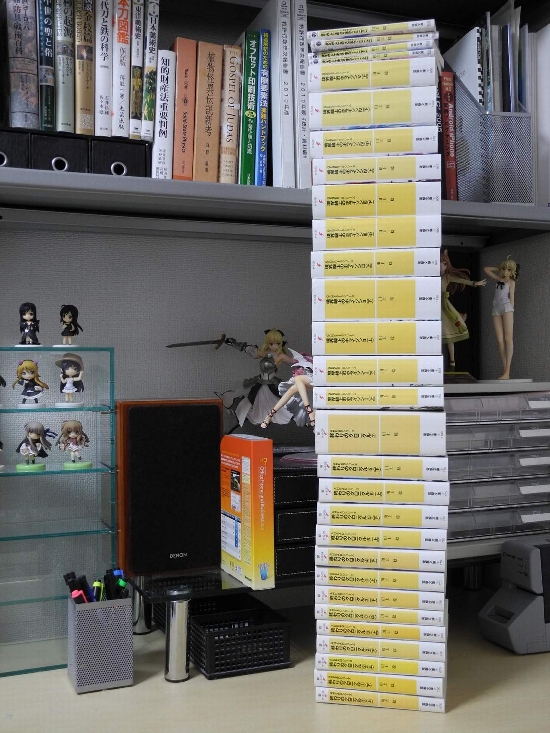

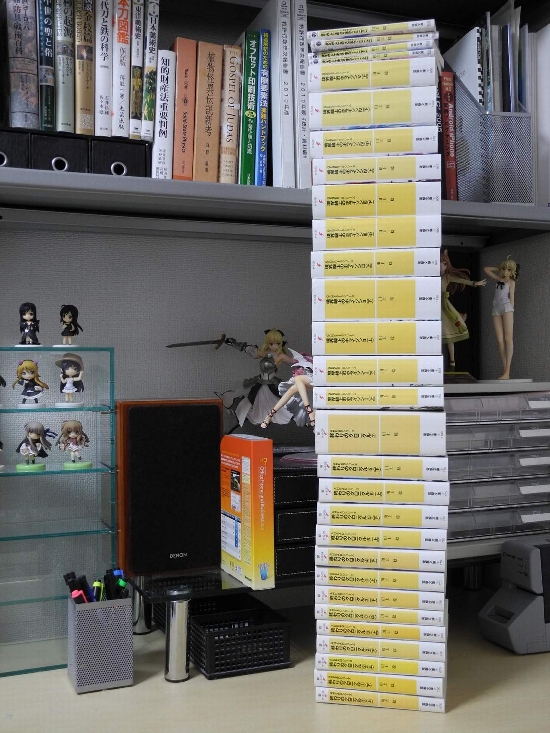

You thought the Malazan or Wheel of Time books all piled up are an impressive sight. Now look at this Epic Stack:

Edit: This picture is outdated. Look below for updated numbers and a good estimate in english wordcount. The Otaku Tower just grew some more. You can easily double what you see in this picture since it misses 12 more big volumes, 15 small ones of the City series, plus an handful of minor ones.

While not “technically” one series, it’s still a story in the same setting written by one guy (actually it’s a ‘she’, I think), and what you see is not even close to being done since the upper half is, accordingly to its writer, just 1/4 of the planned whole. The first half, from the bottom up and including the first bigger volume, is the first completed “series”, a sort of prequel, then from that point all the way up it’s a new ongoing one.

These being Japanese “Light Novels”. Or what you could (vaguely) consider as the Japanese version of “Young Adult”. Most of anime these days are either based on light novels or visual novels (these, too, of fairly epic length, since we’re talking about reading on screen for 50+ hours, with fancy music in the background and most of them also with fully voiced dialogue).

Usually they are dialogue-rich (terse on prose) and tell exactly the kind of stories you’d find in anime. School life mixed with fantasy stuff and so on, but also hybridizing with all kinds of genres. Being very long series with many volumes is the norm, though it’s rarer that the volumes are as big as some of those in the picture and you could expect the standard being around 50-60k words. Lots of these are also quite decent, or at least fun to read. And many are also available in English, one way or another (though it’s only a tiny amount of the total Japanese market).

One way for example is the Haruhi Suzumiya series, which is one of the most popular. The series is currently at 11 volumes in Japan and it will be complete even in English within this year. These are from “Little, Brown Books” and rather cheap even in the hardcover version (about $13 each). But in this case these are smaller “novels” of about 200 pages. Or ranging from 40-90k words. Basically the size of Neil Gaiman last “novel”.

