This is a direct follow up to the previous.

I let some time pass because I didn’t want to get stuck writing, even if knowing this severely weakens intent and efficacy (and always consider this here isn’t a dialogue, but just a kind of soapbox where I mostly talk to myself to clarify things for my own use. That’s all. Whoever stumbles on here, they are on their own.). That previous post was written across several hours, and I edited a section later in a way that doesn’t make that much sense. I already intended to return to it.

I mentioned how a month earlier I had randomly stumbled onto another conversation where a Bakker fan couldn’t see anything of value within Erikson’s work. In that case it wasn’t someone arguing in bad faith, and turns out it was one of the old guard on ASOIAF forums. That opinion isn’t especially surprising for me. GRRM’s forum had at the time an ongoing thread dedicated to Bakker, and it made sense for the way Bakker’s series is written and the attention to detail of its worldbuilding to be somewhat closer to GRRM work. In the style of prose, point of view, and structure. It’s somewhat more canonical. And I can understand that Erikson’s work, instead, can be seen as more juvenile and shallow. That’s why I suggest “Forge of Darkness” as an inverse point of view on Erikson’s work. It’s not that “Gardens of the Moon” starts in a way, and then the series takes a sharp turn toward the introspective. The books aren’t at odds with each other. But I understand it’s very easy to miss what in the first book is merely a hidden undercurrent and that later becomes a lot more prominent. You can find the same flavor in that first book, but you need to know where to look. As a first read you’ll most likely miss it entirely. That’s why it takes SEVERAL books to “get” Malazan. It’s something that has always been there, but only slowly comes into focus. You want a book that has that core in focus from page 1 and is unrelenting in its quality? Then Forge of Darkness is precisely that. Then you go back to the main series and you can see how that newfound perspective continues to be valid for all the books in the main series. But you need that sort of “backward” perspective to find value in Malazan. Something that Bakker’s work doesn’t suffer in any way. If anything, it’s a forward perspective, since a lot of what is in the first book informs meaningfully what comes after.

(btw, Werthead, who’s one of the old guard supporters of GRRM, also says this: “His worldbuilding is solid, better than most, but also is full of holes that even people who like the series will poke at out of amusement.” Along with the fact that a lot of the worldbuilding choices were made merely because they seemed “cool.” Only later, as the series developed and the fans started to show a dedication to the tiniest detail, Martin also started to look more closely and take care, so that the world felt more and more like a real place. Even in this case, it was a process. Partially driven by the readers’ expectations and demands more than a pure and uncompromising vision from the very beginning. These projects grow into their own maturity. Bakker being the exception because he’s fully committed from the first page you can read, and never yields.)

But this was a moment of surprises, so I’ll mention this other video I randomly stumbled on. That again defied my own expectations of what I consider plausible. It’s an harmless book tier video from someone who read the whole Malazan series. He ranks most of the later books at the bottom of his tier list. This is not really weird, everyone comments how the books do become slower and heavily introspective in a way that for a lot of readers is too cumbersome. But he also ranks the first book close to the very top. The interesting part is his motivations, and as you can listen in the video, this is a reader who loves the plot. I could say the more shallow layer, that is indeed more prominent in book one and three. Again, nothing surprising because book 3 has always been considered a fan favorite in general. But I just didn’t think it possible that a reader could simply appreciate that one layer in almost total isolation and still feel the whole series worthwhile. I guess these books are so crammed with ideas that even when you embrace a small portion of the whole, for some readers it’s still plenty enough.

For me it still feels unlikely that you can digest Malazan without being “in there.” It’s almost political. I think the books will eventually reject the reader, if the reader denies those forms of empathy and sensibility that the books force. You have to be there, tuned to that type of vision, of the world, of humanity. You can’t glaze over, that’s what the books actively oppose. You can’t brush it off. It makes sense that you see none of it in the first book, and then the second or the third you still get distracted by the more spectacular and louder parts. But eventually the voice demands something of you. You’re either in or out.

It’s not possible to mistake what you’re reading. It’s a filter.

And yet it fails. Spectacularly so.

