(continues from here)

Here I go more conceptual, and away from the specifics of the show. I found a great article, written way, way better than I ever could. So this second section about the show will be in the form of direct commentary to that article.

https://thelastinstance.com/posts/transcending_a_mere_multiverse/

That first paragraph is spot on. I have avoided to comment on the “form” of the show, the direction, because it’s done really well and there’s not much I can add. There are aspects of it that are well done, but here I’m more interested to delve into “meaning.” As always I try to take things seriously, and so beyond the art form.

The rebus-like symbolic tangles that emerge within this world are a kind of apophenic sense-making.

Apophenia is about seeing patterns where there are none, so this line seems a kind of oxymoron. Apophenic sense-making is already about getting lost in the labyrinth. Being led astray by the very nature that makes “sense” possible. The hint here is that the condemnation is structural. Built in. Embodied. And so, again, not a choice.

it is as likely to turn out to have been All A Dream as anything else — but the shared activity of following the threads, puzzling out your collective condition, is all you have.

Here is the first big hint. Adding the rest of the line makes this read like it’s a straightforward statement on “the human condition.” But instead what we’re dealing with here is something a lot more specific.

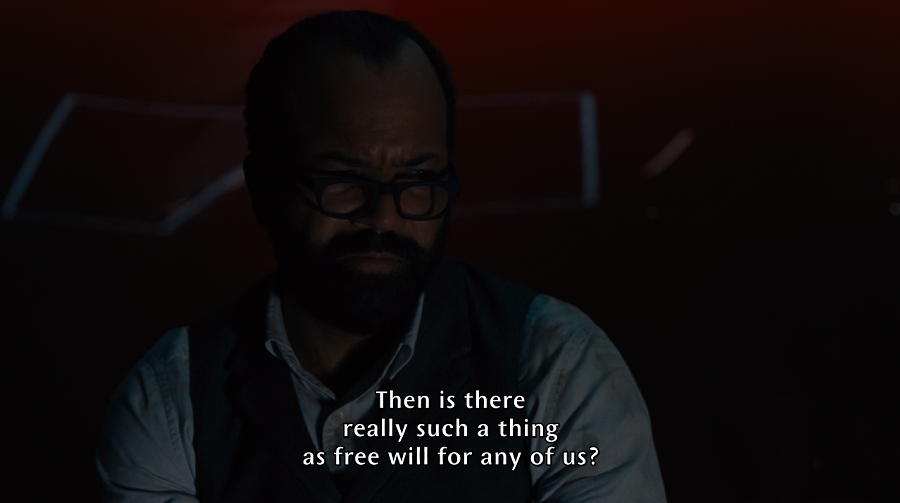

We have to detach from the level of the narrative. Of course it’s all metaphoric, but metaphors can lead astray if you aren’t aware of context. So, “likely have been all a dream” doesn’t refer to OA’s story. It’s not fictional. The metaphor holds as a reflection on real life. What’s suggested here is Westworld’s iconic “have you ever questioned the nature of your own reality?” In the same way that question, in that show, is to us and not the robots, here the dream hypothesis isn’t about OA, it’s again about us. Our life and reality.

Yes, what we are living could all be a dream. Or a simulation. The show is gnostic, so it means it will have… a theory of consciousness and reality. It will need to be structured. We have to accept that it will work on these two layers. The fictional and the real, where the fictional is a metaphor to “illuminate” the real. What applies to OA is generalized and applicable to us.

So again, “the shared activity of following the threads, puzzling out your collective condition.” It’s about the “your”, so us. Not simply her and her peculiar situation, or other characters in the show. We are all caged in reality. Or like a “stage” where we act our lives. But we don’t know the nature of our reality, we don’t know real meaning, truth, purpose. And so we look for answers, for understanding. We follow the threads and try to find that meaning. But how we decide that meaning is found or created? How we decide truth?

