I became aware of Christopher Ruocchio around January 2024, about a year ago. I was starting to watch youtube videos that were suggested, rather than sticking to my own feed, and as it happens, once you watch one type of video the whole page fills with lookalikes. So I got also introduced to lots of the popular “booktubes”, or whatever they are called. Both the internal and external effects are like an avalanche: you get hit by constantly repeating patterns. For example in the last couple of months everyone seems to be reading and talking about Robin Hobb, which is both nice and weird, since so many readers are now jumping on a fairly older series. But why now? Yet the result of this type of avalanche is actually nice, because even in my case it stimulates interest in reading and sharing the same thing. Keep the ball rolling and enjoy the process.

I became aware of Christopher Ruocchio around January 2024, about a year ago. I was starting to watch youtube videos that were suggested, rather than sticking to my own feed, and as it happens, once you watch one type of video the whole page fills with lookalikes. So I got also introduced to lots of the popular “booktubes”, or whatever they are called. Both the internal and external effects are like an avalanche: you get hit by constantly repeating patterns. For example in the last couple of months everyone seems to be reading and talking about Robin Hobb, which is both nice and weird, since so many readers are now jumping on a fairly older series. But why now? Yet the result of this type of avalanche is actually nice, because even in my case it stimulates interest in reading and sharing the same thing. Keep the ball rolling and enjoy the process.

(no matter what you/I read, the moment the process of reading is confined to itself, it dries up and feels like time wasted. Instead when the process of reading is preceded by other times when I spend time reading about the book, or other books, about other people reading and sharing, so that the moment of actual reading is better connected to the rest, then the process flourishes, I do enjoy reading, more)

So it was the case of Ruocchio that suddenly seemed to appear in lots of favorite book lists. Maybe being the very beginning of (last) year triggered all sort of recaps, and those books ended up being mentioned a lot as favorites, stringed with superlatives. Somewhat weird for me because I had never heard of Ruocchio before, not even a single time. I haven’t been very much in touch, but in certain circles Ruocchio seemed to be completely absent, only to be a main topic in certain others. This triggered curiosity for me and so I kept delving. A similar process led me to discover Jenn Lyons, a while ago, that I still remember quite positively (I already got all five books, just need to decide when to read them), so I’m always happy to find spaces to explore that are completely new to me, despite still having tons to read in those spaces I already mapped. A certain leap of faith.

Problem is, delving more, reading reviews, hearing Ruocchio himself through lengthy interviews that were quite informative both about the nature of what he was writing, but also of the decaying state of the publishing industry…

While my appreciation of Ruocchio himself grew, my interest in the books waned. In the end I decided I could do without. Problem is, again, that the youtube-driven avalanche continued. The seed of that curiosity didn’t go completely away and so about a month later I decided that, yes, I was going to read Ruocchio. In fact I went from “I do not really care about this”, to “please, can we speed up shipping? I want the book right now.” These books are actually quite expensive despite being simple paperbacks, so that part added to the initial hesitation. They weren’t impulsive purchases (for book 2 & 3 I switched to the cheaper and smaller UK edition, I do not regret this at all). Funnily enough, at the same time I got curious about Modesitt‘s Recluce, and this new interest completely robbed the hype out of Ruocchio while the book itself was in transit. But! In Modesitt’s case getting my hands on a copy of “The Magic of Recluce” meant ordering an used copy from the US, and so WEEKS of wait for the delivery… Meaning that while my hype got sidetracked, it left the space for Ruocchio to land on my lap just in time (this doesn’t sound right, I’m sorry). And so I started to read, almost exactly a year ago.

