Just a passing mention while I keep getting distracted by everything else.

Here’s a link to some sort of blog article by New York Times Bestselling author Jessica Clare, of “The Succubus Diaries”. She explains why you should write short books:

http://jillmyles.com/2009/06/09/a-rant-on-word-count/

Bloated word count costs your publisher money. I’m sorry, but there it is. You can fit three fat books on a shelf where six slimmer ones might fit. You get paid the same for both. Would you rather sell three or six? Would you rather B&N or Borders order 3 copies of your book or six? What about Wal-Mart?

So, after having dutifully pointed you to the sane life advices, let’s indulge with the more satisfying blowing up of approved literary behaviors. I was saying, I’m constantly sidetracked, so that’s why reading progress never progresses. I did manage to finish the 550k mammoth of “Parallel Stories” (some quick comments here). That was a while ago. Two recent interesting book purchases have been these two:

– The Runaway Soul by Harold Brodkey

– The Complete Novels by Flann O’Brien

The first one is interesting because, as you notice, it’s not even in print since it was such a smashing success, so I got an used copy for a low price (and almost pristine hardcover, very nice). It took the writer 32 years to write that ambitious scaffolding of a book, and that’s after becoming a big name praised by the likes of Harold Bloom. The relatively lean wikipedia entry is quite enough to unearth paradox and contradiction: “the one necessary American narrative work of this century” – “If he’s ever able to solve his publishing problems, he’ll be seen as one of the great writers of his day.” The genesis of the book also shows the level of hype: “The work became something of an object of desire for editors; it was moved among publishing houses for what were rumored to be ever-increasing advances, advertised as a forthcoming title (Party of Animals) in book catalogs, expanded and ceaselessly revised, until its publication seemed an event longer awaited than anything without theological implications. In 1983 the Saturday Review referred to “A Party of Animals” as “now reportedly comprising 4,000 pages and announced as forthcoming ‘next year’ every year since 1973.”

I like boundless, unreasonable ambition. I like to observe even when it goes hand to hand with failure. There are various levels, from Ed Wood to, apparently, Harold Brodkey.

This is mythology in the making. Mythology of a writer as an abstract entity. The Paris Review interview with the author is a sarcasm-filled article that I found interesting from the beginning to the end. The interview is so candidly naive and makes you understand (?) the ennui and weariness of the pampered life as a bourgeois writer. Such an hard, heroic life. It’s so bursting with narcissism that you can easily go from contempt to pity. But beside that, there’s also plenty of actual good stuff. Actual work. Detached from the real world, but nonetheless with its own, aloft value. I was more and more curious about reading the this book, more and more curious about reading what he actually had to say.

When New York magazine came out with my picture on the cover a couple of years ago, I would be walking down the street and people would pass me, and then I would see the same people again, a minute later; they’d circled around to see the cover in life. And I would think, What do I do? Should I smile? Do I really like this? What’s the etiquette here? I think I did like it, but I’m not sure.

There’s a Yiddish word, yenta, for the sort of person who nags you all the time. Frank O’Hara was a yenta. I wasn’t someone he publicized, but twice a year he would confront me and tell me that I was a great writer, a great artist, a great thinker, whatever, and that I was just hiding. And he would say that this was despicable. He would say that the work was fantastic, that it had influenced him, but unfortunately (he would say), I was a middle-class drag, not serious about becoming famous and influencing the world. William Maxwell said many of the same things to me. I practiced evasion until I was forty.

Of being an honest, wholehearted, fame-spurred writer. A sucker. A writer—and eaten up by it. Then, when I was forty, I gave up. I stopped being evasive. I clumsily wanted to be known. An eaten man. I think—and I have some evidence from when I was a teacher—that most people who try to write can succeed but don’t want to; I would argue that psychologically they would rather daydream about creating texts and being recognized while having real lives—they would rather do that than publish, I think.

I got this idea of being a writer someday. Then life, despair, became things I could study, like arithmetic or geometry, or Time magazine. It wasn’t that everything was okay, but that they became handleable in a certain sense.

Because of the peculiar circumstances of my life I had to find a way to get along with my conscious mind, or I really couldn’t exist, and one way to do that was to start thinking about my life as a story, or something to be interpreted or examined. I didn’t think I was going to write about my childhood, but I thought I would write about something that would make things that were obscure to me clear . . . by setting up one of those tremendous structures of suspense in fiction.

It may be the realest and trickiest and most violent thing you can do—to be published. The “silly Charybdis”—a childhood joke—of the insoluble thing of the choice proposed: to live or to publish.

At first one has two lives. One is the literary life in New York, The New Yorker, people who’ve read what you’ve written; and the other is the life you have with your old friends. In those days I was more athletic than I am now; I’d go and play tennis, or go canoeing with old friends . . . but after a while they don’t trust you. At the job I had, the people there didn’t trust me. They’d say, You’re going to write about it, you’re going to write about it. I’m not going to write about it—but no one believes you. Then they think, “Is he laughing at me?” And suddenly you’re more at home with strangers, with other writers, than with the people you’ve been at home with for years.

