s successful: because it’s a genre novel accessible (and written for) all kinds of readers. You don’t need to be a “genre” reader to engage with Martin story, and so this series can tap into the large audience of general readers.

Whereas Jordan retains a similar level of accessibility. His series also taps directly onto a huge pool of readers: all kinds of adolescent readers. The Wheel of Time has the power to engage all sort of “younger” readers. It’s like a LotR where uncool, clumsy Hobbits are replaced by young future heroes destined to conquer and change the world, becoming celebrities. Because of how it’s built, its strength is about tapping onto a certain audience, in a specific age-range but regardless of whether they are “readers” or not. Or even genre readers. The WoT can convert someone, making him a “reader” in the first place, and a “genre” reader as consequence. It does so because it offers characters and themes that appeal directly to that age-range, it’s the call of the adventure and the writer taking the reader’s hand, offering one of the most immersive and engaging experiences. It’s the stuff younger readers dream about, and it fully embraces it. It gives them the time of their life.

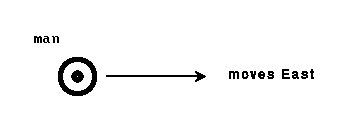

That’s why I used that distinction between “adult” and “young” fantasy. Martin’s series can be seen as representing “adult fantasy” that is extremely popular and successful because it can CONVERT adult readers into “genre” readers. On the other hand Jordan’s series is also hugely popular and successful because it converts readers, but in this case it’s more carefully aimed at an age range. What ASoIaF does for a more adult public, the WoT does for younger readers, recruiting them into “genre”. In both cases, these two series can rise so much in popularity because they draw from a huge pool of readers that aren’t limited by “genre”, and that’s why I’m putting the focus on “accessibility” and “conversion”.

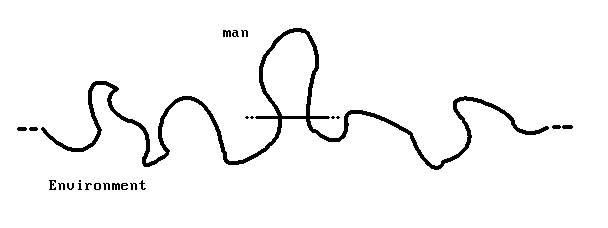

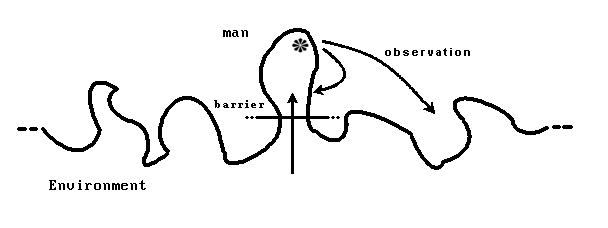

There’s finally another element that plays an important role in all this. It’s usually the writer’s job to engage the reader and make him “care”, keep him reading and turning the pages. But I think this is an illusory description because it overestimates (and romanticizes) the writer’s power and ultimate goal. I think in the best case the writer can only work on the illusion of directing and manipulating the reader’s interest, while it’s probably more correct to say that the writer merely taps and rejuvenates interests that have always been there, with the reader. Like suppressed memories that seem to resurface unbidden. It’s a much more subtle touch, and far less powerful. More sleight of hand than magic.

So why is this sharing of interests important in the case of popularity of these series? Because it’s the real hook that makes possible to reach for that huge pool of readers. Think to Martin’s series. Or even “Fantasy” in general. The common response you get from non-genre readers is: why should I care? Why a normal adult guy who has more immediate concerns should waste hours of his life reading “fantasies”? That’s why the common answer is about conflating Fantasy with “escapism”. It’s the most immediate reaction. But this is also the key to interpret how Martin’s series can be so hugely successful at engaging readers who usually “do not care” about Fantasy. What’s the First Mover in Martin’s series? Family. If you think about it, that’s the whole core. That’s where his series sets its roots. That’s the link to readers who aren’t normally genre readers or have zero interest in reading genre fiction. Its strongest theme is immediately familiar. All the priorities of each characters are simply defined by where he’s born, that will then also define what place he’ll have in the Big Game. Martin has an archetypal grasp on what everyone cares about, and so the possibility to connect with all readers. The first generalized hook that powers the series is about family concerns, mothers worrying about their children. It’s universal even if it’s encased in “fantasy”, and it can immediately engage readers because of its familiarity. The “adult” aspect is merely related to a style. Martin’s series is built on PoVs and these PoVs are selected on a wide range. It’s “adult” because it requires to shift these projections, have interest in this wider range of perspectives, in their breadth and diversity. Adolescents are usually more narrow-minded and self-absorbed to care about what happens outside of themselves (and the WoT reflects this). Then Martin builds the structure of his game by giving voice to different sides, creating contradicting feelings in the readers since there’s not a privileged side the reader can be on (though this is mostly a well crafted illusion).