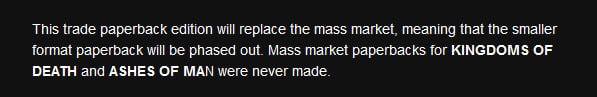

One of the reasons why I decided to read is about the structure of this whole thing. As with Jenn Lyons, I appreciate that these writers set out for an ambitious plan and then deliver. Ruocchio is a relatively young writer, he set out with an ambitious, multi-volumes space opera, and right about now he’s writing the last 50k words of the very final volume. The seventh. Some 1 million 800k words when complete. The original plan was to have two different blocks, two trilogies for a total of six books. But then DAW happened, or rather Astra’s hostile takeover (we won’t linger on that, as I’m trying to write a review and not an encyclopedia). After the third book was published, and even if the sales were improving (hello youtube), the publisher imposed Ruocchio that the fourth book wouldn’t exceed 200k words (the third was already 285k), and that the series would conclude with the fifth. Problem is Ruocchio already wrote 300k, as part of the fourth. The following wasn’t going to be any shorter, and then he had a SIXTH planned… This put him in an impossible to solve situation, because there wasn’t any amount of editing and cutting that could plausibly work. Right at this point he started to realize that the whole project could as well completely fail and end there. He didn’t have much to bargain with the corporate overlords (now I’m starting to sound melodramatic same as the meta-commentary of Hadrian in the book… Oh well.) So he decided for a temporary solution: he published the first 200k of what he wrote, as a fourth volume, then had left those spurious 100k at the end, and rather than trash them, he set out to write another 100k half-of-a-book, to glue in as an unplanned transition toward the second part already written. Go figure, this frankenstein procedure wasn’t fully successful and now the general consensus of reviews is to consider the fifth volume as the weakest in the series. This is an example of how we generally consider publishers and editors necessary to improve and polish the art, when in many cases they are obstacles (Michelle West is another of these cases, DAW strikes again). What happened next is that Ruocchio gave his publisher what the publisher asked, volumes 4 and 5 as close to perfect 200k words cuts, but certainly not the end of the series. He instead switched publisher, only to have DAW came back to him with their tail between their legs, because Ruocchio got popular and they really wanted to publish that last book, even if it exceeds 300k words. How things change when you show the money rather than the art…

Despite the incident with books 4 & 5, Ruocchio found a way through and now the series is set to achieve whatever goals were initially planned. There’s a well established consensus that book 1 to 3 are on a upward trend, with the third book being considered exceptionally good. That book 4 is bleak, that book 5 is weaker because of what already explained, and when Ruocchio started to write book 6 he decided that he would at least try doing his best to surpass the third book. He mentions this in interviews, of how he didn’t want to simply leave that third book as the apex of the series, giving a sense that everything following it could be omitted. The success of this goal was debatable (not by me, I’m merely here to write a review of the first, if I’ll ever get to the point and not get drown in this ever-growing premise), but I respect the lucidity of the goal. I respect the writer, the plan, I’m onboard. And at the time I was looking for space opera that was ambitiously “large.” Which is not something easy to find in sci-fi, outside of Peter Hamilton. Fast forward to the summer, I then moved to three completely different authors: Greg Egan, Peter Watts, and Alastair Reynolds. But this is a story for a different time.

I am a reader (and writer, apparently) of infinite prologues. I enjoy dwelling in the sidetracks. I enjoy the slow burns. As a premise, Ruocchio was doing the right things: he had an ambitious plan, he DELIVERED it with a wordcount to show, no matter if good or bad, there was a definite upward trend to look forward to. And it was the wide-ranging space opera I wanted to read about. These were the main movers for me, but I started reading as a VERY skeptical and jaded reader.

What is this book truly about, then? Well, it is all in the first page. Nope, not that first page of chapter 1 with that pompous beginning “Light. The light of that murdered sun” bla bla… I mean the page before (actually two). The “acknowledgments.” It’s that page that becomes a pompous introduction that indeed sets the tone for everything that would follow. Now that I’m done with the book I know that the initial intuition was correct. I read that whole, lengthy and rhetorical page, only to then turn to the first page of chapter one to read THE SAME THING AGAIN, but now… fictional.

If I were to list every family member to whom I owe some depth of gratitude, I would have to publish a genealogy, so here’s a short list: to Uncle John, for his help understanding contracts; to Brian, for reading the book before anyone else in the family; to Uncle Pete, for indulging my requests for artwork when I was little and for showing me it was possible to be an artist and a success in life; and to my mother’s mother, Deslan, who bought me my copy of The Lord of the Rings, which along with Star Wars made me want to tell these stories. And to everyone else, for being truly the best family—and a better family than I truly deserve.

I had all the education you might expect the son of a prefectural archon to have. My father’s castellan, Sir Felix Martyn, taught me to fight with sword, shield-belt, and handgun. He taught me to fire a lance and trained my body away from indolence. From Helene, the castle’s chamberlain, I learned decorum: the intricacies of the bow and the handshake and of formal address. I learned to dance, to ride a horse and a skiff, and to fly a shuttle. From Abiatha, the old chanter who tended the belfry and the altar in the Chantry sanctum, I learned not only prayer but skepticism and that even priests have doubts. From his masters, the priors of the Holy Terran Chantry, I learned to guard those doubts for the heresy they were. And of course there was my mother, who told me stories: tales of Simeon the Red, Cid Arthur, and Kasia Soulier. Tales of Kharn Sagara. You laugh, but there is a magic in stories that cannot be ignored.