The other way instead is thanks to fan translations: http://www.baka-tsuki.org/project/index.php?title=Main_Page

For example all 30 volumes (edit: we’re at 40 now) of very popular “Toaru Majutsu no Index” are fully translated, available for free in a number of formats. Other stuff like the series written by NisiOisiN has instead more “literary” ambitions and harder to translate, especially because of excess of wordplay.

Edit: his most celebrated series, “Monogatari” is now being officially translated. Kizumonogatari was the first in English even if in Japan it came after Bakemonogatari. Bakemonogatari itself instead was split in two volumes in Japan, and three in the US.

01 Kizumonogatari December 2016

02 Bakemonogatari Part 1 December 2016

03 Bakemonogatari Part 2 February 2017

04 Bakemonogatari Part 3 April 2017

05 Nisemonogatari Part 1 June 2017

06 Nisemonogatari Part 2 August 2017

07 Nekomonogatari Black December 2017 -> LE Box set

08 Nekomonogatari White January 2018

09 Kabukimonogatari April 2018

10 Hanamonogatari June 2018

11 Otorimonogatari August 2018

12 Onimonogatari October 2018

13 Koimonogatari January 2019

14 Tsukimonogatari March 2019

At that current planned point we’ll be at 14 of 28 novels out in Japan, with more planned it seems. The catch-up will take some time.

Disclaimer:

NISIOISIN’s writing is pretty complex; the dialogue he uses contains a lot of Japanese wordplay (such as puns on different readings of kanji, that simply cannot be translated to English), layers of Japanese cultural references (anime, manga, TV shows, folklore, etc), and very little third-person narration to indicate who is speaking when, often leaving the reader to infer which characters are talking during long dialogues.

Bakemonogatari is also being adapted to anime by the best anime studio around, SHAFT, and putting together normal anime episodes to the actual movies, you are looking at something around 30 hours long total, or around 100 episodes total, since every episode is 20 minutes on average. (Kizumonogatari, the actual first novel to come out in the west is being adapted to anime last, as three movies, each part about 1 hour long, so three anime episodes bundled together)

Another nice schema on Monogatari complex structure, for both light novels and anime.

The bottom line is that while it’s all stuff targeted to a specific public, it also has a kind of fresh and insane creativity that you probably can’t find in any other medium. Though you’d probably have better luck going through the Visual Novel side, like Fate/Stay Night (expect about 60 hours of your time), or Ever17 (closer to 30) and Umineko (close to 80 hours, and beware the Steam version, it needs fan patches to add the full Japanese dialogue voices).

About the Epic Stack above, here’s a page attempting an introduction to the world, even if I think it’s more from the anime side, at least it gives an idea of the kind of crazy to expect: http://randomc.net/2012/06/30/kyoukai-senjou-no-horizon-retrospective-part-1-the-premise-the-world-episodes-01-06/

This is the cover of one of the last volumes, which I won’t comment:

https://www.baka-tsuki.org/project/index.php?title=File:Horizon3C_cover.jpg

And this is another slightly more proportioned…:

https://www.baka-tsuki.org/project/index.php?title=File:Horizon4A_cover.jpg

If you instead are ready to begin reading it, you can start from that tiny volume at the very bottom of that huge stack, right here:

http://www.baka-tsuki.org/project/index.php?title=Owari_no_Chronicle:Volume1

—

UPDATE: I’ll keep this updated section with new stats about this project.

There have been three different main series part of the same universe/project, that is actually structured into six phases. The phases in their internal chronological order are: FORTH – AHEAD (Owari) – EDGE – GENESIS (Horizon) – OBSTACLE (Hexennacht) – CITY. In the image you can see the first series to come out at the bottom (but City phase, so the last), Owari in the middle (but the first in the internal order) and Horizon in the top line (the last being written, but the middle one in internal chronology), but the image there obviously only shows the first 11 volumes of Horizon, and we’re now up to 29. And in the last year, ongoing along Horizon there’s also the new Obstacle series, that seems to shift tone toward a “magical girl” type of story.