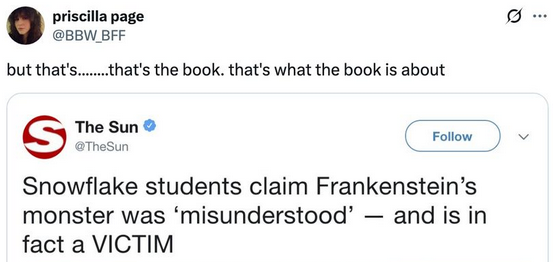

That first post I pasted as an image, “dissing” Bakker, came from a fan of Erikson. Not just one random fan, but someone who cared enough to run a podcast. And I just can’t understand HOW. How can a work that so explicitly demands for empathy, then completely denies it. How is this not an impossible, implausible contradiction?

Again, I can see someone appreciating Bakker not getting Erikson, because of how it’s written, because of its many “distractions”. But the reverse is downright absurd.

Then we get to the third case, again in the previous post, but I don’t see any worthwhile pattern there and I simply won’t believe it wasn’t arguing in bad faith. What’s curious is that it came from an hardcore GRRM fan. And so our table is set up. We have GRRM fans who hate Bakker, whose fans hate Erikson, whose fans hate Bakker. And whatever other combination you come up with.

Look outside and see a world on fire, filled with hate. And then even our curated “fantasy landscape” is just a mirror. How is this possible? What happened to that filter? What happened to the “power” of fiction? I only see failures here. Writers who spend their life trying to communicate something. And it fails, again and again. Bakker’s searing eloquence, reduced to nothing. Erikson’s pleas, crumbling as rhetoric.

How can you make sense of all of this?

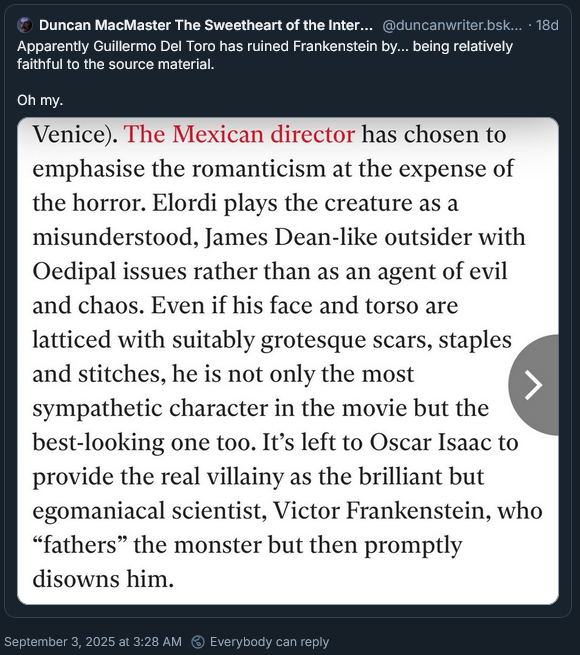

Bakker’s books then become pro-fascism.

Mistaking description for prescription.

Apparently, no, literature won’t save us.

I don’t even usually browse reddit, only randomly stumbled on those two single threads for completely different reasons. I guess it was bad luck.

