The first lines of a post over at Bakker’s blog seem almost unreadable, but at the same time offer a very effective summary of his “Blind Brain Theory” (BBT) and especially why it’s important. It also ties together a number of aspects and brings out the true core of the issue. So I’ll try to give my own exemplification of all this, hoping that I can grasp this transitory moment of clarity (I always feel like I’m ironing. The moment I think I’ve smoothed out a corner, everything else gets wrinkled up again. My mind just isn’t big enough to encompass the whole thing. The blog helps nailing down some issues in a less volatile way.)

The satisfaction here for me is about taking something that sounds incredibly complicated and unexplainable, and unwind it so that it becomes smooth and planar. As when you’ve reached the top of the mountain and finally look down on it:

There are no representations, only recapitulations of environmental structure adapted to various functions. On BBT, ‘representation’ is an artifact of medial neglect, the fact that the brain, as a part of the environment, cannot include itself in its environmental models. All the medial complexities responsible for cognition are occluded, and therefore must be metacognized in low-dimensional effective as opposed to high-dimensional accurate terms. Recapitulations thus seem to hang in a noncausal void yet nevertheless remain systematically related to external environments.

Now let’s smooth this into something that makes sense, I think I can manage to make all this understandable even for non-specialists. “There are no representations”, this is already a very important idea. If you look at this video with Dennett, minute 2:35 and onward (but not for too long), he basically says that in order to think we need language. That’s what can distinguish human beings from animals, the fact that human beings have language, and so can reflect on things. To be able to “think”, Dennett says, we need to have an independent representation system.

What is this “representation(s)” that Bakker refers to? It’s simply a “model of reality”. We know that we don’t have a direct, unfiltered (or “analog” to use a technical term) perception of reality. We only have our five senses, and these five senses transmit information to the brain, information that obviously represents only a small part of total reality. Our brain then takes this information and tries to “organize” it into something that makes sense. So basically through senses the brain receives information, and then organizes this information into a model of reality, a sort of contained simulation. We know that the image itself, the perception of depth, color and so on, are all things that pertain to the model the brain builds. As conscious beings, we feel like we exist in the middle of this simulated reality, built by our brain by using the information it receives through the five senses.

This process I’ve just explained, gives origin to the fundamental idea we deal with here: a dichotomy or duality. There’s reality out there, and there’s the model of reality built by the brain within which consciousness dwells. We can call this organized model of reality “representation”, and it’s also defined in other various ways, like “Cartesian dualism”, or Cartesian theater, or model of the Homunculus. These are synonymous. They all refer to a duplicity between reality and perception. The “Homunculus” is the idea of imagining a “little man” within our brain looking at a screen. On this screen (the “theater”) our brain projects its model of reality, that little man represents our own consciousness. This is also the established religious idea (as well the main scientific one until recently): the fact that we are “more” than just physical matter, that we have a “soul”. And it’s again this duality that makes possible the idea we have “free will”, the possibility through out thoughts to decide and be free. All this is possible only as long we believe in this dualism, a distinction between the physical and the metaphysical. Free will, formally, requires independence from the environment, authority over it, so that we have that control and freedom. A “leap of faith” dividing physical matter and spirituality. You’ll see later what this space, this gap, actually represents. For now just remember I’ve mentioned it as the dividing space between the fundamental dualism (and I should also mention here “the God of the gaps”).

If these days we go watch 3D movies it’s thanks to the model I’ve just described. We can create the illusion of the three-dimensional image because we know the way our brain organizes visual information and so we can feed it information that has been manipulated to appear that way. Ideally this manipulation could be done in two different moments. It could be done, given enough technology, right at the level of the brain, making it organize it the way we want, or at the external level, of the information the eye receives, as we are doing with 3D movies. So this is possible because we give the eyes, and the brain, pre-organized and manipulated visual information. And since we only perceive our model of reality, instead of reality itself, we simply “believe” the representational model that our brain builds for us. But then all cinema works like that, since the illusion of movement also relies on a similar pattern. This simply to say that the Cartesian Dualism isn’t some fancy idea, but it describes the basic belief all of us share and that is ingrained in our culture.

Technically this dichotomy or dualism is defined in a branch of information theory as the “system/environment” distinction. It refers to the same stuff: the “system” building a model of reality, and the environment from which it takes information. This can be found even in popular culture, for example I watched recently episode 16 of Evangelion, an anime, and this is a dialogue from it:

– People have another self within themselves.

– The self is always composed of two people. The self which is actually seen, and the self observing that.