Those first few pages, the framing structure established by the fictional author in a later stage of life, read too much like rhetorical hogwash, so I moved onward to the actual beginning of the story. My original skepticism was a problem here, because I still wasn’t sure of the nature of what I was going to read, and whether or not I’d embrace it. I was looking for Dune, because that’s the kind of expectation set up by countless other reviews, but it was only some very vague, very superficial imitation. This book and Dune both start with a training duel and the presentation of some characters in the role of mentors, but whereas Dune is already, from the very beginning, thick with meaning and depth, here I could only find a similar shape but stripped entirely of that depth. The main character’s family deals with the production of an important resource, in Dune it’s the spice and all it implies, here it’s uranium. And, while fundamental in the scope of this economy, it’s just that. Fuel. There’s obviously nothing wrong about this whole set up, but the book itself explicitly evokes Dune in its initial motions, only to then trigger an upset because it only take what’s pointless and superficial, and none of its depth.

I was mentioning that training duel session because it exemplifies some issues I had directly with the prose and especially with the descriptive parts. The writer attention seems to wander aimlessly without order or logical sense. At some point during that duel it is mentioned that the walls or some window (here I’m quoting by memory, it’s not important to be accurate) started to vibrate, because some ship was landing outside. Since this detail was completely out of context, I immediately deduced this was some clever foreshadowing intended to signal the arrival of someone important whom we’d be going to meet in the next scene… But nope. It was just an anonymous ship landing without consequence.

Later in the book, but not by much, the main character is assaulted, in a scene that would have been quite dramatic but only in retrospective. The mind-focus constantly wanders off:

The next street I found wound up and to the right, its limestone-and-glass facades curving around and artfully grown over with grape vines, though it was the wrong time of year for them to bear fruit.

Then he gets mugged:

My breath was knocked from my body, and I struck the paving stones with a grunt, my long knife under me. My back ached, and it was all I could do to get my arms under me and rise to my knees.

And the mind goes:

Too-black hair fell into my face, and suddenly I understood the utility of Crispin’s shorter style.

He got attacked by some biker, so this description follows:

the primitive petroleum engine belching poison into the air.

And when you get assaulted with an imminent risk of death, where goes the mind?

Where he had gotten the thing – from some guild motor pool or back-alley deal – I never knew.

How is it relevant the provenience of a bike, and its owner, that we will never see again? And then:

The pipe also must have been what had struck me down. But it was the man’s face that caught my attention. The left nostril had been clipped, sliced up to the bone so that the thing gaped awfully in the light of the burning streetlamps. And on his forehead, text proclaimed the man’s crime in angry black letters: ASSAULT.

Call it subtle, will you? Again some pages later, but still in this first section of the book (chapter 12) the chapter starts with a paragraph dealing with a number of considerations about possible avenues to leave the planet. This paragraph ends and without any sort of transition it completely switches theme, resuming considerations about what happened in the last page of the previous chapter. It’s just a very jarring, complete shift from the previous paragraph. You’d expect to follow the train of thoughts, but instead you find yourself on completely different tracks. Along with some silly, convoluted lines that read like parodies:

I had hoped Kyra might share whatever childish hopes I had

I thought I was different. I had not thought that I could be no different.

I get what it means. These examples aren’t especially meaningful or especially bad, but I’m using them here to give some examples of the way I felt reading every single page. A sense of “wrongness” that permeates the prose. On goodreads I was documenting my reading progress and wrote “there are descriptions distracted by trivialities, at the wrong time. Dialogues have all wrong timing and content…” It was as if fighting with obsessive, intrusive thoughts the whole time. The density of the prose, the overwrought style didn’t give it a sense of depth and meaning, but of enhanced superficiality. Something constantly offbeat. But at the same time I also realized that a big problem wasn’t the writing, it was me. Because I was constantly dividing myself, and so distracting myself. I wasn’t simply reading, but I was “judging.” I was trying to read and at the same time observing myself in the act of reading. Constantly wondering and second-guessing if there was something wrong in the writing, or just me trying to pick up a fight with the book itself. I was caught in this overthinking and I couldn’t get away, I couldn’t ease into the book because of this constant internal split. Observing the act of observation, to catch what was wrong in it.