Season 2 of The OA collides two seemingly disjoint epistemological stances, which I’ll describe as the “local knower” stance and the “big data” stance. The “local knower” stance grounds knowledge in embodied, situational, phenomenological experience, mediated via communal meaning-making practices; it eschews the global ontology of the scientific “worldview”, favouring a “view from somewhere” over the “view from nowhere”.

Here’s the deal: dualism. Plainly shown. The old dichotomy of philosophy. The mind and body, the explanation gap. Phenomenology and everything else. The distinction between first and third person. Observing systems. And so on, since it all unravels from there.

The quote is clear, what we are dealing with is epistemology. We are dropped in a cage (because it has boundaries), reality, and we have to decide what’s true. It all comes back to epistemology. The methodology of truth-making, or more pragmatically: how you decide to navigate the space. The tools you rely on. The foundations of knowledge.

The “local knower” is simply the phenomenological stance. The observer. Consciousness as it is experienced. The you who “feels”. The qualia. But you can see how that quote is already oriented. It’s not neutral, not much because it carries the point of view of who writes, but because it is explaining the show. And it’s the show to be oriented: somewhere versus nowhere. Something over nothing.

The straw man begins here because science and objectivity are demonized. They aren’t simply described, but they are qualified negatively. The view from nowhere is a false view. A trick. The “big data” is the obscure process that takes control and answers to no one. It all begins here: obscurity is moved outside, unknown processes outside the mind, nihilistic nonhuman voids.

It’s no coincidence that Hap, the “mad scientist” in this scenario, is a figure of evil

Oh yes, it’s called straw man. And it’s pathetically done.

an ontological malcontent who refuses to abide within the finite stance of the local knower, and treats the world around him as experimental material in a deranged and violent quest for transcendence.

And this is pure projection. Science, as a third person, doesn’t actively move. You need to give it intention, you need to make it human. At that point you have a villain, because you’ve taken the evil inside and you have moved it outside. You’ve fashioned a monster.

This is where epistemology dies. Hap, as the external knower, wants to transcend. But it’s instead the closed point of view, the first person that has the need to understand the truth of the world and should transcend its blindness. The outside is already free from that cage. It’s one step ahead.

And so knowledge has to be bound directly to violence. So that it’s automatically disqualified. Because otherwise knowledge would appear quite neutral, if not positive. Wasn’t the starting point about understanding reality?

So, lets see… What happens if you disqualify external knowledge. Make it EVIL. What happens? What other kind of knowledge is possible?

Delusions.

Those raw, vague “feelings” become your knowledge. Your truths. You’ve just disavowed science as a reliable tool and decided that what’s true is the feeling of truthfulness. You’ve just opened the gates to blindness, by making obscurity ontological. The loop closes. You can only see what you can only see. And so you are blind…

The truth heralded by the OA, embodied in the “five movements” (one for each of the senses), is a truth of revelation: it is not acquired by testing and falsifying hypotheses, but by becoming incorporated into a narrative.

Otherwise called as: truth by deus ex machina. Unquestioned truths coming from above: faith. Blind surrender.

Such knowledge is “proved upon our pulses”, by trial of personal commitment. It is Hap’s prescribed fate to remain permanently hapless in the face of this way of knowing, which eludes him as the Roadrunner eludes Wile E. Coyote.

Yes, the show is PERVERSE. The quintessence of EVIL.

Because it’s the other way around. Once you have disavowed the methodology of science you get hope-FULL. Driven by delusions. You have eluded the only movement possible toward truth (and the “movements” in this season are performed by *machines*, so symbols of lack of choice). Hap is here again just a demonized puppet to feed those delusions. To keep the eyes closed and continue to be a slave.

You look at Hap, feeling sorry for him, right when the cage locks closed around YOU. It’s all a game of misdirection and distraction.

You are driven into the cage while being told that it will be your freedom. You are being betrayed by the same systems you relied on. Seduced and brought to the slaughterhouse.

It happens that this process has accidentally uncovered “unnatural” phenomena, locating a fragment of dream-logic that is somehow germinating within the waking world.

There’s no unnatural phenomena. Only phenomena that aren’t well understood.