Compare all this to Jordan and you see why I brought up the “young” angle. The WoT targets younger readers exactly because it selects its PoVs within the narrower range of its expected audience. It more immediately offers PoVs that the reader can recognize and identify with, offering themes that are strong specifically for that audience. And then it at least tries to follow those readers as they get older, by trying to broadening the range of the story. So the WoT is the ideal journey, recruiting and converting “young adults” into faithful readers, and then trying to walk with them into their adult age. That gives enough universal power to explain the popularity.

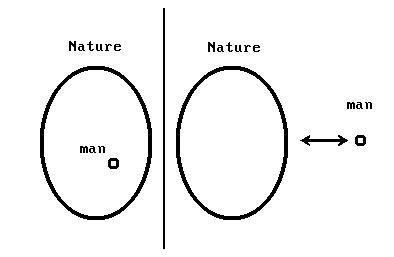

Now consider Tolkien. In this case Tolkien wasn’t writing for a pool of readers already waiting in potential. He just chased his own interests. This is important because “The Lord of the Rings” isn’t an “accessible” book at all, and so this seem to break the pattern I described above. It’s true. LotR is actually way more “niche” and less accessible than both ASoIaF and WoT. It’s far less easy to pick up and enjoy. And it’s also not a book that easily converts readers that do not have a specific interest in the genre. So why it’s still so hugely popular? Just because it came first? I don’t think so. The reason why Tolkien remains so popular while not being accessible is, the way I see it, because there’s a huge cultural push that overcomes Tolkien’s accessibility issues. His world is now part of mass culture, and being so it means EVERYONE is exposed to it. There’s pressure that comes from general culture that goes in Tolkien’s direction, and so all kinds of readers are pushed in this direction. Works like The Silmarillion are still extremely popular if you consider how nigh inaccessible the book would normally be, impossible to sell commercially. But this happens solely because there’s a general culture push that makes readers overcome those barriers.

Consider Malazan. Malazan, compared to ASoIaF, isn’t easy to recommend at all. It has humongous accessibility issues. This is usually blamed on the “medias res” style of the first book, but I think it’s a wrong angle. The problem with Malazan accessibility is that it’s much harder for a new reader to care about. It takes maybe two chapter in ASoIaF for the reader to figure out what it is about. One chapter in the WoT. Only the Prologue in LotR to set the style. With Malazan the reader feels like hiding in the shadow and chasing after someone on his own obscure agenda. Erikson doesn’t take the reader’s hand and gently leads him on the journey. There are no immediate rewards. You just follow with your own determination, if you want.

Why should a clueless reader care? What’s the big motivation that makes someone pick up a so huge series and overall commitment? But that’s just one aspect. Another crucial one is that all Malazan qualities generate big contradictions. The first book already presents things on a scale that dwarfs most other fantasy series, pulling out all the stops. Then by the time one reaches the third book that scale grew EXPONENTIALLY to levels that are utterly unimaginable. Just unprecedented and with no parallels. And yet, this is counterbalanced by another side that’s deeper, serious and incredibly ambitious. Giving the idea of something that takes itself very “seriously”. This creates different angles that can explode into a strong contradiction. On one side you have readers who engage with the most overt aspects of the series, the breakneck pace of the plot, the insane power levels, great battle and big scale spectacular stuff. The more mindless fun and shiny stuff on the surface, if you want. And then there are readers who instead find all that childish genre reading and instead expect something more “adult” in ASoIaF style. Ideally, one would say that Malazan is a distillation of the best of both worlds, and then even goes its own way to achieve something completely new. But far more commonly readers come with their own set of expectations and what happens is that the average reader is killed in the crossfire of contradictions. “Adult” readers can barely suffer through few pages without branding it as nigh incomprehensible childish fantasy gibberish, while those who are in for the “fun” and immediate pay off felt bogged down later on when the story reveals a depth and requires the reader to engage with more than just the surface. This ends up giving a general and immediate picture of having the WORST of both worlds. It wants to be serious and pretentious, while instead being juvenile and terribly chaotic and rambling. A puzzle that can’t be assembled.