I certainty couldn’t go on like that for 600 pages, and I didn’t. I don’t know if the writing improved, or if I simply adapted and eased in. But the situation got better, very slowly but steady as if going through a regular sloped trajectory. But I still wasn’t in good terms with the book, at all. I knew from reviews to expect a “slow start”, and that it would get better around 200/250 pages, but when I got there, the book got actually worse for me. I started to get the idea that this wasn’t going to be a good experience in the end. But now I’m writing from the perspective of someone who read the whole book, and I know I have a rather positive opinion of it.

I’m trying to avoid spoilers, but in this case what’s written in the back cover still has to take place when you have read HALF the book. I mentioned that, around page 250, I got to the point where most other readers say the story “picks up”, but since this part corresponds to when the main character enters the gladiator arenas, I expected that this is where the story settled. And I couldn’t care less of reading about some pointless battles written in the style completely devoid of tension. Thankfully none of that happens, even these scenes come and go in a few pages, and once again the scene shifts. At around this middle point of the book I got on peaceful terms with the prose, and I was alright with the nature of the story as well. The main character, while never quite endearing, became “readable”, as in making sense, including the constant sidetracks of thoughts. But more on this later.

The point is to wrap up this first part of the book and figure out what happened. In many cases I read people complaining about a “slow start” but I think the problem is the opposite: it’s way, way too fast. This apparent contradiction is obviously not one. The first part of the book, stretching over 200 pages, is constantly switching scenes. Not only the “circumstance” around the main character change, but also the surrounding cast of companion characters constantly shifts. Every time it’s a change of scenery and faces. Every time, characters that seemed important, richly described, get moved off the page never to reappear, and a brand new cast shows up to get a similar treatment. This creates a reading fatigue because why do I need to absorb all these names and details when these dudes are going to fall off the edge of fiction in the next ten or twenty pages? Why do I need to put effort absorbing a whole new set up, with the promise it won’t even last two chapters? What is truly important in this story? Where is it even going? It’s almost picaresque, but where the single episodes simply aren’t strong enough, interesting enough to hold up on their own. Too fast, too inconsequential, too random happenstances.

The problem of “nothing happens” is precisely that everything happens so fast that it’s emptied of any consequence. It’s all a blur (despite I was reading very slowly and attentively). This whole first chunk of the book is like a series of completely different short stories that are glued together, whose only common feature is of sharing the narrator. Each one of them could have been, potentially, its whole book. But there’s no time, it’s an ever changing of scenes. Now, I’m quite wary of deducing things that are impossible to deduce, but my best guess is that my own problem with the prose, and of the whole first section for both its structure and plot, could be caused by excessive editing. I get the feel that maybe Ruocchio tinkered with the beginning of this book for a very long time. That entire sections, and then line by line, the text has been cut and pasted, moved around, reassembled. And the final result of that process has been one that gives it that fragmented feel overall. Of things that have been compressed, robbing them of the natural flow of the prose and writer intention. Of a thought that moves in harmony with its environment, rather than being pulled in every direction at once. It’s as if an original draft was filtered over and over and over, until only nonsensical fragments remained.

Thankfully, the structure eases, along with the writing, plot, characters and everything else. Not with the gladiator arena, but at some slightly later point, 300 pages in, almost perfectly the halfway point in the book. Once again most characters are brushed off, and they continue to churn until the very end of the book, to be honest, but this process overall settles progressively. Characters linger, more and more. The story finds some vague unifying theme. It all starts to breathe a little more. And have space to do so rather than constantly pulling the rug under one’s feet.

The good parts of this book, in this second half, are probably ones that don’t sound that good when explained. The Dune-like introduction to the setting is “what if Paul Atreides was born into House Harkonnes, and was more like Anakin Skywalker instead?” That part doesn’t last long, as already mentioned with the constant context shift. So, again, the problem wasn’t in the potential of the idea, but that not much is done with it. Same for all the following fragments. But at the same time what surfaces is this quirky main character that you cannot quite pinpoint. I wasn’t sure while reading, and am still not sure whether this effect is deliberate or not, as a writer intent. Hadrian is not “likeable.” He’s stuck up, kind of annoying. His narrating voice is slightly pedantic. Is Ruocchio trying to write a nuanced, off-putting character that doesn’t want to be an immediate fan favorite, or he’s trying but failing? The strong morality at the base of the character is meant as a wide arc that span the whole series, but is certainly intended to ground the character in a positive way. At the beginning is like the character comes out good and likeable because of the contrast of how despicable everyone around him is. But in the end it’s quirkiness of the narrating voice that holds the interest.