That’s a decent explanation of system/environment, and the Laws of Form by Spencer-Brown. You can find a more complete explanation here. The idea is that every possible observation draws a distinction, between what you’re pointing to, and everything else. That’s why we say, for example, that we need to know “evil” if we want to know “good”, or be able to see “black”, if we want to see “white”. As with language, we perceive the world in “digital” terms, through distinction. An undivided space for us is unknowable. The more distinction, the more specialization, the more detail. Human beings are “digital” beings because we only perceive this separation, and can’t deal with “analog” continuities.

Going back to that last quote you can see how it creates a paradox: in order to perceive a “self” you need to be able to point to it. In order to make the observation, to observe, you need to make your “self” the object. Instead of the subject. You need being, at the same time, both subject and object. As a cat trying to outrun itself to catch its own tail (imagine how it would look like). So you essentially need to build an ideal “double”, or mirror, of yourself. Once you have this double you can “know” it. There would be the observer “self”, and the observed “self”. Which means that in order to make reflection possible you need, in technical terms, to repeat the system/environment distinction. In the same way you (system) observe the world (environment), to know yourself you need to reproduce this distinction by making a system/environment distinction within the system itself. Observation needs subject/object. And in order to self-reflect, you need that the subject makes itself object, so he can observe himself.

As you probably can see the result here is one of “infinite regression”. Mise en Abyme, the effect you get when you put one mirror in front of another. The infinite tunnel of reflections. As in the model of the Homunculus, a little man in your brain looking at the screen, who within his little head has another little man, looking at another screen. In repetition, all the way down INTO THE ABYSS. Are you scared? This is what is going on, right now, into your brain.

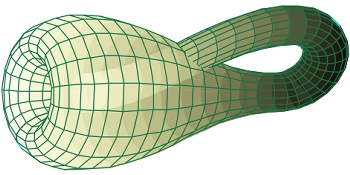

Self-reference, metacognition, present “patterns” that have been abstracted and formalized in Gödel’s incompleteness theorems. But it is a common, almost practical problem. How can you build a formal system if you don’t have an external one on which to rely? Gödel simply explained that even in math a fundamental rule needs to be supported by a more fundamental one. An origin is not possible, you always need something that comes before, and when you have it you need what comes before it. Infinite regression. How can a theory that regulates something also regulate itself if not through another theory, that will also need another definition? It’s as if to hang a painting we need a wall, and then the wall also need to be on top of something, and that something also needs some other sort of support. How is it possible that we don’t all fall down? Cosmologist have the same problem: if the universe is what began with the Big Bang, is there a bigger universe that contained the universe we are in? And that universe is then contained within a larger one? How many iterations? What’s “beyond” all this? The thing is, the paradox of infinite regression contained in our small brain is what we see all around us. The Hermetic mantra “As above, so Below”, or microcosm/macrocosm. In order to see and know something we need to distinguish between it and everything else. So if the universe is “this”, what is that lies beyond it? There’s a mathematical model called the “Klein bottle” that offers an “impossible” image that could help visualize the paradox. The Klein bottle is essentially a one-dimensional (non orientable) space, without an “outside”, and so the “one and boundless” space representing human consciousness, the qualia. And if you think about it, a one-dimensional space solves the contradiction of the distinction system/environment because there’s no inside/outside:

So there are these circular patterns, “strange loops”. The “environment” to observe itself needed to “knot up” into a “system”. Human beings serve as “observers” of the environment, for the environment. We ARE environment. A knotted chunk, become observer. Even widely respected men of science like Stephen Hawking fully embrace this perspective. I could use another popular (and genius-level) anime here, “The Melancholy of Haruhi Suzumiya” that essentially says what Stephen Hawking says at the end of that video:

“How about I observe. Therefore the universe is. Therefore, we can say if the human beings who observe the universe hadn’t actually evolved as far as they did, then there wouldn’t be any observations and the universe wouldn’t have anyone to acknowledge its existence. So it wouldn’t really matter if the universe existed or not. The universe is because human beings know it is.”

— Itsuki Koizumi

Or if you want a more scientific discourse, the Anthropic principle. An observing system, or a human being, is merely a peculiar knot of “environment”, that “looped itself” in this strange way, and became able to “observe” the rest of the environment. Environment becoming “conscious”. In order to “see”, it needed its own separate dominion, so that it could separate itself from the environment, becoming “system”. Thus the original dichotomy. And then, in order to not see just the environment, but also itself as system, it needed reproduce the system/environment distinction within itself. And so on, iterating the same distinction over and over.

These circular iterations, or “strange loops” are the main topic of a famous book that won the Pulitzer, “Gödel, Escher, Bach”. So that’s what you can have fun reading if you want to explore more the nature of these loops, which are the “key to consciousness”. At least in the way consciousness appears.