How could Malazan be more successful? Why should the average reader care? It’s definitely NOT aimed to readers who aren’t already “genre” readers. You could maybe picture some serious-looking university professor reading a copy of Martin’s series, but could you imagine him reading Malazan? You need to be part of that inner genre group to even be a potential reader. This already makes the pool of potential readers exponentially smaller. It’s already a niche with a niche interest. And then you can imagine where potential readers come from. Maybe they read on some forum some readers who say how Malazan is so much better (it’s rare, but it happens), and so they approach Malazan expecting something that can compare to ASoIaF. And are immediately turned off by how “genre” Malazan is. Ultimately it engages with a number of themes that aren’t exactly that broad in appeal. There’s very little of those immediate and familiar feelings that give ASoIaF its strength. Malazan is less a traditional narration sprinkled here and there with fantasy elements, the way ASoIaF is. It grasps and deliver what the epic genre is, and why its powerful. It knows where it comes from, and has no identity crisis, or narcissistic pretenses of being appreciated by “everyone”. But then it requires a reader with a very open mind, who can take the challenge of the big commitment and that doesn’t ultimately jumps to conclusion because the book betrayed this or that expectation. The wider the range of interests, the more chances to appreciate Malazan in all its aspects. But this really ends up producing readers who are me, you and a few others. You have to have already developed an interest on that stuff, and the open mind to fully enjoy the “young” and “adult” parts without the feel that they clash horribly with each other.

Finally R. Scott Bakker. He suffers even worse from what I described about Malazan. Even more you have to share the writer’s interest on those specific themes and angles he brings up. Even more his series is precisely aimed, with a very strong thematic focus. This focus is nowhere what you expect to reach a general public, the same as you don’t expect the general public to read his blog because of the content he puts in it. It’s simply stuff not planned or meant to tap onto a big pool of potential readers. If it becomes popular it’s simply because it’s so unique and exceptional that it becomes easily recognized, and so not swallowed in mediocrity.

But what happens then? That lots of readers, all kinds of readers, hear good things and so try Bakker’s books. If they don’t have a serious interest in those themes Bakker offers then they end up noticing just the violence. The violence becomes the point. The edginess, grittiness and all those things that are today negatively branded as “grimdark” as well epitomizing all the problems about misogyny and whatnot. This produces an overall hideous image of Bakker’s series. Seen right now on a forum: “It’s an endless parade of fantasy name salad combined with massive ruminations and internal monologues.” And that’s a positive side. Otherwise it becomes an accusation directly to Bakker of being an horrible human being. Why does all this happen? I think because once you “remove” that deep layer that Bakker engages directly (and it happens whenever a reader “doesn’t care” about that stuff) then only the violence and the ugly remain. They become the one aspect monopolizing the attention, without understanding that all that is built IN SUPPORT of the rest. One element observed in isolation from everything else, and the result is readers who end up feeling offended by what they are reading.

All this to say that it’s all a matter of aims. How big is the pool of readers you try to reach. And matters of “quality” don’t even prominently come up. Only huge cultural pushes can overcome a narrow aim, like in the case of Tolkien. Another example is Neal Stephenson. He also has a very narrow target, writing for those who must already have a serious interest in the things he deals with. Yet he can be so successful because the kind of “geekdom” that makes his public nowadays is so common and widespread that it also became a “general public”, creating a cultural push that isn’t so far from what I described about Tolkien. It’s a wider movement of general culture that makes niche themes become more widely shared.

But I think that at least for the foreseeable future the very big splashes of success (here I think even about the Harry Potter, Twilight or Hunger Games) will come from traditional and familiar narratives sprinkled by “genre” elements. Ending up with a broadening of the genre, indeed, but also reducing the genre to innocuous window dressing. That’s always the risk when some smaller cultural movement is swallowed whole by the mass culture…