When his “love interest” arrives on the scene, Ruocchio casts such an immense spotlight that I couldn’t avoid thinking “oh please, can you try LESS?” So corny and cliche to become immediately cringe.

Valka’s laugh was a deep, musical sound that escaped her chest from somewhere near her heart. It was not the laugh of some churlish courtier, trained to demure and girlish precision. No, she laughed like a storm cloud, like the sea. And she had broken on my grim demeanor like a wave against the sea wall at Devil’s Rest.

Enough to break the book right at that point. But the thing is that this character (Valka) gets written immediately as typical and cliche, but she’s not a typical love interest. The description is, but not the character. It’s as if Valka too is slightly askew, colliding with what you would expect, so creating a contrast that stays interesting through the rest of the book.

The main character, Hadrian, Valka, but also more of the cast around them, being oddballs makes them interesting enough to follow and sustain the story. As the book moves into more of its second half, as the plot settles and finds a common theme, it starts signaling its own identity. There is a wide ranging mystery to solve, but it’s faint, more like an intellectual puzzle than immediate necessity. All this, on the whole, gives the shape of the story an even more introvert angle. A personal intellectual obsession rather than action driven or plot driven. The story slows down but improves. I’m trying to avoid spoilers but as I describe the latter part of the book even the mention of the tone, of what is or isn’t there is a GIANT SPOILER, so beware. In the last 100 pages the plot and overall mystery picks up and gets more into focus. This is what then defines the whole book in retrospective, because to be honest there’s very little “space opera” here. We are in space only for an handful of pages, entirely irrelevant, and the whole of the story takes place in a series of different environments, but amount to a limited series of rooms, in the end. It’s very much “boots on the ground”, but also gives it its “bottom up” perspective. From the personal to the wider ranging. What truly defines the whole book and the characters is an anthropological perspective. An human perspective, rather than a worldly one. For all the attempts by Ruocchio at claiming aliens as truly alien, they are just as alien as actors wearing suits and elaborate make-up in Star Trek, and not entirely unintended. And so the theme becomes an insight into human nature, and does this fairly well the more it engages with this core and leaves behind its inconsequential conflict of other interests.

I saw a fragment of a video where Ruocchio was criticizing something about Herbert, as if claiming that his story would be a reaction of something that Herbert didn’t execute quite correctly. I didn’t watch further because I didn’t want to abstract the themes out of the book, before reading first. But this helped to set all the wrong expectations. Important writers are there TO BE challenged. That’s fine. Herbert deals with philosophy and even metaphysics, competently and upfront. This book doesn’t even reach 5%, or even 2% of the profundity of Dune, but it doesn’t even try. The challenger didn’t even show up to the fight. As with Bakker, you can complain about something you wanted to be in the book, that isn’t there, or you can simply comment on what the book tries to be. In this case Ruocchio hasn’t failed at all, simply because he didn’t try going there. This one has none of the metaphysical depth of Dune, nor it tries to. We’ll see what comes after.

But the philosophy that is there feels more like quotations you give at parties to look smart, rather than real philosophy. More evocative poetry and courtesies than philosophy. Including some magical thinking that probably shows too much of Ruocchio’s own magical beliefs:

We live in stories, and in stories, we are subject to phenomena beyond the mechanisms of space and time. Fear and love, death and wrath and wisdom – these are as much parts of our universe as light and gravity. The ancients called them gods, for we are their creatures, shaped by their winds. Sift the sands of every world and sort the dust of space between them, and you will find not one atom of fear, nor gram of love nor dram of hatred.

Just… no. Not the textbook dualism again. There are two languages, but one world.

This sets the tone. As long the philosophy stays anthropological, then it’s fine. The human angle is well done, without going too far. The interest Hadrian takes in the other forms of life and their expression is endearing and sounds true compared to the rest. And so that part of the book becomes more interesting and stronger. On one hand I knew the book being so incredibly popular that I expected somehow it would become just heroic action scenes in the arena. Something to gain that type of hype. And instead it grew… quiet (forgive the pun if you are in the know.) At page 354, we are well past the halfway point, chapter 52 is titled “little talks”, and it’s not even euphemism. The story slows down while it gains more of an introspective, searching angle. A scientific inquiry matched with more nuanced characters and interaction.