There were maybe four or five years of the double life of being a writer and still being a person. Then by, say, 1957, before First Love came out, I was really fed up. Between the two I really thought I’d rather be a person than a writer. Starting in 1959 I began the slow retreat into reclusiveness.

Instead I did it my way, which didn’t work, and by the time it was apparent it didn’t work I was exhausted and frightened, seriously frightened by what I had found out about myself as a writer . . . the ways my writing will and won’t meet me halfway. The ways I have to behave or the writing will stay dead.

There are about nine hundred million aphorisms about writing that are true, and one of them comes from Bill Maxwell—all short stories should be written in a sitting. As I understood it, that meant that you could spend weeks, months, years writing drafts, outlines, notes, sections, but sooner or later you ought to take all that and sit down and write a draft in a sitting, in a single flight—which might take days or weeks but without interruptions—so that the broad elements and the nuances cohere, certain echoes, certain resonances fit together, and there is real motion in the narrative—not a false motion linguistically grafted onto the story. Words have a strangely changeable, contingent kind of meaning, and as T. S. Eliot said in one of his famous essays, the music of language carries more of the realer meaning than the literal meaning of words does. A shift in the mind, in the mood, and you lose control of that music. Often, in a text you can see the fracture points where the music was lost and then regained or not. If not, the piece stays flat. A final draft has always been a little bit like a dramatic performance, but a performance that can sometimes last for several days with very little sleep; what sleep there is is troubled. The longest single sitting I can remember lasted for six days. I had to have Ellen stand by the desk from time to time I was so mixed up as to where I was, what was real. She would tell me what time of day it was; her voice was how I located myself.

Or you find a sentence, and there’s something good in it, but it’s mostly a lie as it stands; if you’ve been really corrupted you go with the lie for the sake of the part that’s okay; but if you’re lucky and obstinate about protecting your virtue as a writer, then you can try to correct the sentence, refine it, rescue the truer part, replace the crap. But it’s very nervous work.

the cruelest to bear is the beginning, the confrontation with the blank sheet of paper, where you have the chance to get up and turn your back on being a writer. You think, “I’ll quit, I’ll live a real life as a citizen; I’ll belong to the PTA and love my children. And have a country house.”

I don’t know that I can deal with publication. In this country, to be published, to become a figure—a Mailer, a Styron, a Roth—is really not worth it. They give far more than they get.

I’m bad at it, and that seems to attract interest. People seem to like to watch me falling on my face. I don’t know how to deal with it.

I worry still: Is what I do useful? Is it morally worthwhile? Is it of profit to the culture that I do it? And, selfishly, I wonder if this is the way I want to spent my life. Do I want to write the way I do? Yes and no. I’ve come to terms with it. I don’t ever remember a time when I couldn’t write fairly well.

I don’t know anybody else in my generation who’s been so constrained by considerations of getting published as I’ve been.

Oh God. Publishing is a miserable procedure. Most of the reviewers are probably okay but a number of them aren’t okay. I mean they don’t write or think very well. And the politics, the politics of doing favors, and of being favored are hard to handle

I met Joyce Carol Oates at a book party. She said that she really envied me my silence, my not having been commented on as much as she had been. I mean, she brings out about two books a year, so she probably gets reviewed by, what, thirty-five, fifty, a hundred reviewers? Maybe she only glances at around three or four, but just seeing the headlines, just seeing all those voices, opinions. And then there are all those other opinions that do matter to her. She said she was jealous of my not having my head filled with others’ comments, voices, opinions.

Even before Ashbery switched to Stevens there was in his writing this evasiveness, this sense that God was dead and meaning was impossible to come by

I think there’s an inside and an outside to a sentence, and to a sequence of sentences. The inside is what you think, what you think you’re saying; the outside is what somebody else thinks you’re saying, and about you saying it. Editors and critics always feel they possess the inside—I don’t know why.

You imagine the space, and then create the voice to fill it.

But this novel becoming a legendary literary failure isn’t the whole picture, because, as the tide turns, it seems Brodkey managed to trigger only contempt to a level that makes you wonder if it isn’t a tad too much even for literary criticism… When he contracted AIDS the illness was the only thing he could write about, but even in the face of stark death he didn’t earn any compassion from the same literary establishment that praised and pampered him all his life: “a matter of manipulative hucksterism, of mendacious self-propaganda and cruel assertion of artistic privilege, whereby death is made a matter of public relations.”