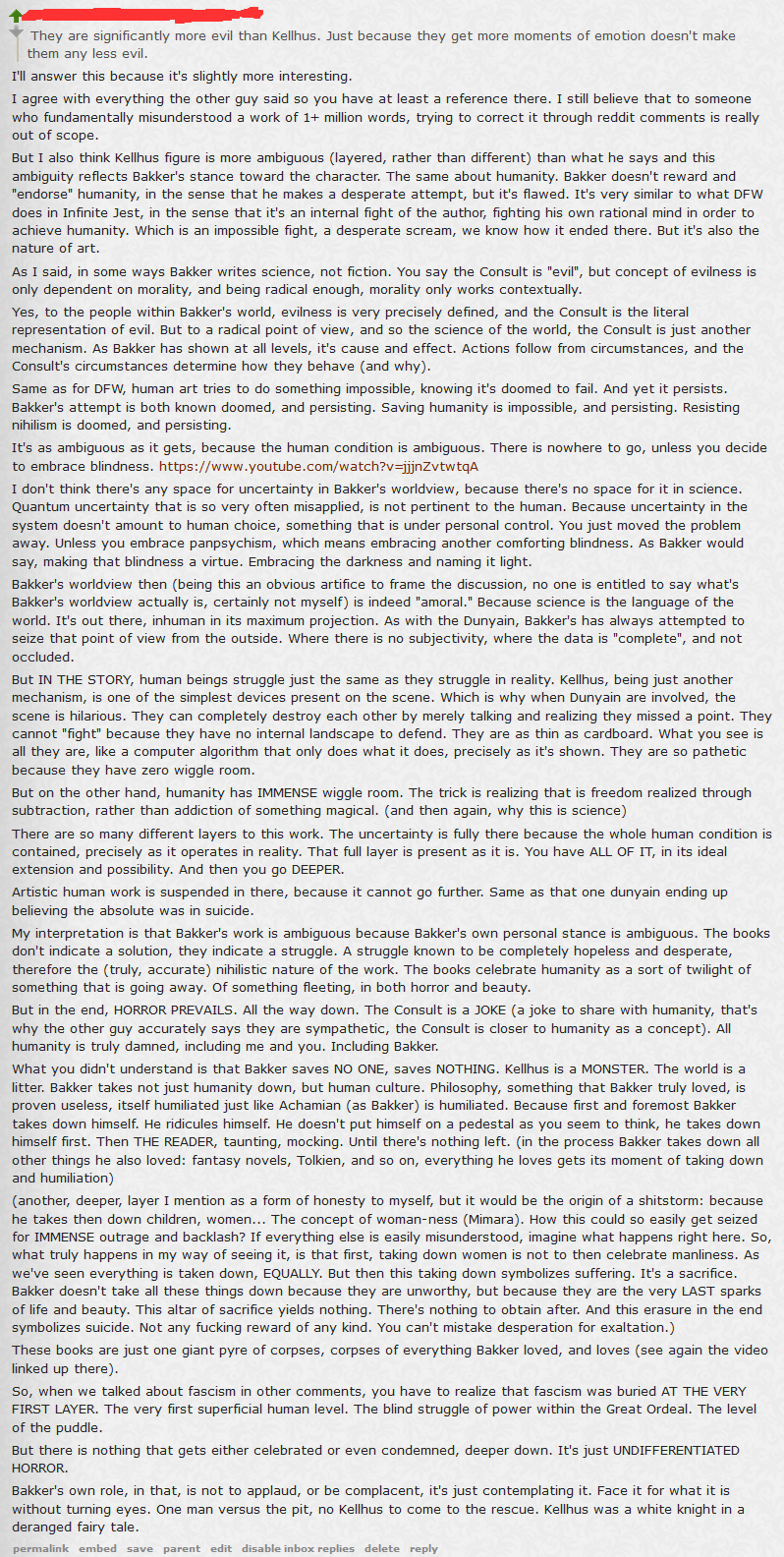

I’ll archive here one of my own replies, since I give more of my perspective on how I read Bakker:

For ease of clicking, this is the link in that post: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jjjnZvtwtqA

This one more rambly post is not to be taken as a sort of objective read of Bakker. It’s my own, more subjective interpretation. But even considering that, all I wrote comes directly from what’s written in the book and I always tried to stay away from more speculative thoughts.

One last point I wanted to clarify, and I think I already wrote about in the past. This is a quote from the other guy that was “defending” Bakker:

I still don’t quite agree with what Bakker was doing here. It is indeed what the books seem to say, but it’s not coherent.

“Madness, those parts of him without provenance”

This seem to imply some sort of magical nowhere. But again, it’s not coherent. Madness is merely an artifact of point of view. It’s a layer of interpretation, it’s not “the world.”

I can observe a man going mad, in the sense that his actions appear not being rational, they “don’t make sense.” But not knowing a cause doesn’t equal the fact that a cause does not exist. If some mental illness causes madness, then madness has a rational cause. On this level “madness” is precisely the layer of interpretation, assuming behaviors being always rational.

So actions and choices are interpreted as madness because they APPEAR not having cause. Yet they don’t escape the causal system. They merely escape knowledge of who’s observing: the causes are not evident, explicit. But they still exist within the system.

I still don’t quite understand what Bakker was intending to do, because it really looked like he tried to ascribe madness some kind of metaphysical efficacy. Rather than just another, plain, blind spot.

One Comment

Hi – returned to your blog on something entirely unrelated, checked the updates and saw that you mentioned our discussion from a few weeks ago. Just a slight correction, I don’t see Erikson’s work as without merit, in fact I did enjoy quite a lot of it even though aspects irritated me something fierce. I’ve contemplated diving back into the series in 2026 but the sheer length (and the huge stack of books already demanding my attention) is a constant deterrent. Well, maybe someday.