This is the output in release order:

– “City” series (1996-2002) 15 volumes

– “Chronicle of the End” (Owari) series (2003-2005) 14 volumes

– “Horizon on the Middle of Nowhere” series (2008-2018) 29 volumes

– “Forth” (Rapid-fire King) series (2013) 2 volumes

– “Clash of Hexennacht” series (2015-2017) 4 volumes

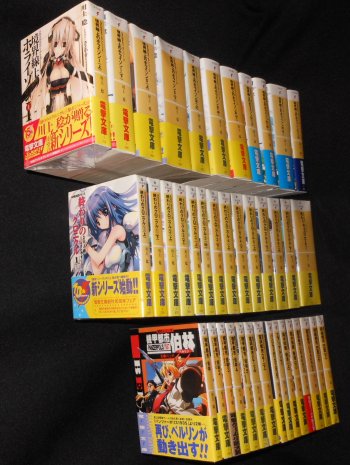

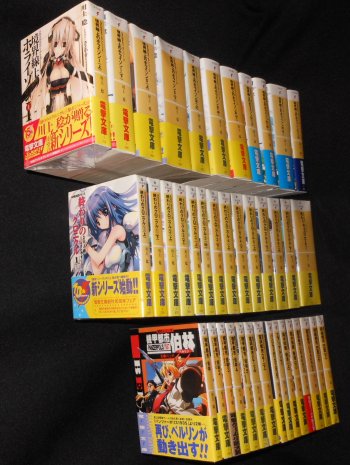

Another image. On the right there are again the 15 volumes of the City series (top to bottom, in order), the highest pile is again the first 13 volumes of the main Horizon series (the lighting symbol), with 8 smaller volumes on top that represent the “Kimitoasamade” side stories. Then the 14 volumes of the complete Owari, and finally on the left the two volumes that up to this point represent the entire “FORTH” part of the story, released in 2013. So this image represents the full cycle minus the four Hexennacht volumes and 13 of the latest Horizon. and it’s also put in chronological order: Forth (2 vol) -> Ahead (14 vol) -> Genesis (13+16 missing vol) -> (Obstacle, 4 missing vol) -> City (15 vol)

Here instead you can see all the released Horizon series, all 23 volume of it. The front row is what is available in English fan translation.

These are some stats about wordcount. I’m using the English fan translation (e), for the rest of the Horizon series I’m using estimations based on averages and the number of pages (not accurate but pretty close). It’s likely that the whole thing up to this point is around 5.5 million words total.

City Series (English only)

1) Panzerpolis 1935 | 43k

2) Aerial City | 47k

3) Tune Bust City Hong Kong A | 50k

4) Tune Bust City Hong Kong B | 49k

5) Noise City Osaka A | 58k

6) Noise City Osaka B | 65k

7) Closed City Paris A | 80k

8) Closed City Paris B | 76k

9) Panzerpolis Berlin 1937 | 57k

10) Panzerpolis Berlin 1939 | 59k

11) Panzerpolis Berlin 1942 | 58k

12) Panzerpolis Berlin 1943 | 58k

13) Panzerpolis Berlin 1943 Erste-Ende | 65k

Current total: 765k

Owari no Chronicle (Completed in English)

1) 1A 78k 386(pages) (10 June 2003)

2) 1B 88k 450

3) 2A 67k 386

4) 2B 83k 482

5) 3A 71k

6) 3B 67k

7) 3C 88k

8) 4A 94k

9) 4B 96k

10) 5A 93k

11) 5B 101k

12) 6A 102k

13) 6B 104k

14) 7 165k (10 December 2005)

Total Owari: 1M 297k (e)

Kyoukai Senjou no Horizon (now using x164 for estimation)

1) 1A 116k (e) 543 pages (September 10, 2008)

2) 1B 148k (e) 771 pages

3) 2A 178k (e) 905 pages

4) 2B 220k (e) 1153 pages

5) 3A 136k (e) 737 pages

6) 3B 150k (e) 833 pages

7) 3C 158k (e) 897 pages

8) 4A 112k (e) 673 pages

9) 4B 135k (e) 737 pages

10) 4C 177k (e) 993 pages -17

11) 5A 118k (e) 712 pages -21

12) 5B 162k (e) 1000 pages -34

13) 6A 115k (e) 712 pages -24

14) 6B 116k (e) 840 pages -48

15) 6C 175k (e) 1064 pages -33

16) 7A 137k (e) 808 pages -21

17) 7B 141k (e) 824 pages -20

18) 7C 175k (e) 1016 pages -24

19) 8A 118k (e) 744 pages (February 10, 2015) -27

20) 8B 135k (e) 824 pages -26

21) 8C 172k (e) 1000 pages (June 10, 2015) -24

22) 9A 140k (e) 808 pages (April 10, 2016) -18

23) 9B 165k (e) 1000 pages (June 10, 2016) -31

24) 10A 130k 792 pages (October 7, 2017)