Notice that I found out about Harold Brodkey because I was reading an interview with Peter Nadas, instead.

the ones usually referred to in this context are Henry Miller or Harold Brodkey, where there is no pornography and no kitsch. What Miller is most interested in is what happens physically between two people, while Brodkey is intrigued by how you can transform making love into a deeply religious and benign act, how, if at all, you can give pleasure to a tremendously beautiful girl who happens to be incapable of enjoyment. As such a story was written by an American, of course he finds out that you can.

And Peter Nadas own vagaries are equally aloft and interesting:

I could not close giving the impression that I was completely clear about the meaning of things. Maybe there is no such meaning. I am clear about the meaning of some things, and—I’m sorry, but I refuse to deny, in pure modesty—there are things I know a lot about. But in other cases I may be completely in the dark about the meaning. I don’t believe there are complete philosophical systems that have decided for me whether or not the world is accessible to our understanding—whether understanding is a process or a divine gift that we can receive ready-made, and all we have to do is go to church every Sunday morning or every Friday evening. So the novel could end only with that special state that is neither sad nor desperate, neither absurd nor realistic, the state you’re in—it’s actually lovely in its own way—when you’re not clear about the meaning of things and you’re completely lost as to the ultimate meaning of things. Which is to say, man is not a completed being.

The prose floats from scene to scene, often returning to an earlier situation but from a different perspective, gradually something else occurs. Associations are made. Narratives are linked.

The phone in an apartment begins ringing on page 35, but isn’t picked up until page 59… and it has rung only about ten times.

“Literary experimention” brought me to look up the other one, Flann O’Brien, that has the name hints, is a flamboyant writer that I’ve never heard about but that apparently is one of the very Big Names. I’ve only read 20-30 pages and I still have no idea about what I’m reading, but for now it fits in the same mental drawer of Vonnegut.

…But. September is a great month, and all you see above was not what I wanted to write about, because my purpose was instead to point at two books, coming out, guess what, next September!

And now maybe you see the link? Because these two upcoming books are ALSO literary impossibilities. Negative spaces of literature where failure (of communication) meets ambition.

The first, more mainstream book is, finally, “Jerusalem” by Alan Moore. Hyped as a 1 million word book, it turns out it’s a bit more moderate:

“I was determined not to have a publishing house editor near this book”

“Not like Lord of the Rings, it’s not a trilogy, it’s one book of enormous length.”

“The one I’m doing at the moment is based upon Lucia Joyce, James Joyce’s daughter, who spent the last 30 years of her life in St Andrews Hospital, the mental institution next door to the school I used to attend. I’ve got this story about Lucia wandering through the madhouse grounds. She’s also coming unstuck in space and time a little bit. She’s wandering in her own mind. I decided to write this in an approximation of her Dad’s language.”

“We’re suddenly following a gang of dead children as they tunnel about through time in a kind of fourth-dimensional afterlife”

“It’s been reported that it’s more than a million words, which it isn’t. I think my daughter Leah, who was touchingly proud when I told her that I’d finished the first draft, must have thought that I’d said it was a million, but no, it’s a pathetic 615,000. So it’s little more than a pamphlet, really.”

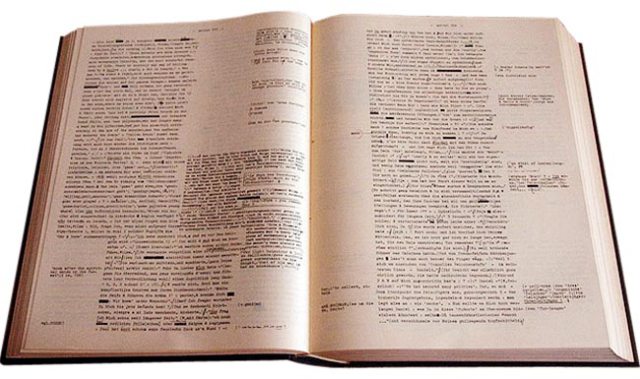

The second is just the physical manifestation of literary excess. Firstly in price: $70. And secondly in size: 1496 pages. But that pagecount might not even say the whole story, as this is an old book, released 46 years ago, and the pictures I’ve seen of the original German edition show something truly HUGE even in format, and with a page layout that can challenge Danielewski. The fact it’s been translated in English (and that it exists as a thing) is science fiction.

And here’s how it looked in manuscript form:

Zettel’s Bottom (and if you glance at the publisher, you can easily make the connection that shows how I found it, from Flann O’Brien to this).

Give it to me right now.

But if you think this is all too literary aloft I also have to confess I’ve ordered yesterday two other books. Outlander by Diana Gabaldon, after having spent a few hours on youtube watching interviews (1, 2 and bewildering enthusiastic review by intended audience), and Illuminae, that for some reason came ahead in my wishlist of Danielewski own literary excess: The Familiar series. I already have the first volume, even if it’s still in TBR pile, and it’s the second one I’ll have to order at some point, but for now Illuminae won my curiosity first, and I don’t need to write more about it since that book is already all over the place and praised in its intended circles.