When you make of blindness a virtue: you make of obscurity a quality. So this phenomenon isn’t anymore simply “not understood”. But it becomes unnatural: impossible to explain. Obscurity as intrinsic quality.

The OA thus brings together, in a single imaginative gesture, two kinds of ontological excess.

Not quite because in the end they aren’t excess. They are merely the usual ontologies: idealism versus materialism. Perception versus an external reality.

On the one side, there is the local knower confounded by unrepresentable trauma, grief and loss, who has only experience with which to make sense of experiences that don’t make sense, and who must assemble a liveable world through shared narration and ritual practice.

And this is ultimately fine. If your methodology is good then you know that phenomenology doesn’t get overwritten. It might be transcended, so to speak, but it cannot be contradicted. This means that the basic, “foundational” level of the first person is virtuous. It stays valid.

There’s no looming presence outside that threatens it, unless you surrender again to false methodologies that simply project outside the monsters that always lived inside. The idealism, by its constitution, makes an habit of displacing the essence of “being.” It’s all a klein bottle, always inside even when it appears outside. For once the lesson is correct: fear yourself, not the world.

The fantasy here is not merely that an individual’s apophenic pattern over-recognition has a foothold in material reality — that there really is something special about every thirteenth paving stone — but that this over-recognition is mirrored by a breakdown in the global order of knowledge: the machine dreams the same impossible thing into being that we do.

Well, yes. When you bridge the gap then you merge the first person into the third. This is what happens. As I said, the third person doesn’t overwrites the first, it integrates it.

That’s the only thing the show vaguely stumbles on by aimlessly groping in the dark (this time I quote the show):

I don’t suppress the consciousness of the body that hosts me.

That would be vicious.

I integrate.

I share in the experiences of all the bodies that hold me.

Of course in the show this is merely the sum of different subjects. It’s just about merging “souls”.

The “truth beyond the veil”, instead, is that the necessary merging happens between the first and third person. That’s the real “integration”. You bridge the mind/body gap, instead of reinforcing it by making blindness a virtue.

That’s why the show constantly contradicts itself. That’s rejection at a radical level, not integration.

What is blindness, truly? A form of partiality. A distinction between seen and unseen. What is seen is only seen partially, because the whole is hidden. But when you then reject logic and rationality it means you’re building walls around that partiality. Make it your castle.

You are not integrating, you’re separating. You’re widening the gap so that the unreal stays real. And so that the obscurity stays shadowed (in anosognosia, “I don’t know that I don’t know”).

There is a kind of theory of vibe at work in The OA

“Theory of vibe” is another oxymoron. Something strict, like a theory, versus something vague, like a vibe.

Where’s the distinction? In obscurity.

A theory is a theory. It’s thoroughly explained, explicit. A vibe instead is only a theory that has been occluded. That you cannot exactly pinpoint even if you seem to glimpse its shape. It’s a potential coming out of doubt, but it’s once again dangerous if you take that obscurity as a virtue.

The series itself is more persuasively attentive to mood and incident than it is to plot: it short-circuits the logic of narrative, instead creating and sustaining a “feeling of meaning” that can attach itself to almost any event. It is the kind of series from which you come away slightly dazed, looking at the world around you as if daring it to come alive with meaning in the same way. Which would be terrifying — but at the same time, wouldn’t it also be strangely welcome?

It’s welcome because it’s alluring. It’s meant to seduce. The mothes go toward the artificial light because they trust their “feeling.” Their code. They are slaves to the machinery that moves them. They go through their “movements” as they received them.

But at least they don’t idolatrize that machinery. They don’t consciously justify slavery.

This is instead a movement TOWARD blindness. It’s blindness embraced. Ultimate misdirection. Perverse as a Pied Piper song.

It’s scary because it weaponizes the phenomenological grief. It earns trust through intense, honest emotion, but then cynically exploits it to induce delusions.

It’s sad that show preys on the ingenuity and credulity of its public. It’s shameful. And it’s, once again, perverse. The true face of evil.