Because instead here what we want to deal with is not simply how consciousness appears, but how it truly is. And that’s what brings back to Bakker and his BBT theory. That’s why those lines I quoted at the beginning enclose the fundamental question humanity has been asking for two thousands years or more, and give this question a possible answer. That’s what BBT is. A possible answer to the most fundamental question. As Bakker says, a theory is just a theory and it needs to be tested to be proved true or false (or truer or falser than whatever current model we hold), but as it is right now it is at least a proposition that seems able to do what it sets out to do. And it is both elegant and parsimonious, which means that it solves in simple ways a huge number of complicate problems, that then is usually a good hint pointing in the right direction (like Occam’s razor principle).

What is BBT’s answer then? What BBT tries to do is FLATTENING the bi-dimensionality (system/environment, consciousness/natural world, metaphysics/physics) into mono-dimensionality (just environment, just natural world). Or solving what is normally called the “hard problem of consciousness”.

Bakker believes that human introspection is intrinsically tragic. It can only trip itself over and over. Make a clown of itself. That’s why he has no faith in philosophy. It can only be revealed as a most tragic failure. He believes that “consciousness” is a cognitive illusion. So if you were able to turn things inside out, and so describe consciousness NOT as it appears to us from the inside (Plato’s cave) BUT from the outside, then this different model would “explain consciousness away”. Basically it would elegantly do without the need of any “consciousness” or “dualism”. If you were to revert the perspective the cognitive conundrum would be solved, the illusion of consciousness would be cleared.

Bakker subtitled BBT as “the last magic show”. It’s really a nice example because the basic form of “magic” (as we know it) is about the removal of information. You can’t see how the coin changed hands because your eyes didn’t see the movement. The magician “subtracted information” from your perception, and so you saw “magic”. Something impossible because you couldn’t see that link of information, you only saw the impossible leap, and your brain didn’t manage to fill it, if not with “magic”. All this is easily and linearly explained when applied to “consciousness”. Human brain is the result of very slow evolution. At the beginning the brain’s purpose was to navigate the environment in a efficient and efficacious way. So all its “tools” were built to that purpose: model the environment and deal with it. But only very recently the brain developed “introspection”, which is essentially the brain turning to itself in order to model itself too. Bakker says that our “introspective tools”, that he calls “heuristics”, simply weren’t built to effectively be able to model the way the brain itself works, they were built for the environment. And so we ended up with some blunt, clumsy tools that simply created a number of illusory and wrong perceptions. Being these tools extremely unsuitable for self-reflection, we only obtained “cartoons”, or caricatures of the truth.

Philosophy is a complete tragedy because it ends up sharpening the bluntness itself. It’s the superlative, the apex, the exponential maximum of human thought. And so of the human error. Instead of leading us to “truth”, it perpetrates the ILLUSION. Monumental cathedrals of thought, immense, illusory, self-contained constructions. Illusions of autonomy. Self-reliance. Monuments of stupidity. Testifying our very flaws and tragedies. Only the desperation you achieve by using these Broken Tools.

Since the tools we use to model cognition, these heuristic, are so unsuitable and low-resolution, we end up with these caricatures, or cartoons. Just horribly vague approximations that do not even come close to “truth”. Where there’s a “knot” of environment, we just see undefined space. We don’t have enough detail to go there, and so this knot appears unsolvable. Unexplainable qualia. A Feeling. A vague something we just can’t pinpoint. And so we rely on the cartoon we have even if it’s only incidentally linked to the truth.

Simplifying, think to three abstract points, A, B, C. In truth, it’s B that actually links A to C (as in the magic show B represents the subtracted information). But if we are constitutionally blind to B, then in our perceived world we see A directly linked to C. We are CONVINCED of the A to C relationship. Think to superstition in sport and how actually widespread it is. The obsessive compulsive behaviors, if you have done certain things and you end up winning the match, then the next time you feel compelled to repeat them, regardless of what your rationality tells you. Wear the same colors, the same sockets, or all sort of ridiculous habits like sitting always north at a table. This merely because we are subject to our cartoons and simplifications. We tend to accept a relationship between things even if it doesn’t make a lot of sense. We make caricatures out of everything and we actually rely on these caricatures to govern our lives. We act irrationally more often than we act rationally, and this because we lose track very soon of what is what. Too much hassle. When we see a correspondence we embrace it. It’s cartoons all the way down. Poorly organized, inefficient cognitive conundrums.