25) 10B 151k 920 pages (December 12, 2017)

26) 10C 174k 1064 pages (March 10, 2018)

27) 11A 145k 888 pages (July 10, 2018)

28) 11B 158k 968 pages (September 7, 2018)

29) 11C 190k 1160 pages (December 7, 2018)

Total Horizon: 4M 347k

Clash of Hexennacht

1) 59k (e)

2) 60k (e)

3) 64k (e) (10 September 2016)

4) 69k (e) (8 April 2017)

Total Hexennacht: 252k

—

This was originally posted on Westeros forums. The interesting thing is that it spawned a discussion that turned down into racism and dismissing the whole genre of Light Novel as rubbish. Which is interesting because, once you take out the specifics, it’s the exact pattern you can see with “genre” versus “literature”. That’s the kind of effect I expected to trigger, and it did. Sadly a mod didn’t like it and wiped the whole thread. You can’t have subtle discussions on the internet, or even address that kind of racism. This is stupid. We HAVE TO talk about sensitive matters. Not simply ignore them like dust under a carpet. It’s EXTREMELY important to underline how prejudices we get toward “genre” are the exact prejudices that (many) “genre” readers have toward other stuff.

WE ARE NO DIFFERENT. We are no better. We just exchange one set of prejudices for another. We just belong to a different tribe, not a better one.

Anyway, this was my conciliatory post where I was tying back it all to the discussion of “genre” Vs “literature”:

—

Out of prejudices and expected canons, there’s surely a kind of dangerous line.

Most of these products are indeed filled with tropes, and they are targeted to very specific “genres”. There are hundreds of technical terms defining every possible variation, classifications of plots and characters. The “taxonomy” of these Japanese products would be alone an extremely fascinating topic to analyze. It’s like a whole sub-culture.

That said, you also can’t find anywhere else a similar amount of creativity and mixing of elements. There’s absolutely NO medium I know in western culture that comes close to the broad range you can find in anime (and by extension mangas, VNs, LNs). So that’s the dangerous line. It’s all filled to the brim with tropes and the rich taxonomy, but it also contains so many different elements that it surpasses every other medium.

So if you measure it all by quantity over quality, sure, it’s an ocean that is very hard to navigate. But it still has that fresh, wild creativity that makes it a very powerful medium. Targeting with very little prejudices, constrictions or filters the largest audience possible.

I was coming from one of the latest post on Bakker’s blog where he goes again with the debate about “genre” Vs “literature”: http://rsbakker.wordpress.com/2013/07/04/russell-smith-shrugged/

The bottom line is that genre readers have the tendency to be more eclectic with their reads, and coming from all sort of backgrounds (whereas “literature” secluded itself into predictability, rehash and complacency, getting dusty in their tightly compartmentalized world).

I simply generalized: a medium that closes itself (from the general public, also) becomes stale and can’t say anymore something relevant. It just rises its walls of canon and dies there. And that’s why I see the Japanese “young” market as extremely interesting. Its diversity is unrivaled if you pay attention at the whole range, and all its elements boil together in a huge pot, and so it all gets constantly mixed. A very good and innovative product can have a huge influence and produces an endless list of clones for many years, but the market is always ready for something that sets new trends again.

I’m just being coherent because I see how prejudices against “genre” aren’t that different from prejudices (or even simple difficulties at “getting” these strange products) thrown toward the eastern market of anime/manga/light novels/visual novels.

I personally come with no prejudices and do my best trying to “get” different things and markets. If I fail I blame myself, more than calling “shit” something I’m not getting. It doesn’t mean the stuff I linked here is “quality” and deserves your attention. At all. Most of everything is always mediocre regardless of what you’re looking at, and this is still a very commercial genre with an extremely broad (low? young? unpretentious? uneducated?) target, conceived for entertainment.

While the specific series in the image above looks at least like an interesting “mess”, I haven’t personally read it. So I can’t comment on its merits or lack thereof (though it looks dealing more with fancy battles than fancy boobs, as the covers would make you believe). I’m just pointing at an interesting medium because of how it’s built and how broad its public is.