The last 100 pages, as I said, bring more the theme into focus, but always matching this intellectual angle of careful examination. I didn’t know if to expect surprises and plot twists from the end (spoilers again), but there were none. The plot languidly follows the already projected course, almost effortlessly. I got soured by the torture scenes, but that’s more my own sensibility (I can go through Bakker’s horrors without worry, this part annoyed me, instead, because of its more clinical execution). I didn’t quite like the final part, because the writer wants the tension high even if there’s no reason for it. Reading through it was a bit eye rolling because it felt quite forced. But the ending itself is executed very well. It does its job: it closes the whole chapter represented by this book, even giving substance to what would be otherwise an inconsequential sequence of unrelated stories, and sets the course for something entirely new, as the context for the following. A significant shift of context that creates the curiosity to go immediately read about it. (though the immediate mention of an unnecessary, upcoming adversary felt out of place and again too cliche)

If for most of the book we have fragments of scenes, and characters that come on the stage only to disappear again, creating a constant renegotiation of premises and so a growing distrust at putting the effort to learn about all of that, it’s Hadrian himself that strings these otherwise unrelated episodes into something that feels cohesive. His internal landscape is the link. The “magic” (see above) of the story. It’s never necessary to the plot or the story, but Hadrian constantly keeps bringing up those characters and events that would be otherwise forgotten. They don’t become relevant again, but Hadrian clings to those memories so stubbornly that he manages to cement their importance even for the reader. Hadrian’s own focus gives importance to what isn’t, FORCES that attention from the reader, going even against the flow of the story. This kind of BACKWARDS momentum is what I consider the main quality of the whole book. That it doesn’t give up about what came before. That it never fully moves on.

One of the most interesting character is Anais. Like Valka she’s painted as a complete cliche. A naive, airhead princess. And she’s never given a chance. Yet, like Valka, she doesn’t quite fit her mold, and her COMPLETE absence from the last part of the book gives her substance. Because it would take immense courage and maturity to simply step back. Her absence grants her the upper path. Hadrian flight from her is the flight of a coward.

While reading this book I had to course-correct a lot of my expectations, both negative and positive. In the end my response to the book is very positive, and going back I’d have far less scruples about whether engaging or not, whether it would be worthwhile or not. The whole point was to read something outside of my perimeter, so it wouldn’t make sense to use my usual yardstick. This is also very easy to recommend to other readers, in a similar way of Sanderson for fantasy, but better than Sanderson as a more grounded and thoughtful read. For me, a lot depends on where this story goes. Already for this book, the whole trajectory is able to lift all that came before, not incredibly so, but in a noticeable way. It cast a better light even on the first half that I criticized up here. Hadrian held it up as a whole. But I’m not sure Ruocchio could go and write effortlessly something entirely different. In this I join the majority of other reviewers, the strength of this writing seems directly bound to a very specific style of character, rather than the result of a writer and his skills, seems more the result of Ruocchio himself. It’s a sort of narrowing cage, that is up to Ruocchio to defy. But I’m also sure he’s already well aware of all this. And he doesn’t need to prove anything, same as all of us.

(This “review” really didn’t need to be this long… I’m exhausted once again.)

4 Comments

I wrote the following paragraph as part of the review, but I decided to cut it in the end. It doesn’t fit anywhere and it’s not meaningful enough.

But still it says something about what I thought, so I decided to put it here:

There’s a little nag that stays: is maybe Ruocchio a bit too young a writer, and so still not acquired that complete cynical angle that paints all things differently? He’s maybe just writing about some heavy themes and implications, but space opera for “kids”? (relatively, I mean) This is completely irrelevant as a judgment, but I do think there’s a certain legitimacy in the feel of some slight immaturity about this whole first book. Not felt as a burden, but just a faint, looming shadow over the whole. We’ll see if deliberately intended (it does represent a naive introduction to a world), or just the product of contingencies about the writer (I do suspect it’s some of the latter, though).

“I had hoped Kyra might share whatever childish hopes I had”

“I thought I was different. I had not thought that I could be no different.”

Oh, wow. I really don’t know how the editor did not catch that.

I am surprised how much you liked the book in the end. I hope the following books improve upon the foundation.

Because I don’t even think those are really errors.

It’s a bit like a more readable Severian (Gene Wolfe), at some point you have to embrace the quirkiness of the writing and the character.

токарный чпу станок [url=http://tokarnyi-stanok-s-chpu.ru]http://tokarnyi-stanok-s-chpu.ru[/url]

One Trackback/Pingback

[…] the other side of this duality of blogs I wrote a review of Ruocchio’s first book and mentioned in there that I had started casually watching the “booktuber” island of […]