Now that I explained the overall scheme I return to the original quote. “There are no representations, only recapitulations of environmental structure adapted to various functions.” I explained that “representation” is the model of reality that the brain organizes. For Bakker this is the illusion. What we THINK we see. He says that there’s no duplicity or duplication. No duality. No theaters, no projections and no Homunculus looking at them. There are only the various cogs of our brain, specialized for specific functions. This all in unconscious space, or outside of conscious perception as we have it.

On BBT, ‘representation’ is an artifact of medial neglect. Medial neglect is essentially the unperceived “B” in the example above in the A->C relationship. So he says that what we consider “representation”, the model of reality, is the illusory appearance of a relationship, that we can’t accurately know because we lack the information to be able to. We lack information, detail. So it’s like a blurry picture, the cartoon. The tragic simplification. The superstitious belief of correspondence between the color of socks and a sport match being won. Wild inaccuracies. the fact that the brain, as a part of the environment, cannot include itself in its environmental models. The “fact” here is that evolution didn’t give us good tools for the brain to map itself correctly. So we ended up with a “spandrel”, a bad result of trial and error.

All the medial complexities responsible for cognition are occluded. This should be straightforward. He says that what we need in order to obtain an accurate picture is “occluded”. Or better: we miss access to most of the cogs in our brain, and so what we have isn’t remotely enough even for an acceptable approximation of truth. and therefore must be metacognized in low-dimensional effective as opposed to high-dimensional accurate terms. Low-dimensional means inaccurate. So sketches, cartoons. Vague blobs. And also correlations between stuff that isn’t directly correlated. Incidental correspondences.

Recapitulations thus seem to hang in a noncausal void yet nevertheless remain systematically related to external environments. And that’s it, the qualia. The “recapitulations” are the name Bakker gives to what we perceive as “representation”. The idea is that this model of reality as we see it “seems to hang in a noncausal void”. This represents the origin of the duality, the way we think consciousness as separated from the world, existing in its own metaphysical dimension: the noncausal void. The soul. Hanging there, somewhere. The breath of life. A wind with no origin. It’s suspended in a void because as explained above all the links that tie it to the ground, or reality, are unperceived. Medial neglect. A skyhook. We don’t have the tools to track those links, and so we end up with a picture that isn’t hung to a wall of reality, but just “floats there”, magically.

This is pretty much it. Despite the lengthy explanation my hope is that it seems quite linear. The basic story in the end is simple. The brain was originally meant to deal in a efficient and parsimonious way with the “environment”. Then only very recently in the breadth of evolution the brain started turning on itself. Trying to track not only the environment but also itself. And to do this it was only able to rely on the same tools that it developed for the other purpose. And so required, as it modeled the environment, to put itself in this model too so that it could observe itself (reflection, metacognition, introspection). Hence the “double”, the Cartesian Dualism, and all the consequent problems with consciousness, the soul, God and all other metaphysical ideas. Tangled in the cognitive conundrum, the labyrinth of the soul, trapped with the minotaur and unable to get out.

Daedalus had so cunningly made the Labyrinth that he could barely escape it after he built it.

I’m enjoying the labyrinth. So I hope I’ll stay trapped as long as possible.

A follow up to the previous post. Despite the latest (3rd) reboot movie isn’t getting the best feedback from the public, at least there does not seem to be suspicions of a compromised work because of who worked on it. It happens that with popular franchises the original creators move on, and so they lose that kind of original intent and creativity. They become a commercial endeavor. But in the case of Evangelion Hideaki Anno and most of the original staff have always been at the helm, and are still there doing these reboots. So if they ruin it, at least they have the right to (and hopefully a good motivation too, these aren’t guys that do things lightheartedly and without passion).

A follow up to the previous post. Despite the latest (3rd) reboot movie isn’t getting the best feedback from the public, at least there does not seem to be suspicions of a compromised work because of who worked on it. It happens that with popular franchises the original creators move on, and so they lose that kind of original intent and creativity. They become a commercial endeavor. But in the case of Evangelion Hideaki Anno and most of the original staff have always been at the helm, and are still there doing these reboots. So if they ruin it, at least they have the right to (and hopefully a good motivation too, these aren’t guys that do things lightheartedly and without passion). These days Evangelion is once again getting some attention since the third movie of the reboot recently came out in Japan in BD format, and fansubbers are hard at work on it (and fansubbers also usually do a better work than official releases, since a work of love is usually better than work done for money).

These days Evangelion is once again getting some attention since the third movie of the reboot recently came out in Japan in BD format, and fansubbers are hard at work on it (and fansubbers also usually do a better work than official releases, since a work of love is usually better